Читать книгу An Intimate Wilderness - Norman Hallendy - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

When Martin Frobisher arrived in the Canadian Arctic in 1576, searching for the Northwest Passage in three small sailing vessels, the Inuit had lived here for only about 250 years and had already experienced major environmental and social change. They had replaced the previous Dorset inhabitants (known to Inuit as Tuniit), had met Norse and Elizabethan explorers, had acquired iron, and had seen their major subsistence resources — bowhead whales — disappear as the Little Ice Age closed down their summer waterways. This is not exactly the image of the “timeless” Arctic people that emerged from the late 18th and early 19th century ethnographies of Franz Boas and Birket-Smith, and Knud Rasmussen, a folklorist; and it pales before the realization that Inuit predecessors — the Dorsets and/or Tuniit — had been living here four thousand years. Yet, as Norman Hallendy demonstrates, during their relatively brief tenure the Inuit built a world that is richly preserved — not only in artifacts, campsites, and ethnographies — but in the little-investigated field of Inuit language and toponymy.

Norman Hallendy’s long-term relationship with the Cape Dorset region of southern Baffin Island brings us closer to understanding the world from an Inuit perspective than anyone since Rasmussen, whose work and publications from the Central Arctic in the 1920s first documented linguistic aspects of Inuit culture. Hallendy did not come to these lands as an anthropologist or explorer. This first generation Canadian immigrant with heritage from Bukovina in Eastern Europe wandered into the Canadian Arctic by chance as a mining prospector’s assistant; he became captivated by its people and geography, and for the next forty-five years returned again and again, mesmerized by the vastness of the land, his genial hosts, and the spell of the evocative Inuit language. During seasonal visits to Cape Dorset as a high-ranking Canadian Government housing official he began to explore the meaning of words, concepts, and place-names. Over time his social ties with the Dorset community, particularly elders whose early years had been spent living in camps throughout the year, grew into trustworthy bonds. Visiting homes, travelling far and wide to inspect old camps (nunalituqaq), historic and sacred sites (saqqijaaringialik), and places of power (itsialangavik), he has come closer to seeing through Inuit eyes and thinking in Inuit ways than any previous visitor to the Canadian North. Learning Inuktitut and working closely with translators and knowledgeable elders, he recorded nuanced words for places, states of mind, and relationships, and has made these words and their meanings available in an extensive linguistic database unique to Sikusiilaq (Foxe Peninsula). Hallendy’s work in Cape Dorset is likely to stimulate interest in preserving linguistic concepts among Inuit elsewhere.

Hallendy’s explorations have made him something of a modern ‘Rasmussen’ of the Canadian Arctic. Rasmussen was more interested in Inuit mythology, religion, and oral history, whereas Hallendy focuses more on lexical matters like names, meanings, and states of being. Like Rasmussen, he travelled and lived with Inuit, winter and summer, exploring the words Inuit use to describe weather events, ice conditions, or geographic and cultural features. Called by Inuit Apirsuqti “the inquisitive one,” Hallendy developed friendships that provided him with access to inner worlds that anthropologists since Rasmussen have ignored or taken for granted. No one before has explored the connections between Inuit conceptions of place, geography, and philosophy in such depth. It is indeed, for the Inuit and for Hallendy, an “intimate wilderness” created through the meaning of words that he reveals in a memoir written as an autobiographical tribute for the Inuit who opened their world to him.

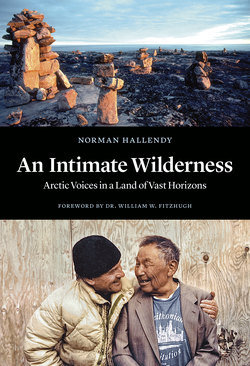

Hallendy is best known through his interviews and lectures and for his documentation of the Inuit stone structures known as inuksuit (“acting in the capacity of a human”), whose singular form is inuksuk. His beautiful photography and book, Inuksuit: Silent Messengers of the Arctic, illustrate these mysterious rock sculptures, revealing them not only as works of art but as structures with special meaning. Today their most iconic forms have become symbols of Inuit ethnicity and Canadian national identity. In Intimate Wilderness we meet more of these creations and learn their meanings and stories as told by Inuit elders.

Because of his previous book Inuksuit: Silent Messengers of the Arctic, the once-enigmatic inuksuit and their stone relatives are not as mysterious as they once were; they have Inuit names and meanings and tell stories that add to our knowledge of Inuit and Tuniit history.

Intimate Wilderness tells many stories in different ways. It is a memoir, a tribute, a linguistic ethnology, and a story of lives and history in a small part of the Canadian Arctic whose lexical world has never been studied in such depth before. For thousands of years Inuit Paleoeskimo ancestors created a world we know only through abandoned houses, stone tools, food remains, and tiny but beautiful carvings of people and animals.

By eliciting memories of them and their names from the few Inuit still directly familiar with the old Inuit way of life, Hallendy gives us a glimpse of a world that before, was closed to all but the Inuit themselves, a world that may even include some Tuniit history. While we will never fully understand the full significance of their ‘silent messengers,’ through the narratives and words the Cape Dorset people use to describe their landscape, Norman Hallendy has cracked the door and provided us a glimpse of this land of vast horizons.

William W. Fitzhugh,

Director, Arctic Studies Center,

Smithsonian Institution,

Washington DC.