Читать книгу The Dutch Maiden - Marente De Moor - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

3

My father loved to jot things down. He always had a pencil or two concealed about his person to scribble notes in the margins of the day. Nothing but twin primes?! on the bill from the baker. Argumentum ad misericordiam in the newspaper. Flushing half a tank will suffice on the lavatory cistern. ‘Just a sec’ was a pet phrase of his, often uttered as he leaped to his feet and his mood brightened. Many of my father’s discoveries were preceded by the words ‘Just a sec’. He would set about repairing the radio and end up reinventing the ear trumpet. Or he would find a new Bryozoa fossil on Mount Saint Peter, one that on closer inspection turned out to be half of a fossil he knew well. A practitioner of non-monotonic logic, his corrections were primarily directed at himself, cacographic messages that steadily filled the house. An addendum was scribbled on the cistern: i.e. approx. two seconds. After all, from the outside it was impossible to tell when half a tank had been flushed. This was not nitpicking or penny-pinching. He had simply discovered that the cistern was too large for its purpose. He would spend entire evenings writing and crossing out in chaotic piles of thin exercise books. He didn’t even miss them when they suddenly vanished. ‘Another set of problems laid to rest,’ my mother would say as the pages lay smouldering in the hearth. One opinion on any given subject was enough to last her a lifetime. She formed them instantly, an advantage true believers have over scientists. What had those two ever seen in each another? My mother apparently took to piety after I was born. For an entire week she lay wide awake in the bed where she had given birth to me, insisting she would never have to sleep again because she was already dead. She felt no urge to suckle me and when they brought me to her she would fly into a panic, convinced her cadaverous state was contagious. Expressing her milk made her gag. ‘Can’t you smell it?’ she would yell at the astounded maternity nurse. ‘That milk has long since curdled!’ Eventually my aunt sent for the priest and he prayed my mother to sleep. ‘From that moment on,’ said my father, ‘I woke up next to a complete stranger who happened to be your mother.’

They had a dreadful marriage. Housemaids came and went, their departure always ushered in by my mother’s sobbing fits. As soon as I heard her lashing out, I knew another maid was on her way. Father was no stranger to histrionics either. On more than one occasion the neighbourhood was treated to the spectacle of him marching out of the house with a huge suitcase, swinging it so demonstratively through the air that anyone could see it was empty. It was all about the grand gesture: ‘Your mother and I are getting a divorce.’ In the end, my father packed me off to Aachen with the very same suitcase, but the first time he stood on the doorstep with it we took a walk together and he told me about the war.

In 1914, he had interrupted his studies at the Municipal University in Amsterdam and travelled south to serve with the Red Cross in the city of his birth. He made no claims to heroism. Taking care of the wounded provided him with a unique opportunity to gain practical experience and exempted him from mobilization. But before long the front had advanced so far south that the staff of the emergency hospitals in Maastricht soon found themselves bored to tears. Six months later my father was on the train back to Amsterdam. He resumed his studies and became a medical doctor, the highest possible achievement for a young man from his non-academic background. He would have liked nothing better than to study for his PhD, even though it involved sitting an extra state exam. But then I came along and a doctor’s house became available in the Wyck neighbourhood of Maastricht. The Spanish flu came and went, and after that traffic accidents provided him with most of his patients. In a city without traffic lights, the number of motor vehicles was doubling annually and everyone was making up the rules as they went along. Competition with trams and rival bus companies was fierce, and bus drivers resorted to recklessness to give them the edge. The horrific injuries he saw reminded my father of his wartime experiences. As a GP his sole responsibility was the patient’s long-term recovery. Mr Bonhomme came to grief under the wheels of a Studebaker owned by the Kerckhoffs brothers and drank away his phantom pain in the public house. My father went down to collect him when the landlord complained of the stink.

‘Daddy?’

‘Mmmm … ’

‘When will Mr Bonhomme’s leg grow back?’

‘It won’t. In fact, there’s every chance his other one will drop off.’

