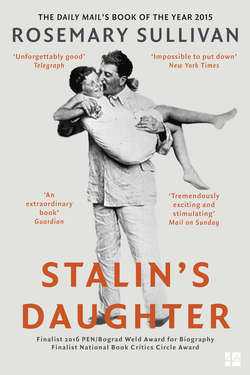

Читать книгу Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva - Rosemary Sullivan - Страница 19

Chapter 8 The Anti-Cosmopolitan Campaign

ОглавлениеBy the end of the 1940s, Stalin had turned on many of the relatives who had celebrated his birthday with him in 1934. Top row, left: Anna Redens was arrested in 1948 (her husband, Stanislav, had been executed in 1940). Middle row: Maria Svanidze (left) was executed in 1942; although Sashiko Svanidze (third from left) survived, her sister Mariko was executed in 1942; Polina Molotov (at Stalin’s left) was arrested in 1948. Bottom row, second from left: Zhenya Alliluyeva was arrested in 1947.

(Courtesy of RGASPI [Russian State Archive of Social and Political History], Fund 558, Inventory 11, Doc 1653, p. 23)

After the war, everyone in the Soviet Union expected an easing of restrictions. The Great Patriotic War had been won at immense cost and through heroic sacrifice. So much reconstruction had to be undertaken. Surely now the long-promised era of socialist plenty was at hand. Instead, a new wave of repression was about to begin. With the cult of personality he’d fostered, Stalin had consolidated his power and assumed the template of the dictator. His adopted son, Artyom Sergeev, remembered an incident during which he heard Stalin upbraiding his son Vasili for exploiting the Stalin name.

“But I am a Stalin too,” Vasili had said.

“No, you’re not,” replied Stalin. “You’re not Stalin and I’m not Stalin. Stalin is Soviet power. Stalin is what he is in the newspapers and the portraits, not you, no not even me!”1

Power, its preservation and execution, had filled the vacuum of a human being. Stalin was an idea now, infallible. And he was still fighting a war. Propaganda made it clear that the Soviet Union had enemies out to destroy it.

It was Winston Churchill who inserted the term Iron Curtain into the public imagination. On March 5, 1946, in a gymnasium at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, Churchill declaimed: “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.”2 Americans, who still thought of Stalin as Uncle Joe, believed Churchill was meddling. But their attitude would soon change.

Within a year after the end of World War II, the Cold War was under way, dividing the world into capitalist and communist spheres. In the background loomed the terrifying threat of the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima. Stalin was now sure the United States intended to attack the Soviet Union sooner or later. In 1946, he placed the meticulous bureaucrat Lavrenty Beria in charge of atomic research. Highly restricted fenced-off settlements for Soviet scientists were constructed in remote regions. Well-trained Soviet spymasters soon brought Stalin the atomic secrets he wanted.3 The first Soviet atom bomb was detonated in 1949.

Even as the playing field of atomic war was being leveled, suspicions between the two countries had grown exponentially since 1946. In 1947, President Truman signed the National Security Act establishing the Central Intelligence Agency. By early 1948, the CIA had already helped to swing an election in Italy away from the Communists.4 Now the deadly game of international intelligence gathering was afoot.

The CIA spied on its own citizens in a domestic campaign of fear. Beginning as early as 1945, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) began hunting for Soviet spies and Communist sympathizers. Senator Joseph McCarthy created paranoia with his reckless Red Scare propaganda, and his sensationalized public hearings targeted thousands of Americans. But Stalin went much further. He turned his secret police, the MGB (Ministry of State Security), even more murderously against his own people. To instill and then control through fear had always been his strategy, and as he had learned from the earliest days, he had to keep the fear going. His solution was to engineer a campaign of ideological purification that became known as the Anti-Cosmopolitan Campaign. All contacts with the West and Western culture were declared subversive. To be seen engaging in any conversation or transaction with any foreigners was forbidden; to seek to marry a foreigner was a crime. Foreign travel was restricted to high Party officials or those accompanied by “handlers.” A shroud of silence blanketed the country. No one dared to express criticism of the Great Stalin, who had won the war. As Sergei Pavlovich Alliluyev put it, “It was not done by anyone. It just wasn’t accepted, nor was it possible.”5

