Читать книгу An Intimate Wilderness - Norman Hallendy - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

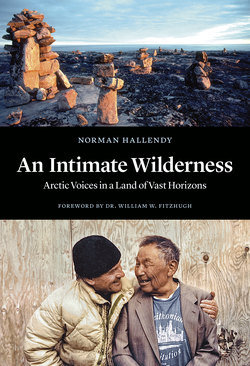

ОглавлениеFIRST IMPRESSIONS

For my generation, getting up to the Arctic was easy. Weather permitting, I could fly to the most remote regions in a day or two. Yet just a single generation before mine, those hearty souls who ventured north were resigned to the prospect that it might take them at least a year or longer, depending on the weather, to reach their destination. At that time, getting to the Arctic was by way of train to the end of the line, then a stomach- churning voyage on a small supply ship, often followed by walking and sledding enormous distances. There was no food supply from the outside world, no global positioning system, no sideband radio. The essentials were simple: Learn from the Inuit how to survive, make no mistakes, and regard hardship, no matter how severe, as a natural occurrence to overcome. Savour a sense of personal triumph, however small. In those early days, grants, steady wages, or sponsors were rarely available to those travelling to the Arctic. Many paid the costs of doing their fieldwork out of their own pocket.

I arrived in Cape Dorset — or Kinngait as it is also referred to — in 1958, when I was 26 years old. At the time, I was working with the Department of Northern Affairs as an industrial designer. The department did groundbreaking work, such as developing the Arctic char fishery, a lumber operation on the George River, and, most important, a network of Inuit cooperatives across the Arctic.

When I arrived, Cape Dorset was a pleasant community of about 700 people, many living in flimsy shelters known as “matchboxes.” The town faced the sea and was blessed with good hunting in the surrounding area. A few people were still living in permanent camps along the coast and came into Dorset to trade with the Hudson’s Bay Company. At the time, probably fewer than 100 qallunaat, white people, lived in the entire eastern Arctic (excluding military personnel). This number would swell each summer when a few dozen scientists arrived just in time to feed our little leituriaraluit, voracious mosquitoes.

In those days, many Inuit of southwest Baffin Island, historically known as Sikusiilaq, were still living on the land. Though they were equipped with rifles and an increasing number of articles obtained from the qallunaat, staying alive still meant securing enough food to keep from starving, fashioning one’s own clothing and shelter to keep from dying of exposure, and rearing children who were expected to be future providers. Such was the taimaigiakaman, “the great necessity.”

It was with these people of Cape Dorset that I would develop a lasting friendship. Many had recently started living in settlements. They left behind articles designed for living entirely off the land. They brought to Cape Dorset few material goods — perhaps a harpoon for seal hunting, a stone lamp handed down from mother to daughter, and other assorted articles of sentimental value. They also brought vivid memories of their traditional way of life and enduring perceptions of both the physical and metaphysical world that continued to exist just beyond the visible limits of their new settlement.

The familiar expression “going out on the land” meant leaving the often mundane life in the settlement. Going out on the land also meant journeys upon the sea or ice to locations dear to the heart: returning to the places of one’s childhood and family life, to favoured locations on the tundra where caribou grazed, or fishing spots where, during twilight hours, one could listen to the haunting cry of red-throated loons.

Upon my arrival in Dorset that first year, one of the people I met was Kananginak Pootoogook. The son of one of the most powerful camp bosses on Baffin Island, Kananginak represented the generation of Inuit who had been born on the land and lived long enough in traditional camps to learn many traditional skills. Kananginak and his contemporaries later moved into settlements with their elders and became the first generation of Inuit exposed to a qallunaat way of life.

Kananginak was a sturdy man as a result of years of hunting and tending his father’s traplines which extended for hundreds of kilometres throughout the Foxe Peninsula. Though he had come to live in Cape Dorset as a young man, Kananginak retained a strong attachment to the land. His remarkable drawings of wildlife, traditional camp scenes, and contemporary themes are well known to Inuit art curators and collectors in North America and Europe. One of Kananginak’s last drawings is a small map he did for me documenting his family’s immediate hunting area in Kangisurituq (Andrew Gordon Bay).

Though Kananginak and I had known each other since 1958, in the early years we never sat down for a good chat. We would often just trade good-natured insults, shake hands, and be on our way. Only in the later years of his life when we finally came together did he make known there were things he would like me to record. In these conversations, Kananginak spoke movingly about how he had perceived life when living on the land and how living in a settlement had affected him.

What I’m about to tell you is how I remember life as it was on the land when we lived at Ikirasaq. Our entire life was spent looking for food. Just think about that! Staying alive depended on knowing where to look and when to look at places where the animals would be. We were always on the move. We travelled by boat, sled, and most often we walked.

Entire families would take everything that was needed for the journey. We carried everything on our backs. Some of us were lucky enough to have a few dogs who would carry things on their backs as well. The man and the eldest son would carry the hunting equipment and the heaviest things. We would carry the tent, bird catcher, throwing stick, fish spear, antler knife, bow drill, a special rock to make fire, and bows and arrows. It was necessary to carry sinew, pieces of ivory and bone and other materials so you could repair things along the way.

It was important to make extra arrowheads before setting out. Especially beautiful and accurate arrowheads could be made only during one day in the year. They were made by using the last rib of an udjuk [square-flipper seal]. Of course, arrowheads were made at other times but lacked real importance. All kinds of other things were brought along, but the most important was the harpoon. You see, the harpoon has many functions. It is used for hunting seal, walrus, and whales. But even when travelling inland, it has many uses. It can be quickly converted to a spear by changing its tip. It can be used as an ice chisel, a snow probe, a rod to help someone in need, and other useful things, but most importantly, as a weapon to defend yourself.

