Читать книгу The Dutch Maiden - Marente De Moor - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

5

Everything stayed within the grounds at Raeren. Only the clematis scaled the wall, beyond which an occasional farmer’s cart could be heard crunching along the path. By the sound of things the world outside did not have much to offer. The time might come when I would have to climb those walls in a fit of fear and panic. I wasn’t ruling that out, but during those first few days there was still so much to explore. In the orchard I had seen a little ladder leaning hopefully against a tree laden with hard green apples. The garden was more work than Heinz could handle. The rose arbours and flower beds were overrun with ivy, while the kitchen garden vegetables had taken on grotesque shapes and sizes. Abundance run riot.

Before Heinz had a chance to even consider these chores, he had to spend the entire morning behind the house, where the animals were kept. At six the horses were already kicking at the stable door, while the smaller livestock squealed in their pens. From the terrace I could watch him unseen, our gardener from the biscuit factory, cursing a creature behind a knee-high wooden fence. ‘Dirty little rotter. I’ll rub your nose in it. Just you wait, I’ll shove you right in.’ Unable to get hold of whatever was running around in there, rending the air with its rusty scream, he pulled loose his pitchfork and continued mucking out. What else was he to do? His eccentric master had more time for his animals than he did for his personnel but ignored the filth his menagerie produced in much the same way as teenage girls ignore their boyfriends’ pimples. Von Bötticher’s animal utopia was a lie from start to finish and no one knew this better than Heinz. It was he and no one else who stood there every morning up to his ankles in all that these noble creatures spilled out upon God’s green earth. ‘Lord preserve us! Don’t get me started …’

The cattle up on the slopes were the only livestock he did not have to tend. They belonged to a neighbouring farmer, a taciturn man orbited by a swarm of the same flies that buzzed around his animals. When the weather was warm, the cattle lay down with their legs tucked under them. If you approached them, you could hear the sloshing and gurgling in their massive bodies as they heaved themselves up, their inner workings going full tilt. They refused to be patted but were quite happy to wrap their pliable tongues around your feet and drool half-digested grass over your shoes. From one day to the next they would vanish. This meant the farmer had herded them off through the woods to let the grass grow back. It had been that way for years, no need to waste words explaining it.

Out on the terrace I ran my circuits, four lonely mornings in a row. This was part of a schedule the maître had drawn up and hung in the entrance hall. Seven o’clock: morning training session. Eight: personal hygiene. Half past eight: breakfast. Half past nine: a walk and instruction. One free hour after lunch, followed by an afternoon training session and domestic chores after six. During the week, the pupils—whoever they might be—were expected to spend the evening in their room. Leni had taken the schedule down off the wall and brought it to my room so I could copy it into my exercise book. She had no need of schedules, she said. From the second she opened her eyes in the morning till she closed them at night there was more than enough to keep her occupied. Once the downstairs rooms had been mopped, she had exactly one hour to attend to the bedrooms before she began to get hungry and it was time for breakfast. Schedules were for bosses and other layabouts. I needn’t think for a moment that Herr von Bötticher was the full shilling. An unhappy man, that’s what he was. Back when he had only just moved to Raeren and they had been taken into service, he had no routine whatsoever. When the moon was full he would stay up all night only to collapse into bed during the day, sick as a dog.

‘Don’t you believe me?’ she said. ‘He spent those first few days standing up, like he was afraid of the furniture. It wasn’t his, you see, it was here when he bought the place. All he brought with him was a few chests of books and weapons. Every time I looked he was on his feet, at the window, against the wall, in the garden, which was a complete jungle by the way … What you see now is all thanks to Heinzi. We’re the ones who got Raeren running like a normal household. Leni, my mother always used to say, when a person has no routine he’s done for. All that’s left of him is a sad little heap of need and suffering. And right she was.’

Starting another circuit, I picked up the pace. The wind carried the peal of bells from a distant village. Somewhere people were being called on to button up their children’s cardigans and send them out into the world. But the chiming soon stopped and left me alone with my heartbeat. All those discouraging sounds from within: blood pumping, joints creaking, lungs heaving. Saddled with a complaining body as his sole companion, every athlete feels lonely. I was about to stop when the doors to the fencing hall flew open. There stood the maître in an instructor’s jacket, black leather so stiff it made a straight line of the contour of his torso. He wore it well, I’ll give him that. Not like Louis, whose natural slouch made him look like an upturned beetle, arms flailing from his carapace.

