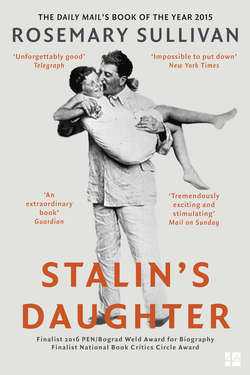

Читать книгу Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva - Rosemary Sullivan - Страница 13

Chapter 2 A Motherless Child

ОглавлениеNadya with a young Svetlana, c. 1926.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

During the afternoon of November 7, 1932, Svetlana stood with her mother at the front of the crowd watching the soldiers march past the Hall of Columns to honor the fifteenth anniversary of the Great Revolution. This was the first time she had been allowed to attend the annual celebrations. It was an extraordinary festival, with stilt walkers, fire-eaters, and circus performers moving into and out of the throng of thousands of people. She looked up at her father on the platform where his giant image hung behind the Party magnates lined up dutifully on either side of the vozhd. She was only six and a half, but she understood that her father was the most important man in the world.

Earlier that day, her mother had called her into her room. “I saw my mother so rarely that I remember our last meeting very well.” Svetlana sat on her favorite takhta and listened as her mother delivered a long lesson on manners and deportment. “Never drink wine!” she said.1 Nadya and Stalin always quarreled when he dipped his finger into his wine and put it into his children’s mouths. She protested that he would turn her children into alcoholics. Her final words to Svetlana were in character. Nadya dismissed as self-indulgence the emotional effusiveness that she associated with her mother, Olga; and her sister, Anna. Crying, confessions, complaining, and even frankness were not in her repertoire. The most important thing was to do one’s duty and to hide one’s secrets in the small square over one’s heart.

As her nanny put her to bed, Svetlana recounted how Uncle Voroshilov led the whole parade riding on a white horse.

On the morning of November 9, Alexandra Andreevna got the children up early and sent them out to play in the dark, rainy dawn. When they were bundled into a car hours later, the staff all seemed to be crying. They were driven to the new dacha at Sokolovka. Stalin had begun to indulge his penchant for building dachas, and that fall the family was using the Sokolovka dacha instead of Zubalovo. The house was gloomy, with a dark interior that seldom got any light. The children knew something was terribly wrong and kept asking where their mother was. Eventually Voroshilov arrived to take them back to Moscow. He was in tears. Their father seemed to have disappeared.

So many apocryphal stories have gathered around what had happened the previous night that it is impossible to sort fact from fiction, gossip from truth, but a rough outline of the night can be reconstructed.

In the late afternoon of November 8, Nadya was in the apartment in the Poteshny Palace preparing for the inevitably boisterous party to celebrate the Revolution. Her brother Pavel, currently stationed in Berlin as the military representative with the Soviet trade mission, was visiting and had brought her gifts, one of which was a lovely black dress. The Kremlin wives always complained that when they met Nadya at the fashionable Commissariat of Internal Affairs dressmaker on Kuznetsky Bridge, reserved for the Party elite, she selected the most drab and uninteresting clothes. They were amused that she was still following the outdated Bolshevik ethic of modesty.2 That night, in her elegant black dress, she was beautiful; she had even placed a red rose in her black hair.

Accompanied by her sister, Anna, Nadya crossed the snowy lane to the Horse Guards building and entered the apartment of Comrade Voroshilov, the defense commissar, who was hosting the anniversary celebration for the Party magnates and their wives. Stalin sauntered down the lane from his office at the Yellow Palace in the company of Comrade Molotov and his chief of economics, Comrade Valerian Kuibyshev. They had only one or two guards with them, though the Politburo had banned the vozhd from “walking around town on foot.”3 The Politburio had concluded that Stalin was no longer safe, so hated were the policies of terror he had already adopted against so-called industrial saboteurs, bourgeois experts, and political terrorists conspiring with foreign powers. Assassination seemed a real possibility.

For everyone this was an occasion to unwind. The food arrived from the Kremlin kitchen—an ample spread of hors d’oeuvres, fish, and meat, with vodka and Georgian wine—served by the housekeeper. The men, many still sporting the tunics and boots that were a throwback to their revolutionary past, and the women in their designer dresses, sat at the banquet table. Stalin sat in his usual spot in the middle of the table, across from Nadya. This was a hard-drinking, exuberant lot, ready to down toast after toast to the old revolutionary triumphs and the new industrial achievements.

