Читать книгу The Dutch Maiden - Marente De Moor - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

4

On my first night at Raeren, the pigeons found their way into my room. I dreamed of wrinkled claws walking all over me and a fat-necked grey bird trying to peck a birthmark from my throat. Stifled by the heat, I had left the balcony doors ajar and now I was too frightened to get up and close them. The birds seemed to be everywhere, scratching about the room. A preening silhouette was perched on the chair. The flapping curtain only let in fitful streaks of moonlight and, too tired to look for the light switch, I pulled the covers up to my chin. The second I woke up in the morning, the stink of the birds hit my nostrils: there were creamy splatters on the carpet and down floated through the air when I threw off the covers. The balcony looked like a battlefield. The pigeons had strutted around in their own droppings and seemed to have lost half their plumage as they wandered in and out. What had they been after? Now the roof was eerily silent.

‘A proper disgrace,’ said Leni when she came to tell me breakfast was ready. ‘Pigeon shit contains all kinds of germs. It can give you pneumonia, I read it in Die Woche. I’ll ask Heinzi to fit a screen. Or maybe we could furnish a room on the next floor down.’ She took the water jug from my washbasin and sloshed some of its contents over the balcony. In the end she had to fetch a scrubbing brush from the hall. Feet planted wide, she went at it, hunched and cursing. ‘The filth I’ve had to clean up today! It’s more than my job’s worth. What does he think we are, muck collectors? Oh, it’s a far cry from the biscuit factory.’

She was going to be a while yet, so I would have to find the kitchen on my own. Downstairs to the entrance hall, the door to the right of the mirror, all the way to the end of passage and down the steps at the end. I couldn’t miss it. No need to worry, the master was in the very best of spirits. He had been out for a walk, shot a young hare and was making breakfast himself. Oh yes, and she was to let me know that he was looking forward to my company. I felt the blood rise to my cheeks. This gallant invitation had ushered Bolkonsky back on stage. I pinned up my hair, straightened my back and off I went to meet him, doing my best to sweep silently down the creaking stairs. As soon as I set foot in the kitchen my expectations were shattered. Instead of sitting at the head of a table decked with white linen, von Bötticher was standing with his back to me kneading a lump of minced meat over by the sink.

It seems to me now that I spent all my young life daydreaming. The dedication I devoted to my fantasies made this a tiring habit. There was never enough time to see them through and, picking up the thread when I next had a moment to myself, I was confronted with all manner of imperfections. Even castles in the air needed cleaning, and there was always the risk of some young wench stealing away your beloved or an old harpy ruining your picture-perfect romance with her interfering ways. Besides, what exactly did a prince do all day? It could easily take me a good hour to iron out the wrinkles. My daydreams kept me awake at night and I lived with some stories for years, layering detail upon detail, down to the trim of the sleeves of my bridal gown. Only girls daydream with such dogged determination, of that I am sure. All young souls idealize the future, but it takes a girl to idealize the present along with it.

There he stood, von Bötticher, not Bolkonsky, in a long shirt, his wide sleeves rolled up to his elbows. Without his homburg, I noticed his hair was already turning grey. He was only a few years younger than my father. How long would it take for that fact to sink in? Imagination is more stubborn than reality—ask any madman who experiences moments of clarity. An illusion will always steal back onto the scene as soon as the original is out of sight, like a lover stepping out of a wardrobe and every bit as alluring. Even though von Bötticher tarnished his ideal image time and again, I had dreamed up enough to keep me going for nights on end. He turned his good cheek toward me and nodded as if he knew what I was thinking. He did not ask me whether I had slept well. It was a matter of indifference to him.

‘Where’s Leni?’

‘Cleaning up pigeon mess in my room.’

