Читать книгу Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva - Rosemary Sullivan - Страница 16

Chapter 5 The Circle of Secrets and Lies

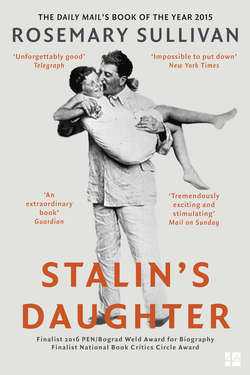

ОглавлениеSvetlana, age eleven, in the uniform scarf of the Soviet youth group Young Pioneers.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

For Svetlana, these were “years of the steady annihilation of everything my mother had created, of systematic elimination of her very spirit.”1 The people whom Svetlana had loved and who had made her childhood secure had been taken away, and she didn’t know why. A wall of silence surrounded things too dangerous to speak of. When Svetlana asked her grandmother what happened to their relatives, Olga said, “It was just something that happened. It was fate.” Her nanny counseled her, “Don’t ask.”2

The family found ways to paper over the horror and carry on—either through denial or by retreating into consoling myths. Though Stalin had personally told Anna Redens that her husband, Stanislav, had been executed, she always insisted that he’d escaped to Siberia. The family continued to spend weekends at Zubalovo. The young people skied or hiked through the forest, a bodyguard always in tow. Anna’s son Leonid recalled a walk that took place when he was eleven years old with his mother, Svetlana, and her nanny and bodyguard. It was early spring. Svetlana, who was three years older, “carefully, bit by bit, slipped away” from the group, taking Leonid with her. They walked for miles beside a small river. At a particularly precipitous point, he lost his footing and fell in. She pulled him out, then removed her jacket and gave it to him. He remembered her kindness. He also thought of this as the first time he realized that she “wanted to jump out of this trap.” When they got home, she was roundly reprimanded for running away from her bodyguard.3

At fourteen, Svetlana was anxious to assert her independence. She wrote to her father suggesting that she was no longer a child: “Hello my dear Father, I will not wait for any more orders from you. I am not little in order to be amused by this.”4 A few weeks later, she wrote again. Oddly, it was as if she’d assumed her mother Nadya’s demanding, coquettish voice. Perhaps this was the only way to get Stalin’s attention.

AUGUST 22, 1940

My dear, dear Papochka,

How do you live? How is your health? Do you miss me and Vasya [Vasili]? No. Paposchka, I miss you terribly. I keep waiting for you and you keep on not coming. I feel with “my liver” that you are trying to trick me again—I refer to a lack of joy—and there’s no directive and you will not come. Ay, yai, yai . . .

Now with Geography, it’s a mess again. Because 5 more republics have been added, there’s more territory, more population, and there’s an increased number of industrial spaces but our textbook is taken from 1938, and especially because we have the economic geography of the USSR, there’s lots of stuff missing from the textbook. . . . There’s a lot of crap in it. . . . Scenes of Sochi, Matsesta, different resorts, and, in general, these images are not needed by anyone. . . .

Papochka, please write me right away because you will forget after, or you will be busy. And by that time, I myself will come. OK. I kiss you deeply my dear Papochka. Until we see each other again.

Yours,

Svetlana 5

How would Stalin have responded to his lippy fourteen-year-old daughter criticizing her textbook as full of crap? Unsurprisingly, Stalin was a misogynist. On one occasion, Svetlana overheard her father and Vasili discussing women. Vasili said he preferred a woman with conversation. “My father roared with laughter: ‘Look at him, so he wants a woman with ideas! Hah! We have known that kind: herrings with ideas—skin and bones.’”6 Was he talking about her mother? The remark cut deeply enough that she never forgot it.

Svetlana was turning into an intelligent young woman. At school she loved literature and valued the exotic. Her favorite memory of Zubalovo in her teenage years was of the two yurts that sat on the front lawn at the dacha. Her Uncle Alyosha Svanidze, now dead, had brought them back from a trip he’d made to Guangxi in China. As young teenagers, she and her four cousins—Leonid, Alexander, Sergei, and Vladimir—would sit in those strange dwellings and imagine their inhabitants.