‘Keep running, stay on your toes. Arms stretched as high as you can. Higher. Faster. Come on. Now continue on your heels, knees up, stay relaxed.’

After every exercise he looked at his watch. Next I had to take up my weapon, make thirty step-lunges over the length of the terrace and counter every attack he threw at me. ‘Clumsy! You have another fifteen minutes in which to redeem yourself.’

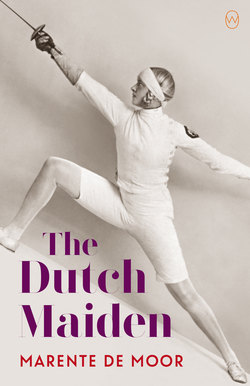

He tapped my behind with his foil. A frivolous act; a hit on the backside has nothing to do with fencing. For a foil fencer, the target area begins under the chin and ends in the crotch. That is all he has to work with, the body of a carelessly excavated Greek god. I shook my forearm loose, jogged on the spot, adopted the on-guard position, inclined my weapon against the ball of my thumb, fixed my eyes on the point of his foil and met his gaze. If only he had worn a mask, I am sure I could have stood my ground.

‘Now do you understand why I asked you yesterday whether you could fence against yourself?’ he asked, as he knocked my weapon away with a lightning-quick counter-parry. ‘I know your next move before you’ve even decided on it.’

I didn’t see the point of training in front of the mirror. As if it were possible to catch yourself off guard. A reflection corrects itself in a fraction of a second, but take the mirror away and errors creep back in like thieves under cover of darkness. I’ve heard fencing likened to playing chess at high speed. The outward spectacle is nothing compared to the forces at work behind the mask. Throw it off to see more clearly and you realize it’s your mind and not the mesh that’s obscuring your vision, speeding up your footwork or slowing it down. One moment everything is still clear: your opponent is standing there, well within range, ready to raise his weapon and step forward. But won’t he get too close? How could he still land a hit at that distance? Where’s the logic? It would make more sense if he … Too late! Too much thinking. Von Bötticher insisted there was no point in trusting your eyes, in wasting time passing images to your brain. There was something stronger, something you couldn’t quite put your finger on. A vague, melancholy memory of long-lost forces that growled in the pit of your stomach and rushed to your nose … or what was left of it. In animals, smell took pride of place, but in us humans it had sunk to the bottom of the brain. That’s what walking upright did for you. First see, then grab, we’d been doing it for millions of years. But what fencer had not been ambushed by euphoria as his weapon, seemingly of its own accord and without the least resistance, hit his opponent’s body in less than the blink of an eye?

‘A dog bites the hand that feeds him before he has a chance to regret it,’ said von Bötticher. ‘Just as animals smell their prey, you can sense an attack hanging in the air. The only question is: whose attack? Let emotion drive your fencing, only then will you know what speed is. Instinctive motivation works too. The sense of reward or punishment is swift as an arrow. Fear, pleasure, hunger, thirst: they all take the shortest route. Do you even want to hit me? Do I frighten or please you?’

I feigned an attack on his scarred cheek and then caught him full between the ribs. He staggered, quickly resumed his train of thought, limping as he advanced. ‘Fine. Bravo. You were riled and you attacked. But beware. Fencing on intuition does not mean you can simply forget your technique. First the patterns have to work their way under your skin.’

With both hands, he pulled on an imaginary set of reins. ‘Have you ever ridden a horse?’

I nodded and shook my head at the same time. My grandmother had an old carthorse with the kind of fuzzy grey coat that makes old animals so endearing. It tolerated my legs dangling at its sides but had no intention of being spurred on by them. Few experiences were as calming as those journeys from farmyard to farmyard, borne by a mute creature that had been clopping along for far longer than I had been drawing breath.

‘I’ll ask Leni to lay out some riding clothes for you,’ said von Bötticher. ‘Breakfast is in half an hour, after that I want to see you ride. No need to be frightened. I’ll give you the most docile horse and put her on the longe. You’ll learn a lot from it. Everything I have told you today will fall into place. Now off you go.’