In the anecdotal reports in the multiple memoirs left behind by those present at the party that night, stories coalesce around the following details. Stalin was drunk and was flirting boorishly with Galina, a film actress and the wife of the Red Army commander Alexander Yegorov, by lobbing bread balls at her. Nadya was either disgusted or simply tired of all this. There had been gossip about Stalin’s current dalliance, with a Kremlin hairdresser. Stalin liked to confine his philandering to those from whom discretion could be ensured, and a hairdresser working at the Kremlin would have belonged to the secret police. Nadya had seen it all before and knew these affairs never lasted, though neither she nor anyone else seemed to know how far they went. Years later Stalin’s bodyguard Vlasik made the suggestive comment to Svetlana that her father “was a man after all.”4 That night, Nadya was seen dancing coquettishly with her Georgian godfather, Abel Enukidze, then administrator of the Kremlin complex, a usual stratagem for an angry woman to demonstrate her studied indifference to her husband’s flirtations.

Many accounts claim that it was a political toast that inflamed Nadya. Stalin toasted “the destruction of enemies of the state” and noticed that Nadya did not raise her glass. He shouted across the table, “Hey you, why aren’t you drinking? Have a drink!”5

She replied venomously, “My name is not hey,” before storming out of the room. The revelers could hear her shouting over her shoulder, “Shut up! Shut up!” as she exited. The room fell silent in shock. Not even a wife would dare turn her back on Stalin. Stalin only muttered contemptuously, “What a fool,” and kept on drinking.

Nadya’s close friend Polina Molotov rushed out after her. According to Polina, she and Nadya circled the Kremlin a number of times as Polina reminded her of how much pressure Stalin was under. He was drunk, which was rare: he was just unwinding. Polina said Nadya was “perfectly calm” when they said good night in the early hours of the morning.6

When Nadya returned to the Kremlin apartment, she entered her room and closed the door. After fourteen years of marriage, she and Stalin slept separately. Her room was down a hall off to the right from the dining room. Stalin’s room was to the left of the dining room. The children’s rooms were down another hall, and much farther down that hallway came the servants’ rooms.

Sometime in the early hours of the morning, Nadya took the small Mauser pistol that her brother Pavel had given her as a gift and shot herself in the heart.7

Nobody seems to have heard the shot—certainly not the children and none of the servants. In those days, the guard stood outside at the gate. Stalin, if he was home, seems to have slept through it all.

The housekeeper, Carolina Til, prepared Nadya’s breakfast, as she did every morning. She claimed that when she entered the room, she found Nadya lying on the floor beside her bed in a pool of blood, the little Mauser pistol still in her hand. Til ran to the nursery to wake Svetlana’s nanny, Alexandra Andreevna, and together they went back to Nadya’s room. The two women laid Nadya’s body on the bed. Rather than call Stalin, whose anticipated reaction terrified them, they phoned Nadya’s godfather, Abel Enukidze, and then Polina Molotov. The group waited. Finally Stalin woke and entered the dining room. They turned to him: “Joseph, Nadya is no longer with us.”8

Rumors would later surface that, after the party, Stalin had gone to the Zubalovo dacha with another woman and had arrived home in the wee hours of the morning. He and Nadya quarreled, and he’d shot her. Stalin was a kind of magnet for vengeful myths, but this one is unlikely. More convincing is the relatives’ certainty that Nadya committed suicide, and they were angry: how could she abandon her children like that?

They also claimed Nadya left a bitter and accusatory suicide note for Stalin, though supposedly he destroyed it immediately upon reading it. Pavel’s wife, Zhenya, reported that for the first few days, Stalin was in a state of shock. “He said he didn’t want to go on living either. . . . [Stalin] was in such a state that they were afraid to leave him alone. He had sporadic fits of rage.”9

Nadya and Stalin together at a picnic, from a photo taken in the early 1920s.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

The family needed to believe that he was devastated, and it is possible that he was. He had, in his way, loved Nadya, as his love letters to her attest. Even dictators can be sentimental. But his reaction was cruelly egocentric and focused on himself. Stalin’s sister-in-law, Maria Svanidze, recorded in her private diary the moment when she told Stalin that she blamed Nadya: “How could Nadya have left two children?” He responded, “The children have forgotten her after a few days, but I am left incapacitated for the rest of my life.”10 It is hard to imagine a father saying this of his grieving children, but Stalin’s self-pity seems convincing. Svetlana always believed, more realistically, that her mother’s suicide exacerbated Stalin’s paranoia: No one could ever be trusted; even those closest betrayed.

