Читать книгу Skylarks and Rebels - Rita Laima - Страница 18

A Latvian Folk Tale about Ezere

ОглавлениеSeveral centuries have passed since that time when Ezere Manor was ruled by Baron von Nolcken. Back then it was simply called Nolcken. There was a terrace on the manor house’s east side, where each morning the baron would sit and drink coffee. From the terrace the river, the Vadakste, which formed the border (between Latvia and Lithuania—RL), was well visible. The baron was a ruthless sadist. Beneath the manor, where the baron often dined with guests, he had constructed a maze of passages. These passages connected the manor house with the chapel and the river, which had once been deep and navigable by ships. It was said that these passages had been dug by slaves. Long, deep, and gloomy, they were filled with dangerous traps. According to the baron’s instructions, secret cellars had been constructed beneath the passages to entrap hapless wanderers.

One such passage was located right beneath the terrace. While the baron entertained his guests on the terrace, beneath it people sentenced to death for minor transgressions stumbled about trying to find a way out. At a certain point in the passage a large millstone had been set into the floor. If someone stepped on the stone, it tipped, propelling the victims into a dark and damp cellar filled with the bones of other victims.

The newlywed wife of the baron’s son, the beautiful Ezere, fell into this trap, too. The young baron and Ezere had just celebrated their wedding. They and other young couples were playing the traditional game of hide-and-seek. Unsuspecting Ezere stepped on the millstone and fell into the cellar. But she was a sorceress. Outraged by what she discovered, she woke up the dead. They emerged above ground, chasing off the evil baron, and Ezere became ruler of the manor. That is how it came to be known as Ezere. (Latvian historical folk tale. Source: http://www.ezere.lv/35550/vesture1. Tr. RL)

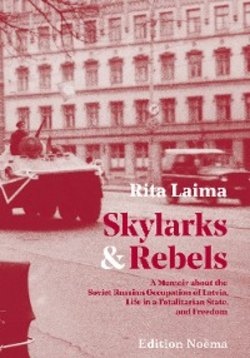

Lielezere Manor. Source: © J. Sedols, Wikipedia. https://lv.wikipedia.or g/wiki/Att%C4%93ls:Ezeres_mui%C5%BEas_pils_2000-11-04.jpg (© CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)

Ghost stories are attached to many of Latvia’s old German manor houses, which remind me of the mansions of the American South. For some reason many of them feature a lady “in green” (zaļā dāma). Was there any truth to the Ezere tale? Had there once been a sadistic baron, a serial killer who had turned his manor into a house of horrors? Baron von Toll must have had a cruel streak in him as well, ordering his subordinates to roll a humongous boulder for ten years from the river to his park. Many of the old manor houses of the Baltic German landed gentry still stand in Latvia, some of them particularly ghostly in their state of neglect or abandonment.

Latvia, land of lore, boasts countless legendary “sacred” springs associated with tales of pagan worship and sacrifice. Our many castle hills inspired tales of mysterious passages and vanishing people and animals. Latvian peasants with lots of time to kill during the long, cold, dark winters spun yarns near the fire about hedgehogs becoming kings and orphans meeting God disguised as a beggar…

Groves of straight birch trees sweep the Baltic sky like gentle brushes. In the spring many Latvians tap into the sap, fermenting it for thirst-quenching, hangover-healing consumption after celebrating the summer solstice in late June. Ancient oak trees of enormous girth rise from the meadows and fields, their massive limbs and fingers providing a perch for birds, shaking down acorns in the fall for wildlife to feed on. Linden trees burst into fragrant bloom in early summer, attracting bees and other pollinators as well as humans in search of fragrant, healthy herbal teas. Latvia’s magnificent forests are full of wildlife; its mysterios bogs beckon with shiny cranberries. If our planet Earth’s biodiversity has diminished severely in the last half-century, then in Latvia it seems to be flourishing. According to Yale University’s 2012 Environmental Performance Index, Latvia was ranked the second cleanest country in the world. Paradoxically, the backwardness of the Soviet economy and agricultural system just may have contributed to Latvia’s “cleanness” and its high ecological rating. Most of Latvia’s lakes are clean and full of fish.

