Читать книгу Skylarks and Rebels - Rita Laima - Страница 21

Programmed for Latvia

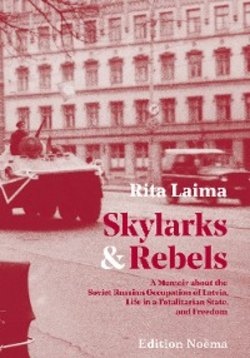

ОглавлениеA caricature of a pupil attending Latvian school by Latvian actor Reinis Birzgalis (1907–1990) from his book Letiņš trimdā (“Latvian in Exile”). (New York: Grāmatu Draugs, 1977.) Illustration courtesy of Rasma Vītola.

Our parents spoke only Latvian to us at home, laying it down as the law. “Runājiet latviski!” (“Speak Latvian!”) “Šajā mājā runā tikai latviski!” (“In this house we speak only Latvian!”) For years this mantra was repeated, while our ears were glued to the radio spewing American and British pop tunes and our eyes to the television set, which was brainwashing us with commercials about squeezable toilet paper, a man named Mr. Clean, and “Snap, Crackle, and Pop” cereal. We were enrolled in a Latvian School in Newark, which held classes on Saturdays. From an early age our weekends appeared ruined; these were innumerable days of boredom and suffering, which managed to set us apart from our American peers early on, creating a sometimes uncomfortable schism in our youthful identities.

My brothers and I each reacted to this cultural indoctrination differently. Unknowingly, I absorbed it deeply, and it has manifested itself in my priorities and choices, including moving to Latvia. At one time my older brother rebelled: he was turned off by Latvian society’s self-absorption and cliquishness. He succeeded in reconnecting with his Latvian side at the Latvian “2x2” camps and traveled to the International Latvian Youth Congress in Floreffe, Belgium in 1975. Much later in life he visited Latvia, where he felt like a reborn Latvian, blown away by the amount of history around him. My younger brother’s best friends were all Latvian, and he remained strongly connected to Latvian American society through his positive experience at Latvian summer high school in Pennsylvania, his marriage to a Latvian American, and his children’s school and camp. He embraced the life that the United States offered him. We were exposed to Latvian identity in the same way, yet we each chose a different route in life.

My parents and the vanguard of Latvian American society expected us to shoulder our legacy and carry it forward into the future, when the sun would rise over Latvia once more, figuratively speaking. They firmly believed this would happen, even as the decades of Soviet occupation wore on. Unfortunately, many of my peers of Latvian descent vanished into the American melting pot.

Our Latvian primary school, which moved from Newark to East Orange, provided a remarkably solid base for awareness of Latvia’s history and culture. While American kids threw baseballs and Frisbees and rode their bikes, we were glued to the hard wooden seats of our classroom’s chairs, where we practiced declensions and vocabulary, listened to lectures about Latvian history, wrote domraksti (essays) and endless diktāti (dictations), and took lots of tests. Latvian school improved my handwriting.

For someone like me, afraid of math and numbers, the memorization of important dates was torture. We were required to know the names of famous figures in Latvian history and when they lived, like Georgius Mancelius (1593–1654), Christoph Fürecker (1615–1685), Johann Ernst Glück (1652–1705), “Blind” Indriķis (1783–1828), Juris Neikens (1826–1868), Atis Kronvalds (1837–1875), Krišjānis Barons (1835–1923), etc. All of this, as well as poems and fiction and the rules of Latvian grammar, was stuffed into our pliable minds. Growing up Latvian was a lot of work and took up time that could otherwise have been devoted to leisure and fun activities.

Our Latvian history lessons ended abruptly with the year 1945. We were left with the impression that in 1945 Latvia was wiped off the map. All those cities, towns, ports, rivers, lakes, bogs, people, and bacon exports that we had to memorize seemed to vanish into nothingness. (Latvia’s lucrative bacon exports really did vanish under the communists.) We were left with many questions. As I grew older, I found out about family members living in Latvia. My Omamma was still there, receiving parcels of leopard and tiger skin pattern fabrics from Opaps to help her get by. Perhaps this abrupt end to Latvian history was unintentional, or there wasn’t enough time, or there simply wasn’t enough information to tell us what life in Soviet-occupied Latvia was like. In fact, we knew very little about the “forgotten” or “hidden” war—“the war after the war”—in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. This was the war of the “forest brothers”—our national partisans who valiantly resisted the Soviets by hiding in Latvia’s deep forests. Outnumbered, they would eventually be defeated, flushed out, and shot or deported. Another wave of deportations in 1949 would send tens of thousands of Latvians to Siberia. Decades of arrests and imprisonment in our part of the world continued after World War II. This part of Latvian history remained veiled to us for many years because of Soviet repression, secrecy, censorship, and hindered contacts.

