Читать книгу Skylarks and Rebels - Rita Laima - Страница 10

Hello! Sveiki! (Latvian) Labas! (Lithuanian) Tere! (Estonian)

ОглавлениеI am very proud of the fact that I know part of my lineage, and that I can trace my roots back in time to places on the map of Latvia: Vidriži, Aloja, Birži, Augstkalne... There are some places in the United States that bear names of Latvian origin, like Livonia (Michigan), Riga (New York), and Riga Lane (on Long Island). We Latvians get a big kick out of this. I am proud of my two flags: our Latvian red-white-red flag and the Star-Spangled Banner of the United States of America. Latvian Jewish artist Roman Lapp’s hand from his exquisite series of drawings, “Hands for Friends,” is a perfect illustration of what I am. These colors symbolize my belonging to two very different cultures, which have made me the person that I am. One flag represents an obscure region of the Old World; the other symbolizes the New World and the United States and its break from the colonial fold. The United States of America remains the world’s brightest beacon of freedom and democracy: it has granted asylum to persecuted people from around the world. Among those were the Baltic refugees after World War II who could not return to their homelands on account of the Soviet occupation. My dual identity has undoubtedly enriched me.

I love the American motto “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” from the United States’ Declaration of Independence. These words are loaded with meaning and connotations, especially when I think about the other half of my identity—the Latvian side. Latvia’s quest for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness lasted a very short time, commencing in 1918 and coming to a violent end in 1940 with the Soviet invasion. While others rejoiced, World War II did not end happily for the Baltic States: for nearly 50 years these nations would be brutally oppressed by the Soviet communists. My grandparents barely escaped the “Russian bear.” So many Latvian lives were lost in the 20th century, that it is a wonder that our nation survived into the 21st century.

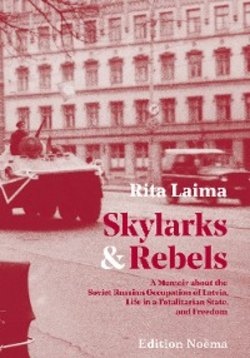

I spent 17 years in Latvia—from late 1982 until March 1999. Part of that time was under the Soviet Russian occupation (until 1991). My charmed youth in the United States propelled me to the USSR in a strange state of euphoria and fear. I think that basic American freedoms, the American way of life, and my exposure to a lot of culture from an early age—art, music, literature, theater, and cinema—went a long way in keeping me “charged” in the depressing Soviet era, when life was lived as if in an aquarium. American popular culture and humor also strengthened me for what I was to endure in communist Latvia. “Hogan’s Heroes” with Colonel Wilhelm Klink and Sergeant Hans Schultz had made us Latvian Americans laugh (although the Nazi occupation in Latvia had been exceedingly brutal and deadly). Totalitarianism would reveal itself to me in all its dark and dreary colors.

The words of many American and British rock songs would serve as a kind of buffer between my open and inquisitive mind and the oppressiveness of Soviet reality in the 1980s. “Where are you goin’ to, / What are you gonna do? / Do you think it will be easy? / Do you think it will be pleasin’? / (…) / It’s my freedom, / Don’t worry about me, babe…” (Steve Miller, “Living in the USA”) Unlike my compatriots in occupied Latvia, as an American citizen I had the freedom to travel, and I never took this freedom for granted. As soon as I was old enough, I wanted to get out of the house and see new places. First on the list was Latvia, which our family and Latvian American society had been talking about for years. Fantastically, my experience there would correspond with history in the making: “The present now / Will later be past / The order is rapidly fading…” (Bob Dylan, “The Times They Are A-Changin’”) You’re young only once. Pumped up by the energy of the music I listened to and bored out of my mind by American suburban life, I felt I was ready for anything. Even adventures in a place that US President Ronald Reagan would deem “the Evil Empire.”

Because so little was known about the Baltic countries during the years of the Soviet occupation, we were used to hearing many strange questions in the United States. For instance, my friend Gerry at Parsons School of Design wanted to know if people in Latvia wore clogs. “Is Russian Latvia’s official language?” “Are you Latvians Russian?” This obsession with Russia grated on my nerves. Luckily, the Baltic States have clearly emerged from Russia’s shadow, with many of my fellow Americans now recognizing the names of our countries. After independence in 1991, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian athletes have been winning medals at the Olympic Games to the cheers of Balts all over the world. (For example: Latvians Martins Dukurs [SILVER, skeleton, 2010 Vancouver] and Māris Štrombergs—aka “The Machine” [GOLD, BMX, 2008 Beijing; GOLD, BMX, 2012 London]; Lithuanians Rūta Meilutytė [GOLD, breaststroke 100 m, 2012 London] and Laura Asadauskaitė [GOLD, Modern Pentathlon, 2012 London]; Estonians Erki Nool [GOLD, decathlon, 2000 Sydney] and Heiki Nabi [SILVER, Greco-Roman wrestling 120 kg, 2012 London], etc.) After years of being forced to compete under the despised Soviet flag, Baltic athletes could finally compete under their national colors and hear their anthems fill stadiums around the world.