The yurts were round wooden structures made of slats, with walls insulated by patterned felt and floors covered with thick felt rugs. In each yurt, a bronze Buddha sat in a wooden box positioned on top of a small red chest. The Buddha’s demure smile and mysterious third eye captivated Svetlana. It was the first icon of a god she had ever seen. A half century later, she could describe those yurts to a friend with precision.7

Svetlana’s fascination with other cultures is implicit here, but her father did not share this curiosity. Stalin detested travel; he had no real interest in other cultures and, once in power, left the Soviet Union only twice—for Allied peace conferences. Svetlana was never permitted to travel outside the frame of Sochi and Moscow. She would be twenty-nine (and her father dead) before she visited Leningrad. Though this was the norm for Soviet citizens, it was a deprivation for a curious young mind.

When Svetlana was fifteen, the yurts disappeared, as did her entire world—in one fell swoop.

World War II came suddenly, though not without warning, to the Soviet Union. On June 22, 1941, at 4:00 a.m., Stalin, asleep on his couch at his Kuntsevo dacha, was awakened by a phone call from his chief of staff, Marshal Georgy Zhukov, informing him that German planes were bombing Kiev, Vilnius, Sebastopol, Odessa, and other cities. A total of 147 German divisions had crossed the border and were already proceeding at a fierce pace through the Ukraine.8

For months, Stalin had received reports from British and Soviet intelligence agencies that Hitler was planning to stage an invasion, code-named Operation Barbarossa, on June 22. According to Stepan Mikoyan, Stalin had even been warned again that very midnight. In the presence of Mikoyan’s father and several other Politburo members, Stalin was informed that a defecting German soldier had just been apprehended and was claiming the attack was coming in the morning. But as Mikoyan’s son explained, “Stalin’s attitude to intelligence data reflected his extreme mistrust of people. In his opinion everyone was capable of deceit or treason.” When his agents in the field sent him “alarming reports,” Stalin ordered them recalled and deported to the camps to be “ground into dust.”9

Stalin insisted that Hitler would keep to the nonaggression pact the two leaders had signed in 1939. The USSR would not provoke a war. Privately he knew that the Soviet army was not ready—his purges of the armed forces had cut too deeply. Now the front was in anarchy; Russian troops were in flight, and Stalin was to blame. Hitler had disastrously outmaneuvered him.

On June 29, when the Germans encircled four hundred thousand defending Russian troops and took the city of Minsk in Belarus, giving themselves a direct route to Moscow, Stalin climbed into his car waiting outside the Kremlin and turned to his comrades. “Everything’s lost,” he said. “Lenin left us a great legacy, but we, his heirs, have shit it out our asses.”10 Cursing all the way to Kuntsevo, he announced his resignation. For two days, Stalin kept silent in his dacha. There were rumors of a breakdown, but this is unlikely. More convincing is the idea that Stalin was testing his comrades to see whether his leadership would survive the crisis.11

A contingent of frightened ministers, including Beria, Mikoyan, and Molotov, headed to Kuntsevo to ask him to return to work as head of a new “super–war cabinet.” They couldn’t imagine running the war without Stalin. Anastas Mikoyan explained, “The very name of Stalin was a great force for rousing the morale of the people.”12

On July 3, Stalin addressed the nation with his new title, supreme commander, and declared the coming struggle to be the Great Patriotic War. He exhorted the people to “rally round the Party of Lenin and Stalin.” Stalin was something other now, an Idea, no longer just himself. He warned that, in this “merciless struggle,” all “cowards, deserters, panic-mongers” would be ruthlessly crushed.13

Looking back from adulthood, Svetlana would say that her father refused to admit that Hitler had tricked him. “He considered himself infallible . . . his political flair unmatchable.” After the war was over, she recalled his habit of repeatedly saying, “Ech, together with the Germans we would have been invincible!” And then he would add, “So they thought they could fool Stalin? Just look at them, it’s Stalin they tried to fool!” Svetlana was always appalled when her father spoke of himself in the third person, always amazed that it never occurred to him that “he might fool himself.”14

Even as he attempted to control the war disaster, Stalin took measures to protect his daughter. He asked his sister-in-law, Zhenya, to take the family to his dacha in Sochi. “The war will be long,” he told her. “Lots of blood will be shed. . . . Please take Svetlana southwards.”15

Amazingly, Zhenya refused, saying she had to join her husband (she had hastily remarried after Pavel’s death) and to safeguard her own children. Nobody said no to Stalin. He never forgot or forgave a single betrayal, and he could wait years to exact his revenge, as Zhenya would discover.