Our school’s icy atmosphere and emphasis on memorization instilled us with fear and anxiety. Yet I still recall some stanzas from 40 years ago, such as Edvarts Virza’s (1883–1940) poem “Karogs” (“The Flag”)… “Pūšat taures, skanat, zvani, saule plašu gaismu lej! / Karogs sarkanbaltisarkans vējos atraisījies skrej. / Skrej pa laukiem, skrej pa klajiem, sauc arvienu dzirdamāk, / Lai no mājām, lai no namiem, lai no kapiem ārā nāk.” (“Blow the trumpets, sound the bells, the sun is spreading light around! / A red-white-red flag races unfurled in the winds. / ‘Cross fields and meadows it races, summoning ever louder / For all to emerge from houses, buildings, graves.”) Virza’s patriotic poetry was banned for the most part of the Soviet era. (Tr. RL)

Our Latvian school repertoire included dark, depressing songs about oppression, such as “Ej, saulīte, drīz pie Dieva” (“Hurry, Sun, to God”) about a black snake grinding flour on a stone. The song was about slavery under our former masters, the Baltic Germans: “A black snake ground flour / On a rock in the middle of the sea / To be eaten by those masters / Who made us work at night.” We also sang songs about abused orphans and war.

Many of the girls stayed after school to practice rhythmic gymnastics under our principal’s scrutiny, stretching and bopping around with hula hoops and plastic balls. Luckily, my parents didn’t sign me up. I was always very happy to scramble into the car and go home as soon as we were dismissed. One Saturday in my last year in school, as our principal was describing some dreary part of Latvian World War II history to us, I saw tears well up in her eyes. She struggled for composure. It was that fleeting moment, the crack in her steely armor, that made me realize she was human, that she had suffered, and that she had painful memories. That flash of emotion changed my perception of my teachers; I forgave them their “meanness,” realizing that I owed them gratitude for their passionate, selfless devotion to the school and our education.

We had pored over the map of Latvia—that clog-shaped puzzle piece in Europe’s northeastern corner—year after year, as our shoe sizes grew bigger. To us, Latvia seemed as remote as the Moon. Several times we listened to the story about Ivan the Terrible and the massacres in Vidzeme during the Livonian War in the 16th century.

“Along the road from Rīga to Tartu not a rooster crows, not a dog barks.” The chronicler (Matsey) Strykovsky described it with these words: “I myself have seen Latvians burying their dead accompanied by the blowing of horns, as they sing, ‘Go, unfortunate one, from the world of misery into eternal happiness, where you will no longer suffer at the hand of the pompous German, the vicious Lithuanian, and the Muscovite.’ An English traveler (…) paints a descriptive image of this time: “Alas, this terrible, inhumane massacre, drowning, and burning! Women and girls are caught, stripped in the freezing cold, and then in threes and fours tied to horses’ tails and dragged alive or dead along roads and streets. Everywhere lie corpses, old people, children—some wealthy, dressed in velvet and silk, their jewels, gold, and pearls hidden. These people—the most beautiful in the world on account of their origin and climate—now lie cold and frozen. Many have been sent to Russia. It is impossible to calculate the wealth in money, goods, and possessions that are being sent out of the cities and countryside and from 600 plundered and sacked churches.” (Dr. N. Vīksniņš. Latvijas vēsture jaunā gaismā. Oak Park, Illinois: Krolla Kultūras biroja izdevums/Draugas Publishers, 1968, pp. 112–113. Tr. RL)

We took our final exams, graduated, and grew up. Zinta married our Latvian camp’s tennis coach and moved to Canada. Maijroze moved to California and back again. Marty turned into a serious man who drove a BMW and a shiny black Porsche, owned a nice house with a pool in northern Jersey, had two kids, and supported our Latvian school and camp. Many of my peers did not take to Latvian indoctrination well. The school felt like prison. Also, conservative Latvian society scared some people away. It is not easy to live in two parallel cultures. To get rid of the discomfort, many chose to block out one of two competing identities. Unfortunately, in many cases the Latvian identity was sacrificed.