As an American in Soviet Latvia in the 1980s, I was a curiosity and a mystery. My Latvian heritage did not seem that important to anyone; it was the fact that I was American that was initially so intriguing to the people I encountered. Yet most of them were too scared to ask questions. Most Latvians could not understand what I was doing in Latvia in the first place, and this nurtured wild rumors. CIA, KGB… “Why on earth was I lingering on a sinking ship?” was the question I heard from time to time in the early eighties. (If the ship was sinking, that was a good reason to hang around, I thought.) As time passed, the curiosity dissipated; people lost interest when they grew used to my presence. (Rīga is not that big.) My strange haircut—an extreme mullet of sorts—grew out, and I blended in. Soviet leaders came and went, the tide of history changed, and the great “upheaval” began. A trickle at first but then building into a torrent of emotion and daring protest … The late 1980s were an unforgettable historical period of “national awakening” in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, prompted by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika and glasnost after decades of repression, the numbing beat of Soviet communist ideology, and economic stagnation under the Politburo’s heavy, all-controlling paw.

In my book I often refer to Latvia as the “fatherland,” because Latvians traditionally refer to their native country this way. “I placed my head on the boundary / To defend my fatherland; / Better that they took my head / Than my fatherland” are the words of an old Latvian daina or folk poem/song. You won’t find the word “motherland” in Latvian dainas and literature, but in artistic and especially sculptural representation Latvia is depicted as a woman. Latvia’s Freedom Monument in Rīga is the figure of a woman—the mother who gave us life and defends her children, as we should defend her. The word tēvzeme evokes feelings of patriotism and protectiveness. Our history has been marked by so many tragedies, that we all feel protective of our beautiful country.

As the mother of three sons, I have thought a lot about all the Latvian boys and men who gave their lives for the idea and reality of a free and independent Latvia (in the Latvian War of Independence [1918–1920] and during WWII), and about those who were forcibly conscripted into foreign armies (Nazi Germany’s and the Soviet Union’s Red Army, for example) and died in wars they should never have been a part of. Their countless names are impossible to list. Their bones are scattered across Latvia, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany, and elsewhere. Some of Latvia’s veterans from World War II still survive, cheered and cursed, their role in the last war misunderstood. The remnants of the Latvian Legion fought in the “Kurzeme Fortress” (also known as the “Kurzeme Cauldron”) against the advancing Red Army in World War II, helping thousands of Latvian refugees, including my grandparents and parents, to escape across the Baltic Sea to freedom. We Latvians have a duty to explain our complicated history, in which allegiances were forced upon us at gunpoint.

I also reflected on the women of Latvia—mothers, sisters, daughters, sweethearts, and wives who had to hold Latvia together with their bare hands and survival instinct. In the early 1920s National Geographic reporter Maynard Owen Williams visited war-torn Latvia and wrote: “[… This country] owes a heavy debt to its women, who drive the wagons, harvest the flax, pile up the grain, tend the cattle, sweep the streets, pull the carts, run the hotels, tend the street markets, keep the stores, shovel the sawdust, and juggle the lumber.” (Williams, Maynard Owen. “Latvia, Home of the Letts.” National Geographic Magazine October 1924) My grandmothers were typical Latvian women: stoic and ingenious, patient and persevering. One led her children out of harm’s way on a perilous flight across Europe from Stalin’s “Red Terror.” The other remained behind, cut off from escape by circumstance and responsibility: she and her young sons (my uncles) were among the millions of captives caught behind the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain.

The Baltic States’ geography has not been kind to its human populations. Numerous waves of war leveled much of what human hands built in the Baltic lands. Those busy hands went back to work time and time again. Despite these cycles of destruction, my people survived, and they are a fascinating bunch. Latvia, shaped like a peasant’s clog, is a repository of stories of tragedy and remarkable resilience: one only has to start digging, reading…

Ultimately, it is many people who made this book possible. My parents Baiba and Ilmārs Rumpēters and my grandparents, Līvija and Jānis Bičolis, and Augusts Rumpēters, instilled in me a deep love for the Latvian language and our cultural legacy. In my youth I basked in the light of my parents’ friends, writers, poets, painters, and musicians, most of whom have passed away by now. I mourn their absence. My children, Krišjānis and Jurģis (born in Latvia), and Tālivaldis and Marija (born in the United States), made me realize how important it was to tell my story and to document a decade of Latvia’s history under totalitarian oppression. My friends, especially in Latvia, helped me with my story by remembering certain details. The terrible suffering of the populations of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia in the last century was also a reason for working on my memoir. For too long the Baltic peoples had suffered without a voice.

A bit about my work on this book: I did much of my research online; I have strived for accuracy but am not a historian; and this is a memoir. I wanted to give my people a voice. I had to translate just about every source from Latvian myself (marked as Tr. RL). It is an endeavor of creative non-fiction. Many of the subjects that I mention can and should be pursued separately. The Nazi German and Soviet Russian occupations of the Baltic States deserve continued serious study. My book is laid out in such a way as to introduce the reader to my youth, which paved the way for adventures in my “fatherland.” I felt it was important to provide historical background information about Latvia in the 20th century; after all, events there explain why I was born in the United States.

So welcome to Latvia, a place I spend a lot of time thinking about, mainly because family and friends live there, and I think I would like to go back. My story is about being bicultural and exploring my family’s European roots. It is also a memoir about Latvia in its last decade as a satellite republic of the militarily mighty and fearsome totalitarian state, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In that unhappy union Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, independent and thriving countries before World War II, were reduced to the status of occupied provinces and nearly erased from world memory. I had the privilege of being in Latvia to witness firsthand the last decade of their oppression come to a much awaited end, as the “the Evil (Soviet) Empire” collapsed, and freedom was restored. Today that freedom is under threat again both from the outside and from within, and lessons learned in Latvia have provided a perspective on troubling times in Europe and, much to my surprise and dismay, in the United States.

Rita Laima