Читать книгу The Dutch Maiden - Marente De Moor - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

2

The front door looked like a coffin lid. I was being melodramatic, of course, but when von Bötticher left me standing there while he went back to fetch something from the car, the house seemed to radiate a loneliness that resonated with my own. Minutes passed. I stared at the black paint, the tarnished knocker and the silver nails. Then the door swung open and as if to complete the scene a deathly-pale little man appeared on the threshold. He said nothing, a daguerreotype from a time when people were still in awe of their photographic perpetuation: rooted to the spot, eyes fixed on the horizon, face drained of colour.

‘Heinz! What kept you?’ von Bötticher shouted from a distance. ‘The gate needs oiling. Leave it any longer and I’ll never get it shut. Where is Leni?’

The little man braced himself, took the suitcase from my hands and cleared his throat. ‘In bed, sir. No need to worry. She’s promised to be up and about by lunchtime.’

‘This is Janna, the new pupil I told you about. Remember?’

‘I can make a pot of tea,’ said Heinz, without so much as a glance in my direction.

‘Take the girl upstairs. I do not wish to be disturbed today, for once.’ Then suddenly with a smile, ‘Except by you two!’

He was talking to the St Bernard and another smaller dog that had been waiting in the hall, bottoms quivering with excitement. This was something at least. Though I had never had a pet dog, there was still a reassuring familiarity about them. Lacking words, animals simply cannot be strangers. The St Bernard let me stroke it briefly before bounding into the garden to greet its master, stamping playfully on the ground with both front paws at once. I was left alone with Heinz, who had something to tell me. ‘We do not have a telephone.’ He thrust a pointed finger in the direction of the outside world. ‘The lines run north along the main road and don’t reach this side. There’s already a telephone pole on every corner of the village, but the master doesn’t see the use. We don’t have many visitors. That’s something you should know. Other than the butcher and the students, no one comes to call.’

The clock in the hall had stopped. Later I would discover that Raeren was full of clocks that no longer ticked and cupboards that contained nothing at all. It was as if everything had been put there for appearances’ sake. The interior offered two contrasting moods: rustic and faded chic. Everyday life was confined to the smoky kitchen, where the beams were hung with game hooks, pots and kettles, all in frequent use, and where a rough-hewn dining table invited you to rest your elbows on its knotted surface. The grand section of the house was steeped in a silence that was amplified by the slightest movement. Even the hint of a footstep would trigger a salvo of creaks and groans from the wooden thresholds, floorboards and furniture, noises so unwelcome that these were rooms where dust hung in the air instead of smoke.

Von Bötticher strode into the hall, the dogs trailing in his wake. ‘Take the girl up to the attic room and bring these two and Gustav to my study.’

‘I can’t get hold of Gustav, sir.’

‘Try luring him with a biscuit. Kaninchen sind verrückt danach.’

‘Rabbits are mad about them.’ Was that really what he’d said? My knowledge of German came courtesy of the summers I had spent at my aunt’s in Kerkrade. There we spoke of Prussians, not Germans. My aunt ran a stall that sold coffee beans in a town where the border between the two countries ran down the middle of the street. Our side was Nieuwstraat and across the road was Neustrasse. Her customers stood with their feet in Germany while their hands counted out coins in the Netherlands. There were no language barriers to be crossed. Everyone spoke the dialect of the Ripuarian Franks, whose drawling caravan of words had left deep tracks across the Rhineland in the fifth century.

I was five years old and carrying a cured ham in my apron to deliver to a Prussian who had asked for a sjink. ‘Come straight back, you hear!’ I remember the bustle of the crowd, the ham growing heavier and heavier. Two drunken miners pointed at my apron and burst out laughing. ‘Bit young to have a bun in the oven … ’ I lost my way. Three hours later, they found me in a back garden on the German side of the street, ham and all. The lady of the house saw me playing there with a serious expression on my face. What else is a five-year-old to do under the circumstances? She called to me and I ran into her arms. Though she was German, she spoke the same Kerkrade slang as my aunt, in the same seemingly indignant tone. ‘Hey, ma li’l angel … and who might you be?’ Since that first foray across the border I returned home from every summer holiday with a Rhineland accent, much to the horror of my mother, who set about replacing all my Germanisms with the Gallicisms of Maastricht.

