Читать книгу An Intimate Wilderness - Norman Hallendy - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

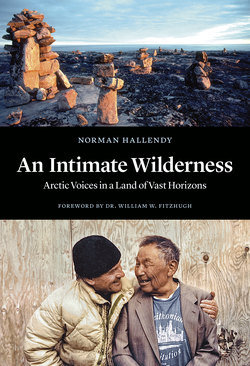

ОглавлениеSILENT MESSENGERS

There are places across the circumpolar world where the Inuit and their predecessors have left traces of their presence on the land reaching back thousands of years. The most enduring signatures of the Inuit are stone figures known as inuksuit — objects that act in the capacity of a human.

My interest in inuksuit began in 1958, on my first visit to Cape Dorset. Inuksuit could be seen in many places along the entire southwest Baffin coast. I photographed each inuksuk from at least three perspectives, wrote short notes about its location and orientation, and any other details that seemed relevant. During two summers travelling along the coast, I had produced more than 100 images and decided that it was time to seriously study these remarkable and puzzling figures. I wrote a polite letter of inquiry to most universities and other institutions in North America with an interest in Arctic studies. Of the five responses I received, four stated that they had no information on inuksuit in their holdings, and the fifth letter from a well-known Arctic archaeologist advised that the purposes attributed to “those cairns” were often exaggerated and serious study of them would be a waste of time. Instinct caused me to think otherwise.

At first, I attempted to classify inuksuit into obvious groups. I noted their morphology, size, the type of rock used, and a number of other physical traits associated with each inuksuk. What little written information I could find was included in my ever increasing pile of data and notes. That gave me a feeling of making headway, but the Inuktitut expression “he hides its meaning within words” gnawed away at me. I realized that by arranging and rearranging facts, I was merely conjuring an illusion of progress. In real terms, this seemingly logical approach had done little to increase my understanding of what had been revealed to me about inuksuit. Once again, I reviewed all the information I had collected: interviews, pages of field notes, and hundreds of photographs. No matter how I arranged and rearranged the data, insight was nowhere to be found.

Then one evening, while idly shuffling papers, I noticed that a single expression, utirnigiit, referring to traces of coming and going, appeared often in my notes. That word prompted me to examine my data in a new way. By grouping Inuktitut words and expressions related to utirnigiit, I created what I later learned to recognize as a semantic field. What emerged was a totally different way of perceiving the meaning of the things I struggled to understand.