Читать книгу An Intimate Wilderness - Norman Hallendy - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTOUGH GUYS AND GENTLE MEN

I first became conscious of manhood in 1948 at the Annual Prospectors’ Convention in Toronto. I was sixteen years old. As I remember it, the convention was a spirited gathering of men and women who worked in the mining industry in the North. The majority who attended the convention were, of course, prospectors. This was when they came together from all parts of the North to celebrate the coming field season, renew old friendships, scout the territory for new jobs, swap yarns, and enjoy a moment of nirvana before setting out on their lonely trails in search of El Dorado.

My parents came to Toronto in 1917 from Bukovina, a region in central Europe. At the time, kissing the holy icon on Sunday and being on the lookout for the evil eye on all other days was quite normal. I have hardly any recollection of my grandparents beyond the fact that they were quite superstitious. My father’s family were like serfs whose struggle to eke out a living left no time or reason to fashion a family tree. Like countless other immigrants, they came to the promised land not because they believed the streets were paved with gold but to escape the endless brutality that seemed to be their birthright.

Like most immigrant and first-generation kids, my friends and I formed tribes, developed secret signs, held clandestine meetings, and swore to uphold the honour of our group. None of us had any idea that our respective parents were plotting to have us committed to institutions where we would forsake our roots and undergo the process of learning. We would acquire the instruments of success; our success would be their success; and so our parents would acquire status for the first time in their lives. To our parents, the sound of the wind rustling through the beech trees in Bukovina was only a distant dream.

As a youth, I learned important life lessons by working odd jobs. Even at a tender age, I learned that diversity of experience was the pathway to success. At age fourteen, I landed a summer job at a doll factory as a gofer and floor sweeper before progressing to the production line, making Baby Wett’em dolls. I also worked in a graveyard raking leaves and filling in groundhog holes. The giant leap forward was becoming head boy in the fresh produce department of Canada’s largest grocery chain.

To my parents, these early jobs were all fine, but having sent me to private school, they were of the opinion that I would surely become a doctor, a lawyer, or, at worst, an engineer. They were utterly dismayed when I blithely announced that I had decided to study art. The decision seemed perfectly natural to me. I had always had a strong instinct for curiosity and a means of expressing it at a very early age. Art appealed to me because it had a magical quality that defied scientific explanation. But when my father, who clearly thought that studying art was a cop-out from the real world, asked me to explain this direction, I fumbled. He told me then that my future was in my own hands and I best put them to work as soon as possible.

To the family of Alexei, Sending you my photo for your children and mine to remember. Giving you many hugs and kisses forever.

Until we see each other again,

Frozina

2 November 1958

I quickly discovered that in order to earn enough money to pay for school, buy books and supplies, and have a little pocket change, I would need to work up north for the entire period I was not attending school. “Working up north” was a euphemism for having a job in either the mining or forestry industry. Natural resources companies offered the relatively well-paying seasonal jobs that appealed to students like me. I had no romantic notions about the North — I was going there out of necessity. Getting there would not be difficult. The real problem was convincing an employer to hire a sixteen year old kid with no experience in the field. I caught a break when I came across a notice in the Toronto Daily Star announcing that the Annual Prospector’s Convention would take place at the Royal York Hotel. Dressed as neatly as possible, with two dollars and a ten-cent streetcar fare in my pocket, I was off to the most important convention of my life.

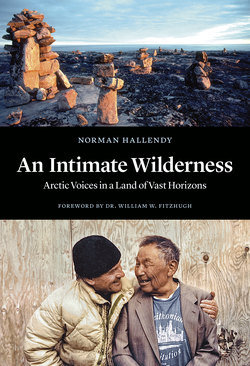

The Moldavian side of the family, 1954.

A sixteen year old packing a box of high explosives unaware it’s leaking nitro glycerine.

Amid the raucous gathering of those tough miners, I felt a sense of belonging. I knew I was in good company. I met Eddy the Swede, Johnny B., Louis Four Toes, and the unforgettable Big Biff Breakey, who once said to me gruffly, “I’m gonna hire you kid, but if you ever let me down, you’re out’n your arse.”

That spring, before I headed into the bush, my father gave me a .22 rifle and a piece of advice: “Never work,” he said, “for anyone stupider than yourself.” The next day, I boarded the train to Lake of the Woods on behalf of the Northern Canada Mining Company to locate and re-examine an abandoned gold mine. That evening, under the spell of the clickety clack of the coach’s wheels, I fell into a deep sleep. The next morning, I awoke to a sight that astonished me. Entering the boreal forest, I saw a sea of trees flashing by my window. I had seen forests and woodlands but never such a powerful living thing as this. The forest evoked in me a sense of wonder and imagination I had never known.