Why did Nadya, just thirty-one, kill herself? We will never know the truth, but speculations abound. The easiest explanation is that she was mentally ill. Initially, even Svetlana believed this. The historian Simon Sebag Montefiore writes: “[Nadya’s] medical report, preserved by Stalin in his archive, and the testimonies of those who knew her, confirm that Nadya suffered from a serious mental illness, perhaps hereditary manic depression or borderline personality disorder though her daughter called it ‘schizophrenia,’ and a disease of the skull that gave her migraines.” Nadya suffered multiple other ailments. She had had several abortions, a not uncommon form of contraception in those days, which resulted in a number of gynecological problems.11 She retreated to spas and German health resorts, an indulgence, indeed almost a fetish, of most of the Party elite.

But eventually Svetlana came to see her mother’s despair as motivated by her opposition to Stalin’s repressive policies. The question is whether there is any credibility to this idea.

Nikita Khrushchev, her fellow student at the Industrial Academy, claimed Nadya tried to assert her independence from Stalin.12 When she registered at the Academy in 1928, she retained her own name, Alliluyeva, though in truth this was not unusual among Bolshevik wives. She refused to travel to the Academy in a government car and rode the tram; this was why she had a pistol. Her brother Pavel had brought back two Mauser No. 1 pistols from a trip to England, giving one to Nadya and one to Molotov’s wife, Polina. Alexander Alliluyev, Pavel’s son, would later remark, “They took the tram to their school, and there was some real danger at that time in Moscow. Because of that, my father brought those two damned pistols from England. And in regards to this, Stalin said to my father, ‘You couldn’t find another gift?’ The gun had tiny bullets, but they were enough for Nadya to shoot herself in the heart.”13

From her correspondence as a teenager, it is easy to see Nadya as a dogmatic, idealistic young Communist. During the Civil War that raged after the Bolsheviks’ triumph, she seemed able to rationalize the violence as necessary to the survival of the Great Revolution. When, in June 1918, Lenin sent Stalin south to Tsaritsyn (renamed Stalingrad in 1925) with 450 Red Guards to secure food supplies for Moscow and Petrograd, the seventeen-year-old Nadya and her brother Fyodor accompanied him as his assistants. A railway carriage was pulled to a siding, and Stalin used it as his headquarters. They hadn’t yet registered their marriage, but under Bolshevik convention, Nadya was already considered Stalin’s wife.

Immediately Stalin began to purge the city of suspected counterrevolutionaries. When he wrote repeatedly to Lenin demanding sweeping military powers, Nadya typed his letters. When Lenin ordered him to be ever more “ruthless” and “merciless,” Stalin replied, “Be assured that our hand will not tremble.”14

Stalin conducted a campaign of “exemplary terror.” He burned villages to show the consequences of failure to comply with the Red Army’s orders and to demonstrate what counterrevolutionary sabotage would lead to. His enthusiasm for indiscriminate violence did not seem to faze Nadya, typing away in her railway carriage.

Nadya loved Stalin and seemed comfortable rationalizing, indeed even glamorizing, the Bolshevik cult of violence. The passionate love letters they sent each other when they were apart had an electric, if conventional, intensity. As late as June 1930, when Nadya was in Carlsbad talking a cure for debilitating headaches (another report suggests that she was actually suffering acute abdominal pains, possibly from an abortion), Stalin wrote: “Tatka [his pet Georgian name for her]. Do write to me something. . . . It is very lonely here, Tatochka. Am sitting at home, alone, like a little owl. I have not been to the country—too much work. I have finished my own task. I plan to go the day after tomorrow to the country, to the children. Well, good-bye. Do not stay there for too long, come back soon. I—kiss—you. Yours, Josef.”15 One of her letters to him ended: “I beg you to take good care of yourself. I kiss you warmly, as you had kissed me at my leaving. Yours, Nadya.”16