Von Bötticher pretended not to hear. He took white plugs of ground bacon fat from the mincer, pushed them into the stuffing and added an immoderate glug of brandy. These were unfamiliar smells. My mother spiked her stews with vinegar, as tradition dictated. Wine wasn’t something to be poured into a pot but something we drank once a year. Spirits never made it past the front door. Our next-door neighbour had once slipped me a slug of bitters during a snowball fight in the street, passing it off as apple juice—his idea of a lark. That morning, the maître’s kitchen must have smelled of the ingredients for a pie: bacon fat, cognac, a hunk of marbled boar meat, calf’s liver, kidneys, pickled mushrooms, and the egg pastry rising under a tea towel on the windowsill. The scent of the countryside poured in through the open window: vegetables sprouting in the kitchen garden and the clover on which the cows were grazing. The same clover was in the stomach of the hare that had just been shot. It lay limp-eared on the table, ready to be hung by its hind legs, which had been bound together with twine. In a few days’ time, its innards would be rinsed out and the smells released would drive every animal in the house to distraction. For now, it smelled of the sand in its fur and the grass between its toes—as did Gustav, still alive and well and hopping around under the table. That overgrown specimen didn’t give a damn about anything, least of all what was going on above his head. Though well-mannered enough to deposit his droppings in a neat pile in the corner, he sank his teeth into every piece of furniture he came across, shook his head, balanced on his outsized feet and washed his ears with his front paws. It was one surprise after another. Von Bötticher gave Gustav a piece of bacon, which disappeared little by little between his grinding jaws.

‘There’s something you didn’t know, eh? Rabbits eat anything. Even meat,’ said von Bötticher. ‘Just like cows chew out dead animals in search of minerals. Ever seen a cow with a dead rabbit in its mouth? They’ll happily gnaw a bone or two for the sake of calcium. It’s eat and be eaten in the natural world, no waste. Every last morsel gets consumed. The insects are first on the scene when an animal dies. Flies and mites can smell a hare like this one from miles away. Then birds of prey arrive and tear loose the skin, exposing the guts to foxes and badgers. But the rotting process alone will ensure that a corpse bursts open within a few days.’

He stroked the hare’s fur and sniffed his hand. ‘This one needs to be taken down to the cellar immediately. What on earth is keeping Leni?’

‘Are you planning to eat Gustav, too?’

‘Absolutely! With cowberries. Or smothered in cream, braised in Riesling and served with parsnips. Or wrapped in bacon and roasted after a night soaking in buttermilk. I’ll be sure to give him the attention he deserves. Ah Leni, at last!’

Leni was barely through the door when the toe of her boot connected with Gustav’s backside, to no discernible effect. ‘That monster has chewed the fringes off every carpet in the house. And unless my eyes deceive me, it’s produced a fresh pile of droppings. Sir, I ask you, I beg you on my aching knees: for God’s sake leave those animals of yours to roam around outdoors for a week or so. It will spare me all kinds of mess. The nights are still warm enough.’

‘And where would that leave me? How is a lonely man like myself to find warmth and companionship?’

Leni spread her arms wide. ‘And lonely you’ll remain while you continue to lock away your lady guests in the pigeon loft!’

Irked, von Bötticher tossed the dead hare into her open arms. ‘Here, woman. Take this down to the cellar and quick.’

Heinz came into the kitchen and sat down to wait while von Bötticher cut thin slices of sausage. This was clearly a morning ritual. The lord of the manor boiled eggs, removed a young cheese from a bowl of water, served cream with a small basket of berries on the vine, and put a plaited loaf on the table. His manservant did not lift a finger, and when his wife returned he pulled back her chair and together they prayed in silence. Through half-closed eyes, I watched von Bötticher stare unashamedly at their knitted brows. I think he took pleasure in the fact that the first sight to greet them after their moment with God would be that mutilated mug of his. Once grace had been said, he made sure we filled our stomachs with the food from his table, as if we were stray dogs. He himself ate next to nothing. When the dishes were all but empty, he solemnly broke the silence to address a practical matter. ‘Well, Janna,’ he said on that first morning, ‘have you brought me anything? Something from your father perhaps?’

Leni’s eyes were ablaze in an instant, while her husband went on chewing steadily. He was all too familiar with the consequences of speaking out of turn. Besides, what was the harm in a letter? I put my knife down on my plate.

‘An envelope, maître. I’m sorry. I wanted to give it to you straight away but you didn’t want to be disturbed.’

‘An envelope, of course. Yet another letter. Well, let’s be having it.’