Five nights I had spent at Raeren. The maître had already dispensed with formalities and my life lay entirely in his hands. My bed was under his roof and he was the one who determined when I had to attend to my ‘personal hygiene’: thirty minutes before I put his food in my mouth. Obediently, I stood at the attic window with my feet in a basin. Heinz had fitted a screen and on the other side of the mesh a wood pigeon was nodding off. It opened a beady yellow eye when I poured the water. On waking up, I had gone to the washroom, filled a jug with water and left it standing in the sun. Leni was adamant I should wash downstairs with warm water from the boiler, but that made me feel uneasy. I would rather be up here being leered at by a pigeon. My moment of triumph was enough to keep me warm. A shivering heat flowed down from my navel as I thought of the tip of my foil making firm contact with von Bötticher’s jacket. An immaculately executed feint below his weapon. He had wanted to maintain appearances, feign indifference, but one half of his face had refused to cooperate.

How long does the triumph of the crippled war veteran last? Six months at most. By then his mutilation no longer inspires admiration but pity, and a surfeit of pity becomes an irritant. When I was younger, a blind Belgian used to beg on Market Square; both his legs had been amputated. He accepted money from passers-by without so much as a word and you immediately understood that, however much you gave, it would never be enough. Here was a debt that would remain unsettled. When it became clear that every contact would be rebuffed by his empty eyes and bare stumps, people began avoiding him. He became a war monument no one had asked for in a country tired of looking on from the sidelines. True, those few cents could never weigh up against the millions of guilders the Netherlands had demanded from Belgium after the war for housing its refugees, while handing Kaiser Wilhelm a castle for his trouble. But everyone was relieved when the veteran disappeared from the square. About time, said Uncle Sjefke, good riddance. The war had been over for ten years and it was about time those Belgians stopped their whining. After all, everyone in Maastricht remembered those dodgy characters with plenty of money, those so-called refugees who drove up the rents in 1914 and undercut local workers by accepting low wages to top up their government handouts. For all we knew, that blind misery guts had been one of those ungrateful sods, always complaining about the food served up by their host family, one of those drunks who out of sheer boredom ended up back at the front playing the hero. And who’s to say he was a hero at all? He could just as easily have been a common smuggler who had crawled under the Wire of Death and survived the two-thousand-volt shock while his legs went up like charcoal. It wouldn’t have been the first time. My mother hissed between her teeth, there were children present, but Uncle Sjefke just snorted and crossed his arms. He had said his piece. He wasn’t planning to sympathize with anyone, no matter what. You had to watch out for sympathy, before you knew it people thought you owed them something.

I crouched down in the basin until my bottom touched the soft soap suds. Von Bötticher didn’t frighten me. Of course, he didn’t please me either, what did he take me for? I could try to pity him but pity is a worthless emotion for a fencer. Feel pity when you are ten points ahead and you can end up losing 15–10 as a result, only to have your opponent triumphantly pull the mask from his face without a trace of remorse and thank you cordially. But if pity was out, what else was there? I had to find a way out of this impasse. And now there was a riding lesson to cap it all. If half an hour of next to no personal hygiene wasn’t enough to strip me of my dignity, a spell on the back of a horse tethered to the longe held firmly in his hand was sure to do the trick. To start with, that docile horse of his was anything but. It was a brownish-grey Barb, one of those arrogant desert mares. Von Bötticher had fallen for the breed’s warlike reputation. ‘Many a battle has been won astride a Barb horse,’ he said as we walked out to the meadow. My heart sank into my hand-me-down riding boots, two sizes too big.

‘The Prophet Muhammad, King Richard II and Napoleon swore by them. Napoleon was forced to give up Marengo at Waterloo. That horse was already pushing thirty, but went on to gallop for the enemy for years to come. Even in death he was pressed into service: his hoof was a tobacco box on General Angerstein’s smoking stand.’

Von Bötticher only had to point and she trotted over to him. She wasn’t big, that was some consolation, but she took one sniff and turned her backside toward me.

‘Loubna, be good now,’ said von Bötticher in a sugary voice.

She pricked up her ears and leered at her owner with one eye. If a human being treated you that way you wouldn’t stand for it, but von Bötticher had all the patience in the world. ‘Come now.’

With a grand sweep of her tail, she relented at last. He laid his cheek against her head as he offered her the bit. Then he slid his fingers under the noseband to make sure it was loose enough and lowered the saddle onto her back with such circumspect precision that I began to wonder whether this young madam would deign to carry me at all. As he tightened the girth, I saw myself reflected in her eye. Embarrassed by my round, pasty face, I looked the other way.