My son Jurģis photographed at our house in northern Latvia with toys he made from acorns. (Photo by Andris Krieviņš)

What kinds of creatures call Latvia’s open spaces and forests home? My people have whimsical dainas and folk songs about moose, elk, deer, bears, wolves, foxes, the gorgeous lynx, wild boar, polecats or fitchews, the hare, ermines, weasels, red squirrels with their cute tufted ears, flying squirrels, hedgehogs, badgers, otters, seals, and other animals, birds, fish, insects, and snakes, including the venomous odze (adder). The now extinct auroch or wild ox (taurs) and wisent or European bison (sūbris, sumbrs) once roamed across Latvia. Each summer storks from Africa visit Latvia to build their nests on chimneys and telephone poles; their clattering can be heard from far away. People in Latvia are close to nature, because they spend a lot of time outdoors sowing, planting, and harvesting. In the early 1990s wolves attacked and ate our beloved dog, Duksis… Latvia was a bit wild back then and still is.

Latvia is also a former battleground where men of various armies fought and died in many wars. The sounds of the skylark, cuckoo, corncrake, owl, and choruses of insects sang fleeting eulogies. Today it is hard to imagine that Latvia could sustain so much bloodshed, destruction, and human displacement in the conflicts of the previous century. Its quiet forests remind me of the quiet and peace of great cathedrals, and my generation has no personal recollection of these conflicts. Yet war has a way of rippling into the future. We are part of its aftermath. In the 1990s, when I first visited Kurzeme, I was enraptured by its beauty and sobered by thoughts of the war, the streams of refugees, and the tragedy of Latvia in the 20th century.

Ärmelband "Kurland," 1945. (“Army Group Courland Cuff Title.”) Source: Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File:%C3%84rmelband_Kurland.jpg (© Public Domain)

Latvia’s highest mountain, Gaiziņš, which rises a mere 312 meters above sea level in the central part of Vidzeme, is more like a hill. The first time I climbed up its slope in the summer, I giggled. This was it? Our famous Gaiziņš “mountain”? However, the view from the top was breathtaking. Latvia’s countryside provides no points of dramatic beauty like the Swiss Alps or New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Its beauty is soft, a verdant velvet of rolling hills, forests, meadowlands, fields of ripening grain, and blue lakes that reflect a bright blue northern sky. Dusty roads cut through the scenic landscape dotted with old wooden buildings.

Lovely lakes, some quite deep like Dridzis in Latgale (65.1 meters), and smaller waterways add sparkle to the green landscape. Two large rivers wind through Latvia: the Daugava (“river full of souls”), emerging from the east in Russia and Belarus and flowing into the Gulf of Rīga near the Latvian capital; and the Gauja, which unfurls in the central part of the region of Vidzeme, loops northwards and then snakes south, depositing its waters into the gulf as well. Living in Rīga, the Daugava became a part of my life; I walked across it many times, always admiring the reflection of Rīga’s centuries-old skyline. The only other city to occupy such a meaningful place in my identity is New York.

Latvia continues to change. with each generation encountering a new set of problems and challenges. My family’s history reflects that of its country. My grandparents were born at the turn of the 20th century, when Latvia was still part of Tsarist Russia. They grew up against a backdrop of dramatic historical events and completed their higher education in the newly independent Republic of Latvia. As communist Russia underwent tumultuous and bloody changes that transformed it into an even more dangerous, unpredictable neighbor, my grandparents started careers and families in the exciting years of free and independent Latvia. That brief 20-year period of independence was marked by the rapid dismantling of an old and unjust political system based on centuries of Baltic German minority rule, the redistribution of land, the rebuilding of Latvia’s industry, which had been destroyed by World War I, and the steady growth of wealth, stability, and international recognition. But Latvia’s independence, bought with blood, would be short-lived.