‘Jacques, please! Keep a civil tongue in your head.’

Without my mother around, I could well have become a very strange child indeed. She preserved the peace and quiet of the domestic routine. Not a day went by without my father dreaming up some new adventure. Off to the summer fair in Beek, making our own pottery in the Preekherengang, shutting Grandma’s goat up in her box-bed, scaring the wits out of unsuspecting citizens by jumping from behind the Helpoort and shouting ‘Boo!’ For Christmas he gave me a little monk that peed apple juice when you pressed his head.

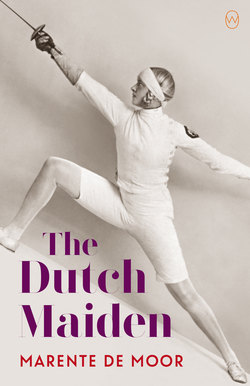

Sport did not interest him in the slightest. To this day I have no idea why he took me along to the Amsterdam Olympics. We stayed with an aunt—or at least I called her ‘Auntie’—who looked like Clara Bow. When we went out together, she slapped a cap on her mop of black hair and slotted one cigarette after another between her painted lips. My father was the picture of contentment as he strolled down the street with a lady on either arm. At a stall he treated us to Coca-Cola, tasting it first with a sceptical frown. What was it made of? Was it suitable for the ladies? Auntie Clara Bow insisted we go to see the fencing. My father thought this a very bad idea. The matches were not even held in the stadium but in a hall out front, where later all hell would break loose when a fight erupted between the spectators after a boxing match. The mood at the fencing was boisterous, too. See, said my father, combat sports are contagious. The spectators are infected by the aggression on display, proving this is not sport at all, simply an excuse for a common scrap. Auntie Clara Bow gave him a kiss and that was enough to bundle him through the entrance. She knew a remarkable athlete would be fencing that day: Helene Mayer, die blonde Hee as the Germans liked to call her. She had the allure of a film star, not unlike Auntie Clara Bow herself.

When I saw Helene Mayer for the first time, I was filled with the kind of adoration that can make a young girl queasy. I was ten, she was seventeen. Helene was a demigoddess, an untamed creature on the brink of womanhood who drove every full-grown woman from the fencing piste. This was only the second time women had competed at the Olympics. Who else was I supposed to model myself on? One of those biddies in bloomers who collapsed in an exhausted heap after running all of eight hundred metres? My father was a reluctant spectator, not only of the duel but of the fever taking possession of his daughter. He tried to talk sense into me, but to no avail. Whichever way you looked at it, surely these ladies would have been better off devoting their agility to a feminine pursuit—ballet, figure-skating or gymnastics? With their beautiful faces locked in those cage-like masks they screamed like animals when they were hit. Not cries of pain, those ridiculous outfits put paid to that, but cries of fear. Remember the day when Pontius the rooster escaped and Granny had to grab him by the legs? He screeched at the top of his little lungs, thinking his hour had come, and hadn’t we all felt so sorry for him? Well, that’s what it means to fear for your life. Pain doesn’t enter into it. It’s not a game. Perched on the very edge of my seat, I wasn’t listening to a word he said. The rules of the sport were a mystery to me. For the uninitiated, fencing matches are almost impossible to follow. Even the trained eye of the president falls short and he often has to rely on his judges to spot a hit. My gaze homed in on Helene Mayer, the victor. My father, as usual, only had eyes for the victim. He rambled on about the scaffold and vengeful mobs, but Helene had already drowned him out. Later she would loom large in the mesh of my mask as I prepared to lunge. No one could lunge like Helene. Every sinew, from her Achilles tendon to the tip of her weapon, conspired to conjure a lunge of at least three metres from a frame of 1 metre 78 and a blade of no more than 90 centimetres.

