Читать книгу An Intimate Wilderness - Norman Hallendy - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNUNANNGUAQ, “AN IMITATION OF THE EARTH”

Travels with Inuit companions inland, on the open sea, or on the ice without a map or compass never ceased to amaze me. This was especially true when we kept moving while enveloped in dense fog at sea or wrapped in a blizzard.

“Maps” were registered in memory as a series of images illustrating features, places, and related objects located in a temporal and spiritual landscape. Each one of these entities had names. I was able to document 230 different geographical terms in Sikusiilaq alone, ranging from the simple nuna, the land, to laumajurniavissagalaaluit, areas that can support life, to najuratsaungittuq, places forbidden to ordinary human beings, places where evil things were practiced. Inuktitut terms for hills, rivers, lakes, eskers, and mountains were familiar to people living in widely separated regions. I found that topographical names collected in Arviat are almost identical to those throughout the Foxe Peninsula.

The names of places and objects, however, often reflected how they appeared to the eye and thus how they were imagined. The images they evoked were multi-dimensional, recognizing that their appearance varied depending on the relative position of the traveller, season, or position of the sun. Because the Arctic landscape changed about every hundred days, these cognitive maps were dynamic, reflecting the prevailing conditions of the seasons, weather, and tides.

Nurrata, on the east coast of the Foxe Peninsula, is an example of an ephemeral landscape whose character is reflected in the name of an ancient site. The name Nurrata implies, “where the land and the sea appear as one in winter.” Nurrata lies in the region of Qaumarvik, which is the region beyond Tikiraaqjuk, the “Great Finger,” or the peninsula pointing to Southampton Island. Thus one could construct a vivid mental image as follows: beyond the place of the great finger where the land is in brightness lies the place where there is no boundary between land and sea in winter.

Some places had more than one name. They would have a common name known to most in the region and an arcane name not disclosed to outsiders. An example of such a place is Igaqjuaq near Cape Dorset, southwest Baffin Island. Igaqjuaq is described as “the overturned kettle” because of its appearance, but its name implies a great fireplace, suggesting a place of feasting. Its archaic name is Qujaligiaqtubic, according to the elders in Dorset, a name so old that its exact meaning is no longer known. An elder interpreted Qujaligiaqtubic as, “the place from which one returns to Earth refreshed”. Qujaligiaqtubic was where the people of Sikusiilaq had gathered once each year for generations to celebrate the ancient fertility ritual of siiliitut.

There were places, essentially retreats, known only to women, who referred to them as arnainnarnut qaujimajaujuq. Men could merely speculate about what occurred there and ascribed little importance to such places except to acknowledge that they existed.

If you examine a contemporary map of the Foxe Peninsula and superimpose the traditional travel routes of the Sikusiilarmiut, it is difficult to comprehend how entire families travelling on foot, laden with children and gear and confronted by countless bogs, rivers, and lakes, could find their way there and back on their annual journey of well over nine hundred kilometres. During these journeys, the most important consideration was where one could safely cross rivers; the complex geography was one of shallows that could vary in depth depending on the prevailing conditions. The vital element that the families added to the visible landscape is where they could find food along the way. It was essential to know the locations for intercepting caribou, finding geese, and, if need be, catching fish. There were no paper maps, no way-finding tools, only memory providing a sense of direction. Occasionally they would encounter an inuksuk known as a nalunaikkutaq, literally “a deconfuser,” placed in a strategic location during some forgotten time to help the traveller.

These mental maps could be translated to sand, snow, or even paper if need be. There are several accounts of Arctic whalers and explorers who engaged Inuit as pilots and map makers. One such account can be found in Robert Huish’s book on the travels of Captain Beechey along the coast of the Bering Strait in 1826.

On the first visit to this party, they (the Eskimos) constructed a chart of the coast upon the sand, of which, however, Captain Beechey at first took very little notice. They, however, renewed their labour and performed their work upon the sandy beach in a very ingenious and intelligible manner. The coast line was first marked out with a stick, and the distances regulated by the day’s journey. The hills and the ranges of mountains were next shown by elevations of sand or stone, and the islands represented by heaps of pebbles, their proportions being duly attended to. As the work proceeded, some of the bystanders occasionally suggested alterations, and Captain Beechey removed one of the Diomede Islands, which was misplaced. This at first was objected to by the hydrographer, but one of the party recollecting that the islands were seen in one from Cape Prince of Wales, confirmed its new position and made the mistake quite evident to the others, who were much surprised that Captain Beechey should have any knowledge on the subject. When the mountains and islands were erected, the villages and fishing stations were marked by a number of sticks placed upright, in imitation of those, which are put up on the coast, wherever these people fix their abode. In time, a complete hydrographical plan was drawn from Point Darby to Cape Krusenstern.

That remarkable map depicted the entire coastline of the Seward Peninsula of Alaska, approximately 1,000 kilometres in length.