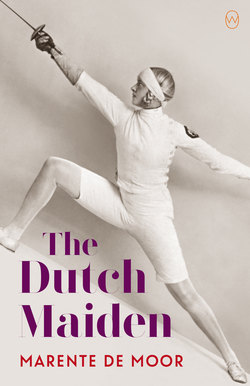

Von Bötticher dispatched me with a gesture an adult might make to a child who has been hesitantly holding up a drawing. I obeyed in a heartbeat. Back up the stairs I headed, in leaps and bounds, swinging around the pillars. I was childish, it’s true. Girls today are worldly-wise, independent, but in my youth we were simply passed from one sheltering wing to another. The only condition was that we in turn should have a caring disposition; it was not a condition I met. I much preferred being taken care of, so I could continue my playful, sheltered existence. Despite the inevitable physical transformation, I had no intention of becoming a woman. Not that I was a tomboy or a wild child or anything of the sort, it was more that I preferred things to stay as they were. It was an annoyance when I began to develop breasts at fifteen. Those bumps swelling under my nipples had nothing to do with me and I was seized by a curious melancholy that was a long time in passing. Helene Mayer took no extra measures to protect her breasts during her matches, and so neither would I. With that kind of padding under your jacket you are asking to be hit square in the target area. Admitting the possibility of a hit is a compliment to your opponent and refusing to do so made my parries stronger, especially quarte and sixte. A hit to the chest during a fencing bout left me sick to my stomach. I had no desire to feel those milk glands, those maternal appendages. I would never become a mother. Nor would Helene. It could be no coincidence that my idol bore the name of the most beautiful of all the Greek goddesses, the protectress of young virgins, she who had been abducted and overpowered. We were girls of Sparta, who battled on so we would never have to grow up, but we were passionate just the same. In my daydreams I increasingly became the object of desire. At night my painstakingly composed allegories were thrust aside by impatient, unbridled phantoms who left me panting and satisfied. Phantoms I had been unable to capture, just as they had been unable to capture me.

Fencers are often a little childish: playing at musketeers, wearing their hair long, swigging wine from the bottle, stamping around in their boots and pounding on tabletops. Such antics end on the piste, where deadly seriousness is the order of the day. Even von Bötticher was playful in his way, though his imagination was directed at animals. He taught them to behave like humans and when he succeeded he was happy as a sandboy. The task of opening the letter fell to Gustav. This was pure showmanship, of course: look how clever my rabbit is and how little store I set by this epistle from your father. His bunny nibbled neatly along the edge with mechanical dedication, even giving a little tug when he arrived at the corner so the resulting sliver of envelope could be detached and devoured. A letter opener could not have done a better job. Von Bötticher slipped his hand between the cardboard sides, pulled out the letter and began to read. For three full pages, I hardly dared draw breath. I stared intently at his eyes, as if my father’s words would be reflected in them, but they darted from line to line and, as Leni had feared, began to smoulder furiously.

‘I’ll spare you the embarrassment of reading it aloud. You’re his daughter and it’s not my place to shatter the image a daughter is apparently supposed to have of her father. I have said enough already.’ He folded the letter and stuffed it back in the envelope, which still had more to divulge.

‘And what else do we have here?’

It was a yellowed sheet of paper, an illustration. I grew dizzy with curiosity but von Bötticher walked over to the sink, placed the envelope between the pages of a cookery book that was thick as a fist and slammed it shut.

‘Very well. We shall see who is right,’ he said scornfully. ‘I expect you in the fencing hall for your first lesson in half an hour.’

The fencing hall had once been a ballroom. The parquet in the middle had been worn by a century in which dances traced circles. The floorboards, on which laced-up satin boots once followed the heavier tread of army officers, now only bore the weight of footsteps that advanced and retired, still following but never in the round. Three pistes had been drawn in black paint, delimiting the strictest of choreographies: fourteen metres long and two metres wide, two adjoining triangles pointing out from the centre toward the on-guard lines at a distance of two metres on either side; it was a further three metres to the warning line for sabreurs and épée fencers, one weapon’s length beyond came the warning line for foil fencers, and then it was back another metre, and not a single pace more, to reach the end line. The net curtains billowing in front of half-open terrace doors were the sole reminder of rustling tulle ballgowns. It was warm. I tugged at the collar of my quilted jacket and caught sight of myself in the large mirror: the swordswoman. My face and my hands looked brown against the white of my suit, which my mother had given a quick soak in a dolly blue. I took up my favourite foil, pulled on my glove, and stood heels together, feet apart. Salute. At that moment, von Bötticher entered the hall. It was there, in the mirror, that I first noticed his limp.

‘Salute yourself, as well you might. For now, you will be your only opponent. A formidable foe, as every fencer knows.’

‘When will the other students be arriving?’

‘You will have to make do with two sabre-wielding boys. Don’t worry, I am planning to have them practise with the foil again. You know the type: young hotheads incapable of placing a decent riposte but all too happy to wave a big sword around. Speed and endurance, the mainstays of youth—they have nothing more to offer. They were due to arrive last week, but two days ago I received a telegram from their mother. There appears to be some kind of problem. You will have to be patient. Until then, let’s see whether you are as good a fencer as your father claims.’