Before Father and I returned to Maastricht, Auntie Clara Bow braided my hair in the style of Helene. A middle parting and two pretzels over my ears, held in place by a bandeau. This kept your hair out of your face while allowing you to slip a fencing mask over your head. During her match against Olga Oelkers, Helene’s braids unravelled and her hair had fallen in golden strands over her shoulders. How could such a Teutonic force of nature lose? I was slender and a head shorter than she was—not exactly advantages for a fencer—and I was a brunette into the bargain. From that moment I resolved never to wear my hair any other way. My friends, obsessed with trimming each other’s pixie cuts on a monthly basis, thought I was being absurdly old-fashioned.

After my Olympic initiation, it was only a matter of time before my father gave into my moods. My reproaches were anything but loud, not a tear was shed, but for the best part of a year my anger was inescapable. I hid under the blankets with Dumas and self-baked biscuits for company. Every evening I disappeared upstairs with a baking tray, my books and my body increasing in size, the books growing fatter as the crumbs piled up between the pages. When my father finally summoned me for a chat, a small fencing jacket lay on his lap. ‘For my angry little musketeer.’ How typical of my doctorly father to put protective measures first and launch my fencing career with a jacket the colour of a plaster cast. He had heard of a small fencing school in the city, run by a young man called Louis. The fees were modest and beginners were allowed to hire their equipment. The maître had no official qualifications—to this day I have no idea how he came by his title—and he was having a fling with the cashier at the Palace Cinema.

I was allowed to borrow a rusty child’s foil. Everyone in Louis’s class fenced with rusty equipment, a good incentive: avoid being hit or end up with a reddish-brown mark on your pristine jacket, one that will never wash out. It wasn’t until my sixteenth birthday that I received my first adult foil. After class, when everyone else had gone home, Louis called me in and with a flourish produced a bewitching weapon. This was the real thing! The blade looked new to me, gleaming and flexible. Louis opened his fingers to reveal a ridged leather grip.

‘Take it.’

I took the foil from his grasp. My hand barely fitted around the grip, the end of which rested against the wildly pulsing artery in my wrist.

‘Not too big?’

‘No, it’s wonderful,’ I whispered.

‘It will mould itself to your palm before long. The steel is still very stiff, let me bend it for you a little.’

I looked on anxiously as he drew the weapon under the sole of his shoe to curve the blade.

‘That’s more like it. This foil is yours if your father will do something for me. It is important that you ask him immediately. It has to be done soon and requires complete discretion. From you too, so mum’s the word.’

My father frowned when I passed on the message. Of course, I immediately asked whether there was an abortion in the offing. Perhaps my maître’s bit of skirt down at the Palace had a little problem that needed attending to? My father was as dismissive as he was indignant. Who on earth had been planting notions like that in my head! And whatever Louis wanted in return, there was no call to assume that I was about to become the owner of a brand-new weapon. Such decisions were not Louis’s to take. Father had wanted to give me something else for my birthday, not a weapon for heaven’s sake. That was when I looked at my father, the pacifist and professional healer of wounds, and explained all. I told him a foil is not made to kill. It is a weapon to practise with, a sporting invention, never once used on the battlefield. The blade bends on impact to prevent fatal stab wounds and could never be used to sever limbs; besides, the rules of foil-fencing only permit hits to the trunk of the body. I told him it used to be called the fleuret, its point protected by a small leather cap that was said to resemble the bud of a flower. It was the first time my father took note of anything I had to say. With this weapon, my own dear foil, I became a grown-up.

My father idolized me, his only child, but my only idol was Helene Mayer. For years I dreamed of fencing against her. On the Olympic podium in Berlin the ‘strapping lass from the Rhineland’ had stood solemn as a statue in her high-necked fencing jacket and white flannel trousers, the swastika like a brooch below her left shoulder and her right arm extended in front of her. One step higher stood a Hungarian, gold medal around her neck and a little potted oak in her hands. By all accounts, making do with silver did not trouble Mayer much, but oh how she wept over that tree. She had so badly wanted a memento from German soil to take back to her new home: America. Only later did I discover that she was leaving Germany as I arrived. As if we had just missed each other. Perhaps it was for the best. Von Bötticher insisted that to be a good fencer you needed only one idol: yourself.