Kaninchen sind verrückt danach. I rolled the words around my mouth as I followed Heinz upstairs to the attic. The staircase bore our weight like an old beast of burden, groaning as it took us from landing to landing. On each one he halted, put down my suitcase for a moment and then took hold of the next banister before creaking on, step by step.

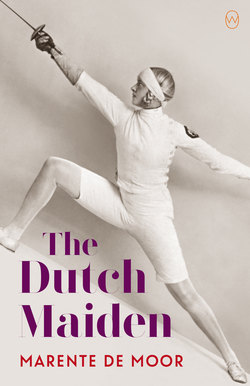

‘Have you been fencing long?’

‘Since the Olympiad.’

Heinz turned and frowned at me. The Berlin Olympics had ended only weeks before.

‘I mean since the 1928 Games. In Amsterdam.’

‘Ah, I see. You should have seen our Games. The Olympiad to beat them all. There was a torch relay for the Olympic flame. They had invented a new electronic system for the fencers to tell them when a point had been scored.’

I searched for daylight on every floor, but all I saw were hallways lined with closed doors. The higher we climbed, the more ominous the atmosphere became. Not a bad smell exactly, just the stale air of unused rooms. Once this house had been built in preparation for a life, enough life to fill ten rooms, a kitchen, and a ballroom. The staircase had borne the weight of a young master of the house as he carried his bride upstairs. Children had slid down the banister. But the decades wore on, bringing evenings when someone climbed the stairs never to come down alive. A room was kept dark, a hush descended on one floor and then the next, till silence reached the bottom stair. This house had been empty for a long time; I could feel it. Sometimes a house never recovers from such a blow, a fresh coat of paint can only give it the air of a jilted lover who feels all the more disconsolate for having dolled herself up. It’s better left as it is, with its cracks and smears, the greasy imprint of a hand that reached out in haste on the way from the dinner table to the ballroom, the loose handle of a slammed door. The wallpaper on the attic floor was in tatters. Had a cat been locked away up there? A child? The heat was stifling.

‘Has von Bötticher lived here all his life?’

‘No.’ Heinz put my suitcase down in front of a small door and sorted through his bunch of keys. ‘He hails from Köningsberg. After the war he moved to Frankfurt, and then he came here. But these are matters that do not concern you.’

The room was more pleasant than I had expected, sunny with a small balcony. Olive-green wallpaper, a high three-quarter bed, a small paraffin heater, and a desk with an inkpot. The sound of birds cooing was very close. Heinz opened the doors to the balcony and two pigeons made a U-turn in mid-air.

‘I have other things to attend to,’ he said, backing out of the room. ‘There is nothing more I can do for you at present. My wife will bring you something to eat later. You’ll find water at the end of the hall if you wish to freshen up.’

He clattered down the stairs, leaving me behind with the birds. I started to unpack my suitcase. The linen cupboard was lined with dust and I sacrificed a sock to clean it out. I had to fill this room with my sorry caseful of possessions and fast, or things here would never turn out for the best. I flicked away a dried-up fly that had strayed witlessly onto the bedside table and perished there. War and Peace took its place. I put my fencing bag in the corner, hung my coat on the hook. The letter was at the bottom of my case, sealed in a large envelope made of stiff cardboard. Nothing but the name of the addressee on the front: Herr Egon von Bötticher, a name like a clip around the ear. I stepped into the sunlight, but the cardboard was giving nothing away.