Stalin next turned to Nadya’s sister, Anna, for help. Threading through the crowds of untold thousands of evacuees desperately trying to leave Moscow, Anna hustled the anxious little troop of Stalin’s relatives aboard a train heading south to the Black Sea. Anna and her own two sons; her parents, Sergei and Olga; Yakov’s wife, Yulia, and their daughter Gulia; and Svetlana and her nanny squeezed together in bewilderment into a private compartment. Even though her school had been practicing war drills for years—she kept a school photo of her class practicing a gas-mask drill in 1935—now Svetlana discovered the real terror of war, and the racking fear for loved ones left behind.

On June 23, one day after the German invasion, Stalin sent his sons, Yakov and Vasili, and his adopted son, Artyom, to the front. Artyom reported rather cryptically in retrospect:

Jacob and me joined the artillery, and Vasili became a pilot. All of us went to the front—from the first day; Stalin telephoned to have us taken there immediately. It was the only privilege we got from him. There remain several letters from Vasili to his father. In one of them from the front, he asked his father to send him money. A snack bar had opened in his detachment and he wanted a new officer’s uniform. His father replied, “1. As far as I know the rations in the air force are quite sufficient. 2. A Special uniform for Stalin’s son is not on the agenda.” Vasili didn’t get the money.16

The family spent the summer in Sochi. Svetlana’s friend Marfa Peshkova had also been evacuated to Sochi and visited Stalin’s dacha one morning. Svetlana came into the room, looking distraught and, as Marfa reported, said, “I had a very strange dream last night. It was as if I saw a large nest in a tree. There was an eagle in the nest with little babies next to it. And suddenly the eagle takes one of the babies and throws it out of the nest. The baby falls and dies.” And then Svetlana cried. “You know, something terrible has happened to Yasha [the family’s pet name for her brother Yakov].” Her last good-bye to him had been over the telephone, just before he left for the front.17

Not long after her dream, Svetlana picked up the phone and heard her father’s voice on the other end. She asked about Yakov, and Stalin replied, “Yasha has been taken prisoner.” Before she had time to respond, he added, “Don’t say anything to his wife for the time being.” Yulia was sitting anxiously on a nearby couch, scrutinizing Svetlana’s face. Svetlana thought her father was being solicitous and so mumbled to Yulia, “He doesn’t know anything himself.”18 She could not bear to tell her the truth.

Svetlana was devastated by her father’s call. In the last few years, she had become very close to her half brother. Though he was nineteen years older, they would study together in the banya at Zubalovo, spreading their blankets among the fragrant birch branches, curled up with their books.

Stalin’s relationship with his older son had always been poor. According to the family, he bullied Yakov relentlessly, calling him soft and worthless. Stalin disapproved of Yakov’s first marriage, and in despair twenty-year-old Yakov had attempted to shoot himself, but the bullet only grazed his chest. Stalin wrote to Nadya from Sochi: “Convey to Yakov from me that he has acted like a hooligan, applying blackmail and I do not have anything else in common with him,”19 and the story circulated that Stalin had laughed and said, “Ha! He couldn’t even shoot straight.”20 Yakov left for Leningrad and didn’t see his father again for eight years, but Svetlana always defended him. “Yakov’s gentleness and composure were irritating to my father, who was quick-tempered and impetuous even in his later years.”21

After the tragic death of his first child, Yakov’s marriage ended in divorce. Perhaps to reconcile with his father, he left his career as an engineer and entered the Frunze Military Academy in Moscow in 1935. In 1936, he married Yulia Meltzer. Again Stalin did not approve. According to Svetlana, this was because Yulia was Jewish, and her father “never liked Jews, though he wasn’t as blatant about expressing his hatred for them in those days as he was after the war.”22 Their daughter, Gulia, was born in 1938. Summers until the war, they would come to Zubalovo, where Yakov, still desperate for approval, tried to ingratiate himself with his father.

Yakov with his daughter, Gulia, 1939.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

By early September, Sochi was no longer a safe refuge, and the family returned to Moscow. The ravages of the war were already apparent. From the windows of the Kremlin apartment, Svetlana could see a gaping hole on the corner of the Arsenal Building opposite, where a German bomb had hit. Vasili had been in the apartment and had been thrown from the bed as the windows shattered.23 She was terrified to discover that a bomb had fallen on Model School No. 25. Of course, it had already been evacuated. Construction crews were hastily building a bomb shelter inside the subway for the War Cabinet.

After their arrival, Stalin explained to Svetlana that there would be new arrangements: “Yasha’s daughter can stay with you for a while. But it seems that his wife is dishonest. We’ll have to look into it.”24 Svetlana was appalled and had no idea what her father was talking about. How could Yulia be dishonest?