But domestic life with Stalin had a different tenor and was extremely volatile. Nadya made a first attempt to leave him in 1926, when Svetlana was only six months old. After a quarrel, she packed up Svetlana, Vasili, and Svetlana’s nanny and took the train to Leningrad (as Saint Petersburg was renamed in 1924 after Lenin’s death), where she made it clear to her parents that she was leaving Stalin and intended to make her own life. He telephoned and begged her to come back. When he offered to come to get her, she replied, “I’ll come back myself. It’ll cost the state too much for you to come here.”17

Perhaps Stalin’s worst characteristic as a husband was the tantalizing quality of his affection. With her pride and reticence, Nadya rarely revealed family secrets, but her sister Anna remarked that she was a “long-suffering martyr.” Stalin, usually distant and inscrutable, could flare up with an uncontrollable temper and could be callously indifferent to his wife’s feelings. Nadya complained that she was always running Stalin’s errands—he needed a document in the commissar’s office; he needed a book from the library. “We wait for him, but never know when he will come home.”18

Nadya’s second year at the Industrial Academy, 1929, was the Year of the Great Turn and the forced collectivization of the peasantry into kolkhozy, or collective farms. The process was brutal. In order to root out private enterprise, village markets were shut down and livestock was confiscated. Kulaks, or prosperous peasants (owning one cow could constitute prosperity), were deported. Under this policy, known as dekulakization, peasants, “treated like livestock . . . often died in transit because of cold, starvation, beatings in the convoys, and other miseries.”19 By the year of Nadya’s death, 1932, the infamous Gulag (forced-labor camps) held “more than a quarter of a million people,” and 1.3 million, “mainly deported kulaks,” were living as “special settlers.”20

In 1932 and 1933, famine raged in the Ukraine. Stalin and his ministers were shipping grain supplies abroad to pay for smelters and tractors in order to sustain the rapid pace of industrialization. Though the Ukraine Politburo begged for emergency relief, no assistance came. Millions died. In 1932, a number of Nadya’s fellow students at the Industrial Academy were arrested for speaking out about the famine. Nadya, too, was rumored to oppose “collectivisation and its immorality.” Critical of Stalin, she secretly sympathized with Nikolai Bukharin and the right-wing opposition.21 Stalin commanded Nadya to stay away from the Academy for two months.22

In the early days, Nadya attempted to exert some influence. When Stalin was vacationing alone in Sochi in September 1929, Nadya wrote him a careful letter, reporting that the Party was exploding over a dispute at Pravda; an article had been published without first being cleared by the Party hierarchy. Though many had seen the article, everyone was laying the blame on her friend Leonid Kovalev, and demanding his dismissal. In a long letter with the simple salutation “Dear Josef,” she wrote:

Don’t be angry with me, but seriously I felt pain for Kovalev, for I know the colossal work that he has done in the paper. . . . To dismiss Kovalev . . . is simply monstrous. . . . Kovalev looks like a dead man. . . . I know that you detest my interference, but still I believe that you should look into this absolutely unjust outcome. . . . I cannot be indifferent about the fate of such a good worker and comrade of mine. . . . Good-bye, now, I kiss you tenderly. Please, answer me.23

Stalin wrote back four days later: “Tatka! Got your letter regarding Kovalev. . . . I believe you are right. . . . Obviously, in Kovalev they have found a scapegoat. I will do all I can, if it is not too late. . . . I kiss my Tatka many, many, many times. Yours, Josef.”24 Stalin did act on Nadya’s request and wrote to Sergo Ordzhonikidze, in charge of adjudicating cases of disobedience to Party policies, to say that scapegoating Kovalev was “a very cheap but wrong and unbolshevik method of correcting one’s faults. . . . Kovalev . . . IN NO CIRCUMSTANCES WOULD EVER let one line about Leningrad be printed, had it not been silently or directly approved, by somebody at the bureau.”25 Kovalev was eventually dismissed from Pravda—not as an “enemy of the people” but rather as “a straying son of the Party.”26

Nadya wrote back rather pathetically: “I am very glad that in Kovalev’s matter you have shown me your trust” and went on to report that the Academy was very friendly. “The academic achievements are judged according to rules: ‘kulak,’ the ‘center,’ the ‘poor one.’ We laugh a lot daily about that. I am already characterized as a right-wing,” a strange admission to make to Stalin who would soon destroy the so-called right-wing opposition.27

