Читать книгу The Dutch Maiden - Marente De Moor - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

1

You might say von Bötticher was disfigured, but after a week I no longer noticed his scar. That is how quickly a person grows accustomed to outward flaws. Even the hideously deformed can be lucky in love if they find someone who, at first sight, cares nothing for symmetry. Yet most people have a peculiar tendency to fly in the face of nature and divide things into two halves, insisting one should mirror the other.

Egon von Bötticher was handsome. It was his scar that was ugly: a careless wound, inflicted by a blunt weapon in an unsteady hand. No one had warned me, so his first impression was of a startled girl. I was eighteen and dressed far too warmly when I stepped onto the platform at the end of my first journey to another country. A train trip from Maastricht to Aachen, blink and you’re halfway there. My father had waved me off at the station. I can still see him standing beneath the window of my carriage looking surprisingly small and thin, columns of steam rising behind him. He gave an odd little jump when the stationmaster signalled for the brakes to be released with two blows of the hammer. Alongside us, red wagons from the mines rolled past, followed by trucks packed with lowing cattle, and in the midst of all this din my father shrank steadily into the distance, until he disappeared around the bend.

Up and leave, no questions asked. My departure was announced one evening after dinner, in a monologue that scarcely left room to breathe. The man was an old friend, had once been a good friend and was still a good maître. Bon. Besides, we had to face facts. We both knew I had to seize this opportunity to achieve something in sport, or would I rather go into domestic service? Well then, see it as a holiday, a few weeks of fencing in the beautiful Rhineland.

Forty kilometres separated the two railway stations, twenty years separated the two friends. On the platform at Aachen, von Bötticher was looking the other way. He knew I would come to him; that’s the kind of man he was. And sure enough, I understood that the suntanned giant sporting a cream-coloured homburg had to be him. Instead of a suit to match the hat, he wore a worsted polo shirt and what I took to be sailor’s trousers, the type with a wide waistband. The height of fashion. And there was I, the daughter, in a patched pinafore. He turned to face me and I backed away. The gnarled flesh of his torn cheek was still pink, though it had paled with the passing of the years. I think my shocked expression must have bored him, a reaction he had encountered all too often. His eyes drifted down to my breasts and I clasped my locket to cover what my pinafore was already doing an excellent job of concealing.

‘Is that all?’

He meant my luggage. He kneaded my fencing bag to feel how many weapons it contained. I was left to carry my own suitcase. The romantic image I had cherished before our meeting was fading fast.

It was an image conjured up by a blurred snapshot from our family album. Two men, one earnest, the other out of focus. Below the photograph was a date: January 1915.

‘That’s me,’ my father had said of the earnest man. Pointing at the other figure, little more than a smudge in an unbuttoned military overcoat and a fur hat, he said, ‘That is your maître.’

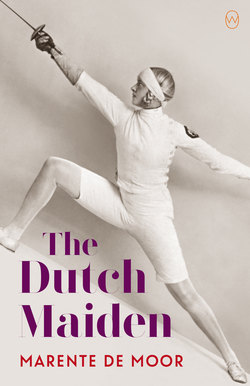

My friends thought the photograph was divine. Girls my age were all too eager to sketch in that blur of a face. He was sturdy and he was gallant, that was what mattered, and he had a country estate for me to swan around on. Surely this was a Hollywood ending waiting to happen? Yet all I saw was a worn-out man without a weapon. Instead of Gary Cooper or Clark Gable gazing down from my bedroom walls, I had the Nadi brothers staring at each other. A unique photograph, one I have never seen since: Olympic heroes Aldo and Nedo, both right-handed, saluting before a bout. It’s not a pose in which fencers are often photographed: facing one another in the same stance, exactly four metres apart, bodies staunchly upright, holding their blades in front of their unmasked faces. It looks as if they are sizing each other up along the steel of their weapons, but as a rule this pre-match ritual never lasts long. Not as long as it used to in the days when a duellist stared into his opponent’s eyes and took one last look at life.

It was War and Peace that first gave Herr Egon von Bötticher a face. I had pressed him between its pages as a bookmark. When I opened the book, his features evaded me just as he had tried to evade the camera’s lens, but as I read on they began to take shape. The haze of his blurred immortalization had robbed him of his pride. His fur hat was really a tricorne, golden epaulettes adorned his shoulders and a red-sheathed sabre hung at his left hip. I knew all this for certain. During my train journey I tried to read on quickly but I was distracted by a leering passenger who averted his eyes whenever I looked up. Every few sentences I would feel the heat of his gaze taking in my body through the compartment window and I read on even faster, skipping entire passages to arrive at the point where I wanted to be: the kiss between Bolkonsky and Natasha. My timing was perfect: I reached it just as we entered the tunnel. The passenger had vanished. I tucked the photograph away. I did not need a face, I would recognize my Bolkonsky among thousands. On that late summer’s day in 1936, he was the most distinguished of all the men at Aachen station. But on closer inspection he turned out to be a disfigured cad who let me heave my own suitcase into the car.

‘Has your father explained the purpose of your visit?’ he asked.

‘Yes, sir.’

Only he hadn’t. I had no idea what von Bötticher was talking about. My purpose was to become a better fencer, but my father knew the maître from a dim and distant past that would not remain so for long. He was German, an aristocrat with a country estate by the name of Raeren. At these words, my mother had begun to sob and shake her head. We had expected no better of her. The parish priest had warned her about the Nazis and their ill-treatment of Catholics. My father told her not to get herself into such a state. As for me, I barely gave these things a second thought. Nazis meant nothing to me. Von Bötticher, on the other hand, was inescapable. Without braking once, he drove me out of town over dirt roads and around hairpin bends. His knuckles slammed into my leg whenever he changed gear and his knee, sticking out to the right of the steering wheel, would have been nudging mine had I not inclined my legs toward the door of the cabriolet. He did not dress like a man his age, his sandals fastened around his ankles with a cord. My father, never one to shy away from a Gallicism, would have dubbed him a pigeon.

‘We’re here.’ It was the third sentence he had fired in my direction after a drive of at least an hour. Pulling up outside the walls of Raeren, he braked so abruptly that I shot out of my seat. He slammed the car door behind him and tore up to the gate, muttering as it groaned open, then jumped back in the car, screeched into the drive, and got out again to bang the gate behind us. It occurred to me that I would not be venturing outside these walls any time soon. Among the fading chestnut trees that lined the drive, my first glimpse of the place was the old roof turret, which was used as a pigeon loft. It would be a week before I was able to sleep through their cooing and the patter of their claws. And once that week had passed, I would be kept awake by matters far more disquieting.

Opposing mirrors reflect themselves in one other, a succession of images that become ever smaller and less distinct yet never cancel each other out. Certain memories exist in this state too, for ever bound to the first impression in which an older memory is contained. At the turn of the year, I had seen a film called The Old Dark House. I am tempted to say I recognized Raeren from the film, though it was only a passing resemblance. Even then I knew that I would always remember Raeren as the mansion where Boris Karloff had walked the floors. In my mind’s eye, its mirrors would always be cracked, its curtains flapping from open windows, the ivy around its front door stone-dead.