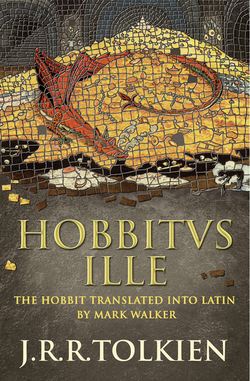

Читать книгу Hobbitus Ille: The Latin Hobbit - Mark Walker - Страница 4

ОглавлениеTRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

As a lifelong Tolkien fan and an ardent Latinist, translating The Hobbit into Latin has been a long-cherished ambition of mine. But I am aware that others might think of it as, at best, a rather whimsical endeavour (“You’re doing what?”, “The Hobbit – in Latin!”, “Who’s going to read that?!”). So perhaps I should begin by explaining why I think there are such good reasons for doing it that the only wonder is it had not been done sooner.

There is, as anyone who has taken the trouble to study Latin knows, a curious gap in the available reading material. On the one hand are simplified stories for classroom use, on the other the glories of high Latin literature – but remarkably little inbetween. What is there for the intermediate reader, who is tired of the textbook but not quite ready to grapple with the stately poetry of Virgil or the grand rhetoric of Cicero? What for the accomplished reader who wants to escape from Ancient Rome’s marbled halls from time to time? What for the reader who just wants to read Latin – the very idea! – for fun?

This is where the Latin Hobbit comes in. It is nothing more or less than a novel – but a novel now in Latin. Which is to say, it is a Latin text whose principal aim is to be read solely for the pleasure of reading, not one to be studied with the aid of copious editorial notes, or laboured over in order to glean hard-won quotations for an essay assignment. Reading for pleasure is a rare experience for Latinists, who, in my opinion, deserve to enjoy themselves as much as anyone else.

Happily, Tolkien’s immortal story lends itself to such a Latin translation: the sentences are generally short, the sense is always clear, the story is easy to follow. Tolkien’s perspicuous prose and the clarity of his exposition are a gift to any translator. But for the Latinist especially, The Hobbit has other recommendations. There are no telephones, computers, automobiles, or other such modern ephemera in Middle-earth (though Tolkien does mention a train once), so most of the action can be described using the vocabulary of a standard Latin dictionary. Tolkien writes with a sonorous dignity of expression that falls naturally into Latin cadences. And scattered generously throughout are an array of songs, which add delightful variety to the text.

As it turns out, the world of Bilbo Baggins is so vividly present to the imagination that it survives any artificiality imposed on it by translation into the language of Ancient Rome. Not that this version aspires to imitate the idiom of Roman writers anyway (a pointless exercise, in my opinion), but rather to present Tolkien’s words as faithfully and as comprehensibly as possible for the enjoyment of contemporary Latinists. This is not The Hobbit as if written for the Emperor Augustus; it is simply The Hobbit for anyone who has sufficient Latin grammar and a good dictionary.

There are, inevitably, some unfamiliar words. But I have not invented where Latin already has a term that at least approximates to Tolkien’s. So, for example, the fairy-like spirits of the Roman forests were dryades, which is sufficiently analogous to stand in for Tolkien’s elves; and if the Romans didn’t mean by nanus what Tolkien meant by dwarf, then we can say the same for the English word too. Hobbitus itself seemed a relatively obvious coinage, though I did puzzle over troll for quite some time. Trolls being creatures of Norse myth, none of the extant Latin terms quite seemed to fit – words like belua or monstrum were too general, and gigantes are clearly a separate race. But on the pattern of Gollum (a fortuitous neuter proper noun) I felt readers would not object to trollum (plural trolla). I had more trouble when Bilbo taunts the spiders with archaic ‘arachnid’ words like Attercop and Lob, for I not only needed something suitably scurrilous, but also something that would fit the verse metre; with a little effort, though, we might imagine that our Latin-speaking spiders are annoyed to be reminded of the fate of their mythical Greek ancestor, Arachne.

Most proper names remain easily recognisable and have simply been assigned a Latin termination and a declension – Bilbo is Bilbo, Bilbonis, Smaug is Smaug, Smaugis, and Gandalf is Gandalphus, Gandalphi – with the exception of names that are obviously descriptive; so, for example, Thorin’s surname becomes Scutumquerceum, and Bilbo’s bullish ancestor is Taurifremitor. The troll William’s nickname ‘Bill’ I have rendered as Rostrum – a little Latin pun, however execrable.

One of most enjoyable, as well as one of the most challenging, tasks was to render Tolkien’s many songs into Latin verse. Translating poetry from one language to another is necessarily more paraphrase than translation, so my first objective was to make my Latin verses true to the spirit, if not necessarily the letter, of Tolkien’s originals. To achieve this I had initially planned to use classical quantitative metres throughout – those formal edifices familiar to (and sometimes dreaded by) Latin students from classroom encounters with the Augustan poets. However, I soon realised this would not quite do. In the very first chapter, for example, the dwarves sing a solemn and ancient song, Far over the misty mountains cold, which readily lends itself to the weighty dignity of classical metre. But in the same chapter they break into an impromptu ditty about smashing poor Bilbo’s precious crockery, and this song, so it seemed to me, worked much better in rhythmic (and rhyming) form. When Gollum and Bilbo set each other riddles, these naturally take quantitative shape – this is, after all, an ancient game played since time immemorial – but when the goblins of the Misty Mountains sing to a marching beat, an ominous trochaic pulse best captures the rhythmic stamp of their feet. By contrast, the facetious elves of Rivendell express themselves in lilting iambics.

When I considered that many readers (unless they are musically inclined) will not previously have encountered rhythmic and rhyming Latin verse, I felt certain that this diversity of versification would impart a pleasing extra dimension to the book. Perhaps, after reading the Latin songs of dwarves and goblins here, you may be tempted to investigate some of the medieval verses that inspired them, the magisterial Dies Irae, for example, or the rumbunctious songs of the Carmina Burana. And if they inspire you to sing some Latin, so much the better.

Translating The Hobbit has been quite an adventure: exciting, fascinating, daunting, terrifying. All those, and more besides. When I began this project I shared the trepidation Bilbo felt on setting out; as the work progressed – seemingly with no end in sight – I had my own moments of despair in the darkness; but at last I rejoiced, as did Bilbo, in the satisfaction of bringing my own (literary) adventure to a conclusion: forsan et haec olim meminisse iuuabit.

All that remains is for me to extend my grateful thanks to David Brawn at HarperCollins for his faith in this book and in me, and to Mike Barry, the much-loved Head of Classics at Caldicott School, whose diligent proofreading of the early chapters saved me from some silly errors.

NOTA BENE

Unfamiliar or new words are marked with an asterisk (*) on their first occurrence and are glossed in the vocabulary at the end, where you will also find a list of proper names. The various verse metres are noted in a brief appendix. Spelling and orthography follow that of the Oxford Latin Dictionary, hence no distinction is made between vocalic and consonantal ‘i’ and ‘u’, and only proper names are capitalised. This has also been my primary (but not sole) reference for definitions and word use.

Mark Walker