Yulia was arrested and incarcerated in the Lubyanka prison. Was it possible that another family member could disappear like this? When the last wave of family arrests had occurred in 1938, Svetlana had been twelve. Now she was fifteen, but she still did not understand. Who was doing this to her family?

On August 16, Stalin had issued Order 270, condemning all who surrendered or were captured as “traitors to the Motherland.” Wives of captured officers were to be arrested and imprisoned.25 Yakov was a traitor; Yulia must be arrested. There would be no exception made for Stalin’s son.

Meanwhile poor Yulia was held in solitary confinement in the dark bowels of the dreaded Lubyanka. The “investigation” would take a year and a half. As the Germans advanced, she was transferred to a prison in Engels, on the Volga.26 When she was eventually freed, in the spring of 1943, her five-year-old daughter, Gulia, did not recognize her and had to be encouraged to approach her mother. No explanation was ever offered to Yulia for her imprisonment. She was simply told she was free to go. She never spoke to Stalin again.

The news of what had actually happened to Yakov filtered out slowly. One report came from Ivan Sapegin, commanding officer of the 303rd Light Artillery Regiment. When Yakov’s armored division was encircled and overrun at Vitebsk in Belarus on July 12, 1941, the divisional commander had fled the battlefield, but Yakov was separated from his unit and had been taken prisoner.27

Yakov served as a Red Army artillery officer in World War II, and he was captured by the Germans on July 16, 1941.

(Meryle Secrest Collection, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University)

The German command immediately informed Stalin by flash cable of his son’s capture and then used it for propaganda purposes. Pamphlets with a photograph of Yakov in his uniform without belt or epaulets, surrounded by German officers, were dropped on Soviet troops.

Stalin’s son, Yakov Dzhugashvili, full lieutenant, battery commander, has surrendered. That such an important Soviet officer has surrendered proves beyond doubt that all resistance to the German army is completely pointless. So stop fighting and come over to us.28

Yakov languished in various POW camps until the spring of 1943, when, after their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad, the Germans attempted to exchange him for Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus. Stalin refused the prisoner exchange. That spring Yakov either was shot or committed suicide; it would never be known which. It would be several years before Svetlana knew her brother’s fate. In this she was like millions of her fellow Soviets.

With the Germans on Moscow’s doorstep and an invasion of the city imminent, the town of Kuibyshev to the southeast was chosen to be the alternative capital. In early October 1941, government personnel, foreign diplomatic missions, and cultural institutions began a hasty evacuation. Lenin’s mummified body had already been removed from its mausoleum and sent by secret train to Tyumen in Siberia.

As Moscow filled with smoke from the bonfires of burning archives, the Stalin family’s belongings were packed into a van. Most of the family was already in Kuibyshev, but it wasn’t yet clear whether Stalin would evacuate too, though it was assumed he would. The Kuntsevo dacha was booby-trapped, and a secret train to transport Stalin stood waiting at a railway siding.

In Kuibyshev, a small local museum on Pioneer Street was emptied of its exhibits and newly painted to house the Stalin family, along with bodyguards, cooks, and waiters. Svetlana’s nanny came with her, as did Mikhail Klimov, her personal “secret police watch-dog,” as she called him. Vasili’s young wife, Galina (they had married in 1940, when Vasili was nineteen), was there. While Grandmother Olga came, Grandfather Sergei had decided he would return to Tbilisi and spent most of the war in Georgia. At Svetlana’s urging, Yakov’s baby daughter, Gulia, was soon permitted to join them.

Stalin elected to stay in Moscow to conduct the war. Svetlana wrote to her father from Kuibyshev on September 19, 1941.

My dear Papochka my dear happiness. Hello.

How do you live my dear Secretary? I am fine here. In our school there are other kids from Moscow. There are many of us so I am not bored.

I only miss you . . . now especially I want to see you. If you allow me, I could fly on a plane there for two or three days. . . .

Recently a daughter of Malenkov and the son of Bulganin . . . left for Moscow, so if they can fly why can’t I? They are the same age as me and in general they are in no way better than I am. . . .

I don’t like the city very much. . . . There are many, and I don’t know why, people who are blind. . . . Every 5th person is a disabled man. Very many poor people and urchins. In Kuibyshev during the war, many people came from Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Odessa and other cities and the locals treat the incomers with an anger they don’t hide. . . .

And now Hitler will come and will bomb this place. . . . Papa, why do the Germans keep coming and coming? When will they finally get a kick in the neck? After all we cannot give up all our industrial areas.

