Читать книгу Skylarks and Rebels - Rita Laima - Страница 9

Introduction

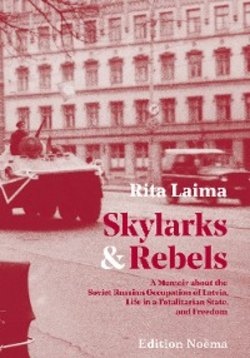

Оглавление“I want to live in a free Latvia!” A photograph from 1991 and the “Barricades” time. (Unknown photographer)

These are the memories that I carried around inside of me for years after I left Latvia in 1999. For a while I simply could not find the time to sit down and write; I bore two more children into the world, and their needs consumed me. When my daughter was born in 2005, I realized it was “soon or never.” Numerous unsuccessful job searches seemed to signal the urgency to turn to writing and try to capture the end of a dark era in Eastern Europe that many of my American compatriots knew little about. I had been there and lived through my “fatherland” Latvia’s last decade under the brutal Soviet Russian occupation, but not that many people knew where Latvia was or what life in the Soviet Union had been like. And in spite of independence, the future of Latvia, Latvians, and our beloved language, the key to our identity, remained clouded by uncertainty and tough economic times. This situation added to my sense of urgency. Nor was I getting younger. Each year seemed to dissolve into the last, compressing my sense of time.

While I dug into my memory, Latvians continued to emigrate from their native land in droves. Each year, as I became one year older, Latvia’s population diminished, with more people dying off than being born. There were many reasons for this, including the distant events of World War II and the Soviet occupation, which had a long-lasting, detrimental impact on the Baltic States. As I wrote, people of great significance to Latvia passed away, leaving a void. For a small nation each individual carries great weight. The oldest members of the former Latvian exile community (that is, my parents’ generation, which experienced the war) are dying off these days. Latvia’s demographic situation has become precarious. My story is about identity, language, patriotism, love, loss, and an archetypal landscape; it’s also about being young, idealistic, and fearless. I was full of curiosity, longing, and love when I traveled to the “fatherland” (tēvzeme in Latvian), the land of my ancestors, the country my grandparents were forced to leave due to terrible events beyond their control. My story will resonate with the descendants of Balts and East Europeans whose countries ended up behind the Soviet Iron Curtain after the war, whose families became refugees, and who sought to preserve their ethnic identity while becoming part of America. This is why I feel a deep kinship with my fellow Balts and with Poles, Ukrainians, Czechs, Hungarians, Jews, etc. Some of us still wonder where home is.

In this book I have retained diacritical marks to pay tribute to my mother tongue. Latvian, a very old Indo-European language, is the most basic and most important component of my identity. The United States of America is a country of immigrants, and Americans have come to accept all sorts of foreign names as part of their heritage. For this I love America.

As a first-generation American I am well integrated but not assimilated. I have no shame in speaking to my children in Latvian with Americans within earshot (I hope my fellow citizens do not consider me rude for doing so). I discovered that my fellow hockey, soccer, and school parents are a tolerant bunch. My Latvian language is a gift passed down through scores of generations, and I have no intention of breaking “the chain” of continuity. Our open American society makes me feel accepted. Our children’s American public schools display Latvian flags alongside other flags representing the countries of their students’ origins. What a great way to nurture American patriotism through the acceptance of its nation’s amazing diversity!

My son in his American team’s hockey uniform. (Family photo)

I enjoy reading the names on the jerseys of the hockey players we watch on the ice: it is also in those names that the diversity of America the Beautiful is revealed. Chinese, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Latvian, Polish, Russian, Swedish—names from all over the world—reflect the American nation’s history and essence. Life in Latvia in turn exposed me to its multi-cultural history. I became acquainted with Russia’s rich cultural and dramatic historical legacy and influence, even though in the Soviet era its positive effects on Latvian history were, mildly put, exaggerated and far-fetched. I was able to see a bit of Estonia and Lithuania while living in Latvia and realized again just how strategically important the relationship between the Baltic States is. In the 1990s I was able to easily travel to other countries in Europe. Stockholm, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Salzburg, Helsinki, Vienna, Venice… So many beautiful, wonderful, and different destinations could be reached from Latvia within a couple of hours of air travel. Living in Europe was exhilarating, and it made me realize that I was an amalgam of European and American influences.

Although I am Latvian, this book is also dedicated to Latvia’s Baltic neighbors, Lithuania and Estonia. The Latvian and Lithuanian (Baltic) languages are closely related. Old Prussian, now extinct, was once part of this language group. Estonian, the language of our hardy neighbor to the north, is a Finno-Ugric language and not at all like Latvian or Lithuanian. The Baltics are a distinct region of northeastern Europe with unique histories, cultures, and landscapes. My parents always spoke of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia as if they were members of a close family that had suffered the same fate in the 20th century.