I would experience dwelling within this great living thing. Each night, the forest seemed to pulse with a mysterious presence. The sounds coming from deep within were those of owls, loons, foxes, wolves, and the clacking of hooves. Occasionally, my heart skipped a beat as a branch broke loudly and sharply somewhere in the darkness. Some nights in the boreal forest were filled with wonder, when the very air seemed to crackle beneath a blanket of stars showering the Earth with their brilliance. Under a rising full moon, I felt as if I were being drawn into an ancient spell.

One starry night while watching the silhouettes of geese flying south, I experienced the most beautiful event in these northern latitudes, the aurora borealis. It was unlike any display of the northern lights I had ever seen. At first, a faint wisp of light drifted between the stars, a hint of a heavenly event. Then this faint wisp appeared to grow in strength. It became ever brighter, gathering colours from some unseen source. Like some great luminous curtain, it began to unfold across the sky as if set in motion by a celestial wind, its hues changing each moment. The once darkened sky was transformed by this mysterious expanding radiance. Next, as mysteriously as the aurora had arrived in the night sky, she began to fade and the stars, once pale, now regained their original brightness. Having seen such beauty, having stood beneath a moon wrapped in a blanket of stars while listening to the haunting voices of wolves, I entered a wilderness of one, where each footstep led to some new thought.

My life in the forest was filled with many happy experiences. I worked with rough and tough son-of-a-gun men who were never unkind and who would look out for one another. They didn’t write poetry or read the writings of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. They worked hard and from time to time sought out their own private spaces. If some knew that I saw them enjoying a sunset or standing with outstretched arms in a howling wind, I am sure they would have growled in embarrassment and told me to bugger off. In a notebook that I kept under my bunk, filled with observations, expressions of feelings, and random thoughts, I wrote, “I feel a sense of belonging here, yet I don’t know why. I’m almost afraid I’ve been lured into some strange chimera.”

One evening, I began to write the words and expressions I was learning in Ojibwa from a Native elder who lived in a nearby camp. The elder came into our camp looking to buy tobacco, paper, and matches. He had taken a shine to me, as I was about the same age as his son. I had asked him if he would teach me a few words in Ojibwa. When I had repeated them to him, he was astonished that my accent sounded perfect. I put this down to the fact that my first language was a Slavic one (a Bukovinian dialect of Ukrainian), in which the phonetics were quite similar.

The elder’s camp was only a few kilometres from ours, and on each of his visits, I would ask to be taught a few words, which I would write out phonetically. I learned the names of familiar things — birds, animals, the method of making a fire. I learned evocative expressions such as “the sun which shines in darkness” (referring to the moon) or “the place of talking waters” (referring to a nearby set of rapids). The Ojibwa elder talked of once travelling in a great schkoodayodabah, meaning the great fire sleigh or railway train. He talked of forest spirits, leaving gifts to the land, and the importance of showing respect. The one thing he never told me was his name. He simply referred to himself as neweecheewahgun, meaning “a friend.”

Each year, I returned to the North, leaving behind the amenities of the city, the pleasures of school life and good friends, and began to discover an awareness of the eternal beauty of the wilderness. I would see some new place, gain valued experience, and think about things only they could evoke. Each year, I found myself moving ever northward. No longer doing the bull work of my earlier days, I was now a partner in a reconnaissance team. We moved quickly on foot across the landscape, mapping hundreds of square kilometres in a single season. That sense of self-reliance learned while working under the eye of experienced old-timers became more important than ever. Now I often travelled alone. With only a one-day supply of food, a knife, matches, map, compass, and notebook, I ventured out each morning, with the expectation of a safe return each evening to a little tent somewhere in a vast wilderness. Often at night before falling asleep, I would conjure a fond memory; in reliving it, I would soften the sharp edge of loneliness. I would fall into a deep sleep, often visited by dreams too ethereal to remember. Upon awakening to the smell of spruce needles and sunlight entering the tent, I found that the lure of distant hills replaced the sense of loneliness.

In Ungava now called Nunavik (Arctic Quebec) at the age of seventeen.

In the early summer of 1949, I was no longer in the forest. The only trees I encountered were no higher than the length of my hand. I was now in the Arctic, where the earth remained permanently frozen. I was surrounded by a vast horizon, a sight I could never have imagined. Until that day, the Arctic of my imagination had been only a barren and icebound landscape. It was the most forbidding place, shaped in the mind’s eye by heroic tales and films that dramatized the land and its people. Even the numerous and often startling photographs I had seen merely confirmed my impression of a frightfully beautiful, frozen corner of the planet. In the years to follow, the Arctic I would come to know extended far beyond the boundaries of my imagination.

The powerful landscape of the Pangnirtung Pass (Pangnirtuuq), Baffin Island.