The wife and daughter had much to carry on their backs. They carried pieces of scraped skins to repair clothing and caribou skins to lie upon. They brought needles, sinew, thimbles all placed inside a bag made from a loon skin. The woman carried a stone ulu [women’s knife] skin stretchers, one made from stone, another from the scapula of a seal, and a special one from the shin bone of a caribou. They carried the extra clothing, the qulliq or kudlik [soapstone lamp], a small bag of moss for the lamp wick, soapstone pot, and a skin bucket and dipper made from sealskin. She brought dried seal meat and blubber to burn in the lamp, as well as to eat along the way until the men got fresh food. Because the women must keep clean, they brought seagull skins to clean their hands and rabbit skins for when they had their period. Rabbit skins are also good for wiping the baby’s bum and the skins from the rabbit’s legs are carefully peeled off to be used as finger bandages. The woman brought a scraping board for cleaning skins, together with tent poles and a drying rack.

With all this, she would probably be carrying a baby in her amaut [parka hood]. She knew how to carefully remove the skin from small birds and turn the skins inside out. They become nice warm booties for babies. Women had to keep up with the men while carrying all these things. If a woman gave birth along the way, by late the same day she put the baby in her amaut, picked up her belongings, and continued on with the rest.

Our journey inland would begin in the season when the caribou have short hair [toward the end of August]. Different families lived in different places all the way from Nuvudjuak to Sugba. There were 14 main camps in our region and many seasonal camps all along the coast. The people in our region who lived the furthest away were from Nuvudjuak and Nurrata, and so their journeys were across land and began in the northwest. The families who lived below Tikiraaqjuk, the great finger, would meet at a few traditional gathering places at the Sugba. It was important to know the whereabouts of the katittarvit sinaani nunaqpagiarnialiqtunut [gathering places on the shore in preparation of going inland]. It was here where families gathered checked everything and discussed their plans before setting out for the great walk. It was a place and time of excitement. It was here that we left some things behind, carefully cached for our return just before the sea began to freeze in early November. We would pick up all our belongings put them on our backs and begin the great walk inland.

We all would start walking as soon as there was light and each day walk as far as we could. Some parents were careful to watch their small children during these long periods of walking because the young children could suffer a painful dislocation we call azalujuk, which is the same expression used when the runners of a sled start to splay outward. The men hunted along the way, thankful that fresh food was had to replace the dwindling supply of blubber and dried meat.

The older men would point out landmarks to their young sons. The boys were learning about the meaning of life... survival. They would memorize the shapes of distant hills. They were taught how to observe all the things around them. The angaituq [the specialist] was our teacher.

In those days our people had very strong ways to describe things, especially the landscape. The expression tauuunguatitsiniq means creating a picture of a thing in another person’s mind. Our maps were in our mind. We knew the places where one had to be very cautious. We had pictures in our head where animals would likely be at certain times of the year. We knew the favoured locations of caribou and where they would cross rivers. We knew where we could cross rivers in search of them. And when the crossings were too deep, we would take a caribou skin, shape it into a bag, stuff it with dry moss, and paddle safely to the other side. One of our most important maps we had in our mind was a map of all the shallows, the ikaniigiik. Without it, travelling over long distances would be very difficult.

We gathered together before starting out, as I explained, and often would start out going inland as a group. Later we would separate into small family groups, each going to its preferred locations along a familiar route. By the time we reached the places where the caribou were plentiful, their coats were in the very best condition. Understand that though seals were our main food supply, caribou were vital for our survival in winter. From their back came the sinew to sew their skins needed to make the winter clothing that kept us from freezing to death. The meat and the marrow from their bones nourished us. We used portions of their antlers to make tools. We dressed in their skins. We slept on their soft skins in a warm tent made of their skins. It was as if for part of a year we lived inside a fat, warm caribou.

Sometimes we would agree to meet again at certain places along the way but, most certainly, we would agree to meet as a group at the end of our journey inland north of Natsilik [Nettilling Lake]. It would take at least a month to reach it. By then our journey was only half-completed. We began our return home at the time when days and nights were of equal length [late September]. If a certain family did not show up within a few days of our agreed departure time it was no big worry; they may have had some reason to stay awhile or take a different route for part of the way. The time we began to show some concern is when we got back to our main camp and there was still no sign of them. Some people would decide to winter over at Natsilik, especially if there was a lot of food around.

By the time the caribou had mated, the sea ice was becoming thick enough to travel upon [mid-November]. If one was fortunate to have a good dog team, we would make the journey all over again to Natsilik, but this time it was easier, for we travelled by sled. Because the conditions of snow and ice could change from day to day, one had to know how to get to a desired place by many different routes We not only hunted we also trapped white foxes. Now it was important to know which lakes and rivers had treacherous places where the ice was always thin even during the coldest time of the year. It may surprise you, but we sometimes met Igloolikmiut [people who had travelled all the way from Igloolik] at Natsilik. We would hunt and trap during the winter and once more return to our camps at Sikusiilaq about the time when the ringed seals were born [late March].

When you were young it was important to be on the land with an angusuitug, a good hunter, a very competent person. Your mother and father gave you life but it was from an angusuitug that you learned how to stay alive.

Pingwartuk who gave me the secret of staying alive.