There were clearly mounting tensions between Nadya and Stalin. She wrote in the summer of 1930, “This summer I did not feel that you might be pleased with a postponing of my departure, quite the contrary. The last summer I did feel that, but not now. . . . Answer me, if not too displeased by my letter, or rather, as you wish.”28 He wrote back to say that her reproaches were “unjust.”29 In October she wrote, “No news from you. . . . Maybe hunting quails absorbed you too much, or just too lazy to write.”30 Stalin responded with irony: “Lately you have begun to praise me. What does that mean? Good or bad news?”31 Nadya’s letters to Stalin in Sochi often contained reports of the hunger in Moscow, the long lines for food, the lack of fuel, the disrepair of the city. “Moscow looks better now, but in some places like a woman who covered with powder her defects, especially after rains, when the paint runs in stripes. . . . One wishes so that these shortcomings would one day leave our lives, and people would then feel wonderful and work remarkably well.”32

By the time of her suicide, it is possible that Nadya was not schizophrenic but rather disillusioned with her husband’s revolutionary politics. The night of her death, she refused to raise her glass in Stalin’s toast to “the destruction of enemies of the state.”

Nadya’s friend Irina Gogua, who had known her since their shared childhood in Georgia, when the Alliluyev children, having no bathroom in their own apartment, had come for weekly Saturday baths at her house, remembered how Nadya behaved in Stalin’s presence.

[Nadya] understood a lot. When I returned [to Moscow], I understood that her friends were arrested somewhere in Siberia. She . . . demanded to see their case. So she understood a lot. . . . In the presence of Joseph she resembled a fakir, who performs in the circus barefoot walking over broken glass. With a smile for the audience and with a terrifying intensity in her eyes. This is what she was like in the presence of Joseph, because she never knew what was coming next—what kind of explosion—he was a real cad. The only creature who softened him was Svetlana.

Gogua was not surprised when she heard the gossip that Nadya had committed suicide. Though the truth about her suicide was immediately suppressed, Gogua claimed that it was known among the security organizations. She added an interesting detail to her story. “Nadezhda had very perfect features and very beautiful features. But here is the paradox. The fact that she was beautiful was observed only after her death. . . . In the presence of Joseph, she was always like a fakir—always internally tense.”33

As recently as 2011, Alexander Alliluyev, the son of Nadya’s brother Pavel, offered a convincing detail in the puzzle of Nadya’s suicide with a piece of the story that came to him from his parents.34

Pavel was at work when he heard the news that his sister had committed suicide. He immediately phoned his wife, Zhenya. He told her to stay where she was; he’d be right home. When he arrived, he asked where she had hidden the packet of papers that Nadya had given them. “In the linen,” Zhenya replied. “Get them,” he told her.

Nadya had been planning to leave Stalin. She intended to go to Leningrad and had even asked Sergei Kirov, head of the Communist Party organization there, about getting a job in the city. In the packet of papers she left with her brother was supposedly a parting letter for him and his wife.

Zhenya kept the existence of the letter secret for two decades and spoke to her son, Alexander, of its contents only in 1954, after Stalin’s death. She told her son that Nadya had written that she “could not live with Stalin anymore. You take him for someone else. But he is a two-faced Janus. He will step over everybody in the world, including you.” Alexander commented, “We all came to know what kind of a person Comrade Stalin was, but at the time, only Nadya knew about this.”

Zhenya asked Pavel what they should do with the letter, and he replied, “Destroy it.” The destruction of the letter and documents, of course, makes it impossible to verify the story, as is the case with so many stories about the inscrutable Stalin.

As an adult, Svetlana always believed that Nadya committed suicide because she had concluded there was no way out. How could one hide from Stalin? Svetlana’s nanny later told her of overhearing Nadya’s conversation with a female friend just days before she committed suicide. Nadya said that “everything bored her, she was sick of everything, and nothing made her happy.” “What about the children?” the friend asked incredulously. “Everything, even the children,” Nadya replied.35 Such boredom was a sign of profound depression, but it was a painful account for her daughter to hear. Her mother had been “too bored.” Svetlana’s responses to her mother would always swing, unresolved, between sentimental idealizations and bitter anger.