‘Isn’t she a beauty?’

‘I don’t think she’s going to let me mount her.’

‘Never talk like that in the presence of a horse. You’ll ruin your relationship before you’ve even started.’

I burst out laughing, but von Bötticher was in earnest. ‘What did I tell you this morning? They understand everything. Even before your doubts become words, she has drawn her own conclusions.’

In that case it doesn’t matter what I say, I thought despondently. Perhaps I should just call the whole thing off? After all, there were plenty more unspoken doubts where that one had come from.

‘Around horses it’s a matter of acting,’ he continued. ‘Play a part, pretend you’re the finest horsewoman in all of Aachen, make something up.’

He could say what he liked, my imaginative powers had up and fled. The horse walked at the end of her rope and the rider stood in the sand with his legs apart. And there was I, the rag doll in the saddle, an afterthought. After four circuits I was ordered to tighten the reins and press my calves against Loubna’s flanks. Needless to say, she didn’t bat an eyelid. She wasn’t born yesterday.

‘Keep your legs still,’ said von Bötticher. ‘No need to spur her on. Just take her as she is.’

‘It doesn’t seem to be working.’

‘Don’t give up so easily. Focus on your posture, keep your breathing calm and steady. You are the finest horsewoman in Aachen and you’re about to trot. It’s your decision, and that’s final.’

Nothing happened. The horse remained singularly unimpressed. Von Bötticher tried to distract us with talk of the weather. True enough, it was a sweltering day. The trees stood motionless, the birds had been left speechless and sweat trickled from beneath my helmet—much too big for me, of course, just like the rest of my riding clobber. I felt like a simple-minded child treated to a ride around the circus ring while the audience look on with forced grins on their faces.

And then came a new sound. Loubna was first to hear it. The hum of an engine beyond the gates, growing steadily louder. Von Bötticher hastily rolled up the longe, unbuckled us and off he went.

‘No need to be afraid. You’re doing fine.’

He was talking to the horse. He couldn’t spare a word for me, not even the faintest of smiles. The hum continued. I shortened the reins, looked over my shoulder and saw von Bötticher duck under the fence with surprising suppleness. He broke into a run—well, more of a hop-skip-jump—as he headed down the drive. He pulled open the gate and in rolled a butter-yellow cabriolet. The gleam of the windscreen denied me a view of the driver. Once we had disappeared around the side of the house, I tried to spur Loubna on and she quickened her pace to an uneasy clip-clop. The sound of the engine died away and was replaced by a woman’s voice, birdlike. She stood next to the car. A platinum blonde in a veil and a cherry-red coat dress. Despite her high heels, she stood on tiptoe to kiss von Bötticher. Loubna tugged sharply at the reins.

‘Easy, girl,’ I whispered. ‘He’ll be back soon. He’ll always come back to you.’

We had already broken into a trot. I sat deeper in the saddle and tensed my calves. Von Bötticher said something that made the blonde laugh effusively as she circled the car. All this time two boys had been sitting inside. That’ll be them, I thought: the young sabreurs, the hot-headed swashbucklers. They sat motionless in the back seat while their mother chirped and twittered, wiggled her hips, lost her veil. Von Bötticher went down on his knees. That’s what veils were for, to bring men to their knees. He seemed very young all of a sudden. Why wasn’t he looking at us? Loubna lengthened her back, we were almost trotting on the spot. I hardly needed to do anything and when I relaxed the rocking motion continued of its own accord. Then Heinz came out of the house to park the car and Loubna was off like a shot. An immense power unfurled beneath me and I fought for some kind of grip as I was tossed like a frail boat on a tidal wave. I looked down in horror at the horse’s thrusting neck, the force that was whipping up the storm. The car’s engine sprang to life. Loubna thundered across the sandy enclosure, jumped sideways and thudded to a halt with four hooves at once. I lurched backward, clinging to whatever I could lay my hands on. Straightening up my riding helmet, I hoped no one would see us as I tried to recover from our breathtaking trot, but the horse began to whinny in loud fits and starts. Strolling arm in arm down the path, von Bötticher and the blonde stopped in their tracks. He looked at me with his twisted face. ‘Get off her, Janna. Take her to the pasture and wait for Heinz.’

I slid from Loubna’s back and led her away through the loose sand. Heinz turned the car around. The young sabreurs were still sitting in the back seat. I took a closer look and saw they were completely identical.