Читать книгу An Intimate Wilderness - Norman Hallendy - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

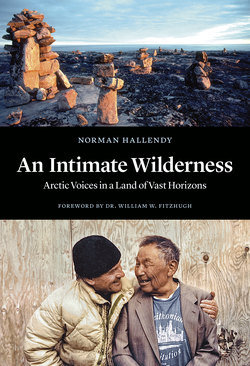

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

I am visited by a gentle sadness, for soon, like the geese, I will leave this place and fly south where summer lingers. Sekkinek, the sun, rises later each day while darkness arrives ever earlier. It is late August, a time when caribou shed the soft brown velvet from their antlers. Among the shards of summer scattered across the tundra, little grey spiders dart in and out of silken tunnels spun below the now pale gold leaves of Arctic willow. The women and children have picked the berries. White tufts of Arctic cotton have been carried away on the wind. Early morning frost has transformed the grey-green tundra into a vibrant landscape of red, orange, yellow, and gold. My footsteps on the dry lichen sound as if I am walking on crisp snow. Soon, another sound is heard, the moaning of the sea.

There is a place on a hill that opens to the vast horizon. Here we can sit and reminisce upon the sweet thoughts of life and wonder what lies beyond the horizon of our dreams. We can journey along a trail of memories to places so hauntingly beautiful they have to be seen to be believed, and to places so powerful that they have to be believed to be seen. I will shake the dust off my notes that tell of shamans and a world inhabited by spirits, and share with you all that was given me by men and women who lived at the very edge of existence in one of the most demanding places on Earth. They were people who had the genius of knowing how to create an entire material culture from skin, sinew, ivory, bone, stone, snow, and ice. They spoke to me of hardship, love, wonder, and all that defines the human spirit. Sargarittukuurgunga, a word as old as their culture, suggests travels across a land of vast horizons.

An Intimate Wilderness is an account spanning 45 years of journeys in Canada’s Arctic. Travelling in the company of Inuit elders, I learned about unganatuq nuna, the deep love of the land often expressed in spiritual terms. Other journeys were inward, across the last great wilderness within ourselves. There were times, when travelling on the sea ice to a distant camp, that we ached with cold, and there were times when we snuggled in an igloo beneath warm, soft caribou skins.

One of many notebooks filled with observations while in the field.

In a real sense, these journeys made it possible for me to live in two different worlds in a single lifetime. The familiar world was the one defined by the daily requirement to make a living. I spent my career in various capacities within the federal public service; eventually, I became a senior vice-president of one of Canada’s Crown corporations. I married, and my wife and I had two daughters, but our marriage suffered and ended while I worked gruelling twelve-hour days.

The other world was one in which I was free to traverse a place of endless wonder and where, for a brief time, I could become the person I had always wanted to be. Being in the company of elders exposed me in an intimate way to the land and to a way of life I had never known. They referred to themselves as “Inuit,” which means, simply, “the people.” From the very beginning, I saw myself as a student, continually seeking help from the Inuit elders to feed an insatiable curiosity. They helped me to understand why I was so moved by the landscape, the environment, and the insights of those who knew and experienced their surroundings so intimately. Whether living in a settlement or camp or travelling on the land, I assumed my correct place in the pecking order, which was inevitably at the bottom and in need of being “looked after.”

Over the years, I found myself becoming attached to certain individuals and families as their ilisaqtaulaurpunga innarnut, their student, relationships that lasted throughout our lives. I realize now that certain experiences gave coherence and a larger meaning to the individual things learned from day to day. The most important of these “learnings” was the attempt to understand what it meant to travel in one’s mind from a world believed to be filled with a multitude of spirits to an existence underlined by the promise of something better after death. So began a line of inquiry that will close at the end of my own earthly journey.

It was my akaunaarutiniapiga, great fortune, that these Inuit elders shared with me their perceptions, along with their words and expressions now seldom used and in some cases no longer understood. I learned that to be moved by the touch, the smell, and the sounds of the land was not unmanly. This sensual communion, this unganatuq, is a “deep and total attachment to the land” often expressed in spiritual terms. I am unable to forget how an old woman spoke quietly to me of nuna the land’s fearsome, deadly, and divine qualities with equal reverence.

From time to time, I wondered why the elders with whom I travelled gave so freely of their thoughts and assistance. They could see me capturing their words and putting them on paper, and with their permission, I made their words available for others to read. On rare occasions, I would be told not to disclose a certain event or fact for personal reasons. As time went on, I found that many elders in Cape Dorset actually looked forward to my visits, when I would record what was said over tea, bannock, and goodies. The range of names I was given reflects the different ways I was known to the Sikusiilaq elders: Apirsuqti, the inquisitive one; Angakuluk, the respected one; Inuksuksiuqti, the one who seeks out inuksuit; Innupak, Big Foot; Ittutiavak, a respected elder; and Uqausitsapuq, the word collector.

My Great Aunt Marie, centre, and our relatives in Bukovina, 1955.