Svetlana could not remember how or when she was told of her mother’s death or even who told her. She remembered the formal resting in state that began at 2:30 on November 9. The news of Nadya’s death had been shocking, and hundreds of thousands of Muscovites wanted to say good-bye to her, even though many were hearing her name for the first time. Stalin kept his family life very private.

Nadya’s open coffin rested in the assembly hall at the GUM; a huge building with atria, it housed government offices as well as the GUM department store. Irina Gogua remembered that the lines of people outside were so long that some of the uninitiated public wondered what the stores were giving away.36 Svetlana remembered that Zina, the wife of Uncle Sergo Ordzhonikidze, took her hand and led her up to the coffin, expecting her to kiss her mother’s cold face and say good-bye. Instead she screamed and drew back.37 That image of her mother in her coffin seared itself in her mind, never to be dislodged. She was rushed from the hall.

There are several versions of Stalin’s behavior at the ceremony. In one, he sobbed, and Vasili held his hand and said, “Don’t cry, Papa.” In another, Molotov, Polina’s husband, always recalled the image of Stalin approaching the coffin with tears running down his cheeks. “And he said so sadly, ‘I didn’t save her.’ I heard that and remembered it: ‘I didn’t save her.’”38 In Svetlana’s retelling, Stalin approached the casket and, suddenly incensed, shoved it, saying, “She went away as an enemy.”39 He abruptly turned his back on the body and left. Had Svetlana herself heard this? The anecdote sounds like retrospective invective and does not seem like the observation of a six-year-old in hysterics. Perhaps this was someone else’s story.

A cortege of marching soldiers accompanied the coffin carried on a draped gun carriage covered in flowers. Vasili walked with Stalin beside Nadya’s coffin in the procession to the Novodevichy Cemetery. Svetlana was not present.

Svetlana believed her father never visited her mother’s grave. “Not even once. He couldn’t. He thought my mother had left him as his personal enemy.” Yet there were stories from Stalin’s drivers of secret nocturnal visits to Nadya’s grave site, especially during the coming war.40

Mourners walk alongside Nadya’s coffin during the procession to Novodevichy Cemetery in November 1932. Vasili is the small boy in the front row. Svetlana was not present.

(Meryle Secrest Collection, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University)

Pravda reported Nadya’s death in a perfunctory manner, without explanation. Her suicide was a state secret, though everyone in the apparat knew about it. The children, along with the public, were told another story: Nadya had died of peritonitis after an attack of appendicitis.

It would be ten years before Svetlana learned the truth about her mother’s suicide. Though this might seem astounding, it is entirely credible. The terror that Stalin had begun to spread around him particularly infected those closest to him. Who would dare tell Stalin’s daughter that her mother had committed suicide? Many would be shot simply for knowing the truth. It soon became “bad form” even to mention Nadya’s name.

Stalin was clearly shocked by Nadya’s death, but he got over it. He wrote to his mother:

MARCH 24, 1934

Greetings Mother dear,

I got the jam, the ginger and the chukhcheli [Georgian candy]. The children are very pleased and send you their thanks. I am well, so don’t worry about me. I can endure my destiny. I don’t know whether or not you need money. I’m sending you 500 rubles just in case. . . .

Keep well dear Mother and keep your spirits up. A kiss.

Your son,

Soso

P.S. The children bow to you. After Nadya’s death, my private life has been very hard, but a strong man must always be valiant.41

But for very young children the scars caused by a parent’s death are profound, in part because death is not something their young minds can grasp; they understand only abandonment. Svetlana’s adopted brother, Artyom Sergeev, remembered Svetlana’s seventh birthday party, four months after her mother’s death. Everyone brought birthday presents. Still not sure what death meant, Svetlana asked, “What did Mommy send me from Germany?”42 But she was afraid to sleep alone in the dark.

A childhood friend, seven-year-old Marfa Peshkova, granddaughter of the famous writer Maxim Gorky, remembered visiting Svetlana after Nadya’s death. Svetlana was playing with her dolls. There were scraps of black fabric all over the floor. She was trying to dress her dolls in the black fabric and told Marfa, “It’s Mommy’s dress. Mommy died and I want my dolls to be wearing Mommy’s dress.”43