He came closer, dragging his leg irritably. ‘My gait is not always this laboured. My leg is playing up today. Show me your weapon.’

I grasped the blade of my foil and proudly offered him the grip. One wrong word about this weapon and all would be lost. Von Bötticher kneaded the leather, stretched his arm, peered along the length of the blade, let the foil spin between thumb and forefinger, kneaded the grip again, weaved his wrist this way and that, and then nodded. ‘Very well, now show me you are worthy of such a weapon. Stellung!’

‘Unarmed?’

Before I knew what was happening, he struck me full on the chest. ‘Ninny! When you hear “Stellung” you take up your position, understood? Or must I resort to French? Stellung!’

I assumed the on-guard position, my hand thrust out before me, gloved and empty.

‘What do you call this?’

He tapped my left hand, which I held in mid-air behind me. ‘Relax those fingers! Keep them loose. You’re not hailing a carriage!’

He then turned his scrutiny to the distance between my feet and kicked the back of my heel, which perhaps deviated one per cent from the line he had in mind.

‘Tsk … Ausfall!’

He left me standing in the lunge position till my thigh muscles began to tremble, correcting my stance down to the last millimetre. I knew he could bark another command at me any moment. ‘Stellung!’

I shot back into position. The maître gave me my weapon and slapped his chest. ‘Now, show me a splendid lunge.’

‘But you are not wearing a jacket.’

He fastened a single button, a tiny shell, half a centimetre across. ‘This button is your target. If I were you I’d worry about the impression your lunge makes on me, not the indentation your weapon leaves behind.’

I was almost beginning to miss Louis back in Maastricht. He may not have been a bona fide maître but at least I could count on his admiration, stamping for joy when I landed a hit. I was Louis’s best pupil and he would much rather have seen me bound for an academy in Paris than the retreat of some obscure military man in Germany. Those officer types understood nothing about women’s fencing. When von Bötticher packed it in after fifteen minutes, I began to fear Louis was right. Having examined my body from the soles of my feet to the tips of my fingers, he declared it to be a reasonable apparatus, limber, enough of a basis to work from, but my ability to react, my speed, my tactical skill—in short everything that had won me prizes back in Maastricht—were of no interest to him for the moment. He had other matters to attend to, and I was left to fence against my reflection. I hoped he would look on in secret from the terrace. The curtains flapped, the door banged shut. In the mirror I took in my formidable opponent. She made me feel uncertain, and uncertainty is a fatal flaw for a fencer. There she stood, too short in stature, brandishing a weapon of which she might not even be worthy. She was not ugly, some even said she was pretty, there’s no accounting for taste. I was not to my own taste. It was the Aryan race that made my heart beat faster. It was not something you could admit to ten years on, but I truly loved blond, blue-eyed young men who were hardy as cabbages in a frozen field. There had been boys who fell for my skin, the colour of young walnuts, but I brushed their attentions aside. In my daydreams I looked entirely different. It was a girl at the fencing club in Maastricht who had stated the cold, hard facts. ‘You look far prettier in the mirror!’ she had exclaimed, adding hastily, ‘I mean … well, you know what I mean, don’t you?’ The damage was done, I had been knocked off-balance for ever. What the Janna in the mirror needed was a mask, then all would be well. Masked I could face down any opponent, including that jealous cow at the club. At Raeren, the masks hung from a rack on the wall. One of them was a snug fit, though there was no one to see me. Von Bötticher’s angry voice drifted up from the garden. He was giving Heinz what for, something about dead fish and a pond. I hung up the mask, lay down my weapon and slunk out of the room.

Back in the kitchen it didn’t take me long to find what I was looking for. The book lay in the middle of the chopping block: Gastrosophy. A Breviary for the Palate and the Spirit. Many of its pages seemed to consist of coloured-in photographs. Fish dishes shaded in pastels. A roast piglet with its trotters in a helping of lentils. Crimson landscapes of meat stretched across the centre pages with a butcher’s knife held in a pale hand to point the way: how to chop the backbone of a lamb, how to bone a leg of pork, how to slice the tendons from a fillet of beef. It reminded me of the illustrations that hung in my father’s surgery, a dissected human body with muscles, organs and bones exposed. As a child I refused to believe there could be a skull hidden behind my face. The butcher’s pale hand showed how to cleave shoulder from foreleg. The envelope had been removed from the book.