Papa, I have one more request for you. Yasha’s [Yakov’s] daughter Galechka [Gulia] is right now in Sochi. . . . I would very much like for Galechka to be brought to me here. Now she has no one. . . .

Dear Papa . . . I wait for your permission to take a flight to Moscow. But only for two days . . . I don’t know when you are free and that’s why I don’t call. . . . I kiss you many many times once again.

Svetanka 29

The fifteen-year-old Svetlana was by turns petulant, begging, naive, and then, finally, generous. She was a daughter fearful for her father so far away and in danger, a daughter with expectations: she must be flown to see him. On October 28, Stalin gave her permission to travel to Moscow. It was the day the Bolshoi Theater, the university buildings on Mokhovaya Street, and the Central Committee building on Staraya Ploshchad (Old Square) were bombed. She found her father in his bomb shelter, reached by an elevator descending ninety feet into the ground. The commissars had exactly replicated his rooms at Kuntsevo, lining the walls with wood paneling, though now they were covered in maps. The same dining room table had been installed for his dinner guests, who were the same men, but now uniformed officers. The table was also covered with maps, and telephone lines snaked through the rooms. Stalin was constantly in contact with the front. Svetlana was, of course, in the way.

As millions starved in the cities under siege, life in Kuibyshev often had a strange, surreal normalcy. Musicians who had been evacuated from Moscow formed a philharmonic orchestra, and there were concerts. Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony was premiered in Kuibyshev and broadcast around the world. The war was a shadow presence. Health centers and most of the city’s hospital facilities were turned into base hospitals as the wounded arrived with devastating injuries.

A makeshift cinema had been constructed in the ex-museum next to the kitchen, and there everyone watched the newsreels from the front. The cameramen were in the trenches and accompanied the advancing tanks. Svetlana watched battles on the outskirts of Moscow. She soon lost her naïveté about the meaning of war.

That spring in Kuibyshev, Svetlana made a devastating discovery that she claimed shattered her life. Her father had instructed her to keep up with her English language skills now that Britain and the United States were Russia’s allies, and so she had taken to reading any English or American magazine she could lay her hands on. She read Life, Fortune, Time, and the Illustrated London News. One day that spring (she had just turned sixteen), she came across an article about her father. It mentioned, “not as news but as a fact well known to everyone,” that his wife, Nadezhda Sergeyevna Alliluyeva, had killed herself on the night of November 8, 1932.”30

The shock of this revelation was heart-stopping. Svetlana rushed to her grandmother, article in hand, and demanded to know if her mother had committed suicide and why this had been hidden from her. Olga replied that, yes, it was true. Nadya had had a small gun. It had been a gift from Pavel. Olga kept repeating, “Who would have thought it?”

Marfa Peshkova remembered Svetlana showing her the magazine with the article. “I remember this very well. She showed me this photograph. It was a photograph of her mother lying in the coffin. She had never seen this. And somewhere . . . she did not know for sure about the death of her mother. It was rumored then that she died from appendicitis, from a failed operation or something like that. For her it was a shock.”31

When Svetlana had read the article, she hadn’t wanted to believe it, but her grandmother had confirmed it. Her mother had killed herself. Only she, her daughter, seemed not to know. Her anger at her mother’s betrayal of her must have been profound. And she turned that anger on her father. She knew how he could be. She had seen him become mean, even brutal. She was certain it was his cruelty that had caused her mother to commit suicide. Now she began to switch her allegiance to the memory of her mother, but like all orphans of suicides, she would need decades to forgive Nadya for abandoning her.

Things that had been mysterious before suddenly became clear. When her father had said to her over the phone, “Don’t say anything to Yulia for the time being,” it hadn’t been solicitude he was expressing. It was suspicion. The idea of Yulia and Yakov betraying their country was inconceivable. Svetlana began the slow process of realizing that her father was capable of condemning innocent people to prison and even to death.

She would look back and say, “The whole thing nearly drove me out of my mind. Something in me was destroyed. I was no longer able to obey the word and will of my father and defer to his opinions without question.”32 This is the voice of an adult, but certainly Svetlana’s adolescent confusion must have been overwhelming. Which was more devastating: her belief that her father was responsible for her mother’s death or her discovery that her mother had not loved her enough not to kill herself?

Everywhere—at home, at school—her father was called the wise, truthful leader. Stalin’s name was linked to winning the war. He was the great Stalin. Only he could save Russia. To doubt him was an act of blasphemy. But Svetlana had begun to doubt.