Four generations in Olaine, Latvia in 1984: on the wall a portrait of my great-great-grandfather Jānis Rumpēters (1831–1915); my paternal grandmother Emma (born Lejiņa) Rumpētere; my son Krišjānis and I. (Photo by Andris Krieviņš)

The Latvian economy has changed over time. Agriculture continues to play a big part in the life of Latvians, and farming seems to be second nature to them. As elsewhere, the Industrial Revolution would bring enormous changes, as new industries and factories attracted laborers from the countryside to the city. Then World War I razed much of Latvia’s industry, mostly concentrated in Rīga, but there was an incredible resurgence and a rebuilding effort in the brief years of independence between the two wars. Forestry remains a precious resource and export for Latvia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, most Soviet era industrial plants, including those based on Latvia’s pre-war industry (such as VEF―Valsts Elektrotechniskā fabrika), were privatized, split up, and sold off, with the loss of thousands of manufacturing jobs. Today Latvia’s farmers struggle to compete within the European Union’s vast agricultural market, proving that each era brings a new set of challenges for my people to deal with.

Latvia has been a democratic parliamentary republic since 1991 and joined the European Union in 2004. Like many countries that once fell under the Soviet sphere of influence, it has deep-rooted problems, such as corruption, financial crime, a lagging economy, weak governmental oversight, and regional disparity.

There are wonderful positives about Latvia: its status as the 2nd cleanest country in the world; its status as the most beautiful country in the world (according to the Daily Mail of the United Kingdom, May 14, 2012, and other sources); the success of its cultural endeavors, including world class choirs (Kamēr, Balsis, The State Academic Choir Latvija) and opera singers of international fame (Elīna Garanča, Maija Kovaļevska, Kristīne Opolais, and others); its brilliant conductors (Mariss Jansons, Andris Nelsons), etc. Famous violinist Gidon Kremer grew up and went to music school in Rīga. Ballet legend Mikhail Baryshnikov was born and raised in Rīga. Latvia’s artists regularly participate in the world’s biennales. The music of Pēteris Vasks (b. 1946), Ēriks Ešenvalds (b. 1977), and other Latvian composers can be heard on American classical radio stations. Vasks’ wife Dzintra Geka has made a name for herself promulgating via film and books the tragic stories of the children of Latvia deported to Siberia. In 2014 Rīga was the European Capital of Culture.

“Latvia/Baltic recognition” has improved in the United States in recent years. In 2011–2012 it was in the international financial news for its “successful” “austerity” measures. Over the years Latvia has been mentioned in film and on TV in mostly humorous references to an obscure European country, such as: the “Latvian Orthodox Church” episode on “Seinfeld”; the Latvian sneaker “Teslick” episode on “Family Guy”; etc. Latvia’s problems have also propelled it into the news, such as the collapse of the Maxima department store in Rīga in 2013, which killed more than 50 people. However, when Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945, they were largely forgotten by the world.

My son Tālivaldis working on a batch of gingerbread cookies.

A small but resilient nation, it is miraculous that after all that Latvians have been through, we can still come together to sing, dance, and be merry. Wearing our traditional folk costumes, we are proud of our rich cultural heritage. I remain an idealist, even as modern-day Latvia struggles with its post-Soviet woes. Hopefully, things will improve. Recuperating from 50 years of foreign occupation and influence has been very difficult for many Eastern European countries.

I invite you, my reader, to visit my beautiful ancestral country Latvia, as well as its Baltic neighbors, Lithuania and Estonia. Good food and lovely cities, towns, countrysides, and unique monuments to fascinating histories and cultures await you. My sons and other members of my extended family live there, as do many dear friends. Latvia needs people; its schools need children; its cemeteries where our ancestors lie must be taken care of. Those of us who hail from Latvia must ask ourselves this question: who will take care of Latvia, if not us?

A winter wonderland… My first real “taste” of the beautiful Latvian countryside was in Piebalga, an area historically known for its artisans and writers. (Photo by Andris Krieviņš)