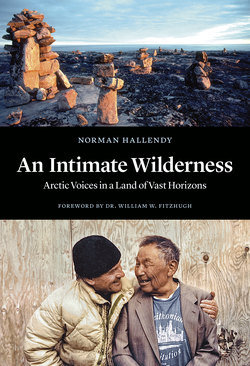

In my collection of over 100 maps there are three kept among my treasured objects. They are nunannguait, imitations of the earth, drawn by Kananginak Pootoogook, Simeonie Quppapik and Ruth Qaulluaryak.

Kananginak Pootoogook’s Nunannguaq

Shortly before Kananginak died in November 2010, we spent a quiet afternoon reminiscing about the old days. I had been to Ikirisaq, the famous and now abandoned Pootoogook camp on the east side of Kangisurituq (Andrew Gordon Bay). I expressed the regret that we had never travelled to all the favoured locations around Ikirisaq together. In my heart I knew we would never make that journey because Kananginak had only a short time to live. On the last day we would see each other alive, he handed me a a small sheet of paper, it was his nunannguaq (above) depicting all the favoured locations around Ikirisaq that we had hoped someday to visit together. Perhaps we will.

Simeonie Quppapik’s Nunannguaq

Simeonie drew two maps for me. The first shown here (opposite) drawn in 1990 depicts the coast of southwest Baffin Island, from Cape Dorset (far left) to Simeonie’s birthplace near Qarmaarjuak (Amadjuak), some 300 kilometers distant. He identifies the location of whales, square-flipper seals, walrus, small seals, fish, birds, etc. He shows the migration path of geese and the reindeer herd once tended by the Sami Laplanders, (see the chapter on The People With the Pointed Shoes) at Qarmaarjuak (HBC Amadjuak Trading Post).

The inuksuit he illustrates across the top of the drawing are those he describes as the “important ones” that relate to major sites of ancient ceremonial centres, fish weirs, where Tuniit once lived as well as other significant places. He is careful not to relate an inuksuk to a specific place thus revealing the location of what we would interpret as a “sacred site.”

Interestingly, he hints of such a place by including a figure which is not an inuksuk. The sixth figure from the left is in fact a tupqujak, a shaman’s doorway located at Kangia (Kungia). This wonderful map has been exhibited in numerous exhibitions and publications in Canada and abroad.

Ruth Qaulluaryak’s Nunannguaq

Many years ago a delightful young lady gave me a little tapestry (see page 80) which has hung in my bedroom all these years. I was told that Ruth Qaulluaryak who lived in Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake) in Nunavut, made the tapestry. Though I had been in Baker Lake for short visits on three occasions, I had never met Ruth. I learned a little bit about her early life through a friend who lived in Baker Lake. Ruth was born and grew up in Haningayok the back river area of Kivalliq, the Keewatin region in Nunavut. She was born the same year (1932) as I though our childhood experience could not be further apart.

Tapistry, 17 ”x21”, by Ruth Qaulluaryak,

Baker Lake (Qamanittuaq), 1969.

A depiction of her universe.

Her family and her people lived a life governed by the movement of caribou. Periods of starvation were not uncommon in the region. I was informed by elders in Arviat that they knew of families starving to death in the interior as late as 1958. It was only in 1970’s that the Qaulluaryak family reluctantly left the land they knew, and moved to Baker Lake.

The landscape familiar to Ruth was a somber one unlike the often spectacular vistas found in the eastern Arctic. It is a landscape which is relatively flat, covered by snow for much of the year only to emerge for a very short time draped in somber shades of grey and brown. For a few weeks there is a patchwork of various shades of green with pockets of Arctic wild flowers whose beauty lasts for a number of days rather than weeks.

It should come as no surprise that a child growing up in a land that often provided such hardship would behold it, as a painful memory of a forsaken place. With this brief narrative as our backdrop, let’s look at Ruth’s tapestry. At first we see a small polar bear amongst a field of various coloured flowers. Her tapestry appears to be a charming little decorative wall hanging. However, look more closely.

The landscape, the sea and the sky are defined by a myriad of flowers. They vary in shape and colour denoting those that live on the land or grow by the seashore including the plants that live in the sea. The only two figures not defined by flowers are the polar bear that moves about the land and in the sea and the thin yellow ocher line that defines the sea from the land. Just above the polar bear’s head, we see a white patch of early spring snow on the ground. Some “flowers” appear monochromatic suggesting shrubs, lichens and grasses while others are brightly coloured illustrating the great variety of flowering plants that carpet the tundra each brief summer. If you look at the top left side of the tapestry, you notice flowers placed on a midnight blue background. The background represents the night sky and the flowers represent the stars. Notice the flower in the top left corner of the sky. It is larger than all others. It represents Nikkisuitok, the pole star we call Polaris. Ruth’s nunannguaq of the earth, sea and sky is portrayed by flowers symbolizing a great living thing, of beauty and renewal.

Satellite image of the entire Foxe Peninsula (Seekuseelak or Sikusiiliq).

Ivory and bone carving of a whale hunt, artist unknown.