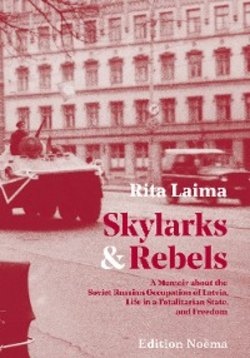

Читать книгу Skylarks and Rebels - Rita Laima - Страница 22

Catskill Summers

ОглавлениеLatvian Camp Nometne, 1974: your truly winning a race. Family photo.

When I was little, we spent our family summer vacations at the Jersey shore. I can still remember the feel of the hot sand grasping my little feet and dragging me down, the scent of the ocean’s salty spray, and tar baking in the hot sun. When we got older, my parents packed us off to Latvian “Nometne” (“camp”) in the beautiful Catskill Mountains. The trip was a nightmare for me, as I inevitably ended up vomiting in the back of the car or by the side of the road. With the introduction of Coca Cola and Dramamine into my life, these awful bouts of nausea ceased. Nometne filled me with excitement, anxiety, and even dread: would I have friends?

For our parents Latvian camp was a godsend. They could deposit us in a place where speaking Latvian was the rule, and where we would be occupied all day long for two to four weeks at a time. Who wants their kids at home in the suburbs in the summer, bored out of their minds? With Latvian school in the winter and Latvian camp in the summer, they had us “covered.” Our parents hoped that camp would deepen our exposure to Latvian values, culture, the Lutheran faith, and lasting friendships. There was the added bonus of a gorgeous natural setting: tall, forested mountains; fields where Latvian kids could run around in the fresh air and sunshine; a lake fed by a mountain stream; and hide-and-seek and treasure hunts in the pristine woods around us. Evening candlelight services by the lake or up in the lovely debesspļavas (“Fields of Heaven”) nurtured our spirituality.

The camp kitchen run by Latvian moms provided great meals. Sports were interspersed with Bible studies, art, music, song, dance, theater, and great hiking excursions. We began our mornings by raising the American and Latvian flags and singing an uplifting chorale. The sound of our young voices floated up and out into the beautiful valley between the mountains. We gazed at the mysterious lookout tower on Spruce Top, where our neighbors, German Americans, had established an exclusive residential club in the late 19th century. The words of many of these chorales have stayed with me: “Rīta gaisma mūžīga, / Atspīdums no Dieva vaiga, / Tavu staru spožumā / Izzūd tumsas vara baiga! / Tavu spēku liec mums just, / Naktij zust. (“Eternal morning sun, / Reflected from God’s brow, / In your brilliant rays / Night’s terror wanes! / Let us feel your power, / Let night fade.” (K. Rosenrot, 17th century. Tr. RL) It was nice to start the day with a song.

While eating a breakfast of oatmeal of a glue-like consistency with cinnamon or the more preferable pancakes with sticky syrup, I would often gaze at Ēvalds Dajevskis’ (1914–1990) fantastic painting of an ancient Latvian fortress on the Daugava River. Its dramatic orange sunset hues bathed the ancient scene in suspense and drama. And wasn’t it so, that my people’s history was full of suspense, drama, and never-ending conflict? Dajevskis’ art was archetypal for Latvians, and in it we recognized ourselves.

In the Catskills summers were cooler with none of the awful humidity of New Jersey. These mountains were also popular with New York’s Hasidic Jews who fondly called them Borscht Belt or the Jewish Alps. Sometimes we saw them walking along the roads outside of Tannersville. The streams that cut through the camp’s territory seemed clean enough to drink from; on the weekends, as we waited for our parents to arrive, we hopped from rock to rock, studying the small pools in search of tiny fish.

Gvīdo, Andris, Ēriks, Pēters, Vidvuds, Andris, Aldis… We giggled, gawked, sighed, and blushed, and hoped to dance with our crushes. We stole glances at them, as we paraded around to Chopin’s Polonaise. Our parents hoped that we would marry Latvians. They were uncomfortable with the idea that we might stray outside our Latvian bubble. They came to our balles and sat in the corner staring and smiling. It made us uncomfortable and even angry.

Nometne ran like a clock: we were responsible for keeping our cabins in order and clean, and we took turns sweeping and mopping the camp’s facilities with PineSol and setting and clearing our tables at meal times. Campers were split into teams that competed against each other in sports and other activities. We chatted in English amongst ourselves but switched to Latvian around the counselors and managers. There were two main camp rules: “Runājiet latviski!” (“Speak Latvian!”) and “Akmeņi nelido!” (“Rocks don’t fly!”).

Not everyone had sweet memories of Latvian camp. One summer, when my older brother was about 15, he begged our parents to take him home after his friends left camp. Some of the new camp arrivals were reputed to be bullies, and my brother suddenly felt very much alone. Our parents refused. They had signed him up for a month, and he was going to stay, no “ifs, ands, or buts.” Shortly after our parents left, my brother famously “escaped” from camp, walking the 3.5 miles to to Tannersville, where he boarded a bus to New York City. He showed up on our block in Glen Ridge in the evening, striding past our house, too afraid to ring at the door. My mother, who had been alerted to the fact by the camp director and my grandfather (who was vacationing on the camp property), recalls standing in the veranda at dusk watching her son walk by, her heart breaking. When it got dark, he came to the door and rang the bell. As mother and son hugged, he said, “I told you I wasn’t going to stay at camp!” The pain and guilt of this incident stayed with my mother for years: she blamed herself for inflexibility and insensitivity. “We were so obsessed with this Latvian thing!” she lamented more than 40 years later.