I considered it, of course I did. If I had read the letter that day, perhaps things might have been different. But I knew from experience that the discovery is never worth all the trouble. The speculative excitement buzzing around your brain as you steam open an envelope soon fizzles out when you clap eyes on its contents. A handful of statements about someone else’s humdrum existence, what good are they to anyone? And then there’s the ordeal of resealing the envelope, the problem of torn edges, the anxiety and the shame. I laid the letter aside.

Muffled expletives drifted up from the garden. The shadow of a man edged across the lawn with what looked to be a ball on a leash, a ball that was refusing to roll. This turned out to be Heinz, with the biggest rabbit I had ever seen. I took a closer look—yes, it really was a rabbit. Its ears were enormous, as were its feet. It seemed incapable of steady progress and settled for the odd jump, backward or sideways. Heinz’s patience was clearly wearing thin and after taking a good look around, he gave the creature an almighty kick. Just as I was beginning to wonder whether anything in this house was normal, amenable or even remotely friendly, there was a knock at the door. I opened it and we both got a shock, the woman in the hall and I. No, it wasn’t her—her nose was wider than my aunt’s and her eyes were blue. But if she hadn’t been carrying a tray laden with food, I would have happily fallen into her arms. No matter what kind of woman she would turn out to be, at that moment I decided I liked her.

‘Hello dear, I’m Leni.’

She kicked the door shut behind her and put the tray down on the desk. I saw sausage rolls and dumplings sprinkled with icing sugar, but I didn’t dare touch anything. Leni took a chair and sat down at the window, leaning on her sturdy knees. She heaved a deep sigh.

‘So, here you are stuffed away in the attic like an old rag.’

‘It’s a nice room.’

‘Come now, it reeks of pigeon shit. The air up here’s enough to make you ill.’

‘I hadn’t noticed.’

‘Well, you’d better tuck in before you do.’

Her whole body shook when she laughed—cheeks, breasts, belly, the flesh on her forearms exposed by her rolled-up sleeves. If she hadn’t been sitting on them, her buttocks would likely have laughed along too. I started to eat.

‘The master’s an odd ’un, all right,’ she said bluntly. ‘No need to look at me like that. Like you haven’t already twigged. We’d been out of work for six seasons when he bought Raeren. We’d always worked at Lambertz, the biscuit factory. When we were laid off, we hoped Philips would open a factory in these parts. Rumours had been doing the rounds for five years but Heinz said there was no point in waiting any longer. Since then we’ve been in service with von Bötticher. An odd ’un, and no mistake.’

She stood up and began to whisper. ‘Have you seen his cheek? Taken knocks from all sides, he has. That scar is from two wounds, you know. One from the war and the other from them goings on he’s involved in. Take a good look next time you see him, he’s in a sorry state. Not to mention that leg of his!’

I burst out laughing and she looked at me as if she had been served a meal she hadn’t ordered. ‘You must admit, he’s not a pretty sight.’

‘I have a letter for him, from my father. Could you make sure he gets it?’

She frowned as she took hold of the envelope. ‘Quite a size. What’s it say?’

I shrugged. She placed the envelope back on the desk.

‘Wait a bit, that’s my advice. The letter your father sent a while back fairly upset him. He wasn’t himself for a time. One minute he was strutting around all pleased with himself, the next he was flying into a rage over nothing. Then came the telegram announcing your arrival, and that left him in a bit of a tizz, too. I don’t need to know the details. His bad temper’s his own business, even if Heinzi and I are the ones who bear the brunt of it. If you want to get off on the right foot, I’d keep this to yourself for now.’

Her voice changed key in these final sentences, took a dive from high to low, and I realized it was more than just her appearance that made me feel at home with this woman. She spoke the indignant Frankish border dialect I knew so well. If anything were to happen to me at Raeren, I knew I would cling to her like a lost child. Together we stared at the strokes of my father’s pen, the careless hand in which a doctor scrawls his suspicions on a letter of referral, as if illegibility might soften the blow.