By late 1947, the new wave of repression hit the Stalin family. At five p.m. on December 10, Zhenya, Pavel Alliluyev’s widow, now forty-nine and remarried, was at home in her apartment in the House on the Embankment. She was busy with her dressmaker, sewing a new dress to celebrate the New Year. Zhenya’s married daughter Kyra, twenty-seven, was visiting and was in the dining room rehearsing Chekhov’s The Proposal with her theater friends. Zhenya’s sons—Sergei, nineteen; and Alexander, sixteen—were also there, as was her frail mother, who lived with them. The doorbell rang. Kyra answered it. Two military men, Colonel Maslennikov and Major Gordeyev, stood at the door. “Is Eugenia Aleksandrovna at home?” they asked. “Yes, come in,” Kyra replied and went back to rehearsing the play. Then Kyra heard her mother say, “Prison and bad luck are two things that you can’t avoid.”6

They took Zhenya away in what she was wearing. Hastily kissing her children good-bye, she told them not to worry since she “had no guilt of any sort.” Other agents arrived; their search of the flat lasted well into the night. As they tapped the potted plants, Kyra asked, “What are you looking for? An underground passage into the Kremlin?” But irony was never a good idea with the NKGB. Anyone who came to the flat that evening was ordered to sit and wait. The agents took away all family photos with Stalin and Svetlana and Vasili in them, as well as all autographed books.7

Transported to Vladimir Prison, Zhenya was accused of spying; of poisoning her husband, Pavel, who had died of a heart attack nine years earlier; and of interactions with foreigners. She was kept in solitary confinement. Her children were not permitted to contact her.

Zhenya confessed to all the accusations. She later told her daughter, “You sign anything there, just to be left alone and not tortured!” In prison, bombarded by the screams of victims begging for death, she swallowed glass. She lived, but suffered the consequences in stomach problems for the rest of her life.8

The nighttime arrest had been so surreal that the fear kicked in only later. Alexander Alliluyev remembered that his brother Sergei would lie in bed, waiting breathlessly to hear whether the elevator stopped on their floor. Rustlings or other sounds on the staircase would cause him to tremble. A few weeks later, at about six in the evening, the elevator did stop. Kyra was visiting, as, of course, the secret police knew. She was sitting reading War and Peace. When she answered the knock on the door, it was the commandants again. Her brothers stood behind her to protect her. As the agents read Kyra the arrest warrant, her grandmother cried. “Grandmother, don’t humiliate yourself, don’t cry, you mustn’t,” Kyra remembered saying.9

Kyra was taken to a waiting car. As they drove across Moscow and she watched the streets disappear behind her, she wondered if she would ever see her city again. The journey across the nocturnal city took place in oppressive silence until the heavy gates of the Lubyanka prison swung open and the car drove into the courtyard. She remained stoic until they took everything from her and put her in a cell. Then she wept.

Her interrogator accused her of spreading rumors about Nadya’s suicide. She was dumbfounded. She didn’t know that Nadya had committed suicide. She had always believed the story about appendicitis. “I belonged to the kind of family where it wasn’t accepted to talk more than necessary. There was no gossip. . . . They needed something to accuse us of, so that was what they pinned on me: I was supposed to have talked to everybody.”10

She was kept in solitary confinement for six months. Her salvation was her memory. It was vital to hold on to the belief that a real world still existed outside the walls of that madhouse. She visualized all the movies and musicals she knew. She was permitted to read. She paced her cell, asking herself what she had done. She had always been a good Pioneer, a good Komsomolka. She could not understand. It had to be Lavrenty Beria, who had always had it in for her family.

My only clue was that I was a relative of Stalin and I knew that Beria was bound to say something to Stalin that he would believe. My mother was very outspoken, she was freedom-loving, she was forthright with Stalin and equally truthful with Beria. He had evidently taken a dislike to her from the moment they set eyes on each other. I realized that all this had to be instigated by Beria. Stalin by this time was deeply under his influence.11

People advised Kyra to write to Stalin from prison, but she refused. It was better not to remind Stalin of her existence. But so twisted was her (and indeed most people’s) logic in this climate of fear that she could still rationalize, indeed justify, Stalin’s motives. Her brother Alexander explained:

We could only surmise there must be some minor guilt, something to do with purely personal relationships and loyalty to Stalin. We definitely thought that without Stalin’s knowledge this arrest simply could not have taken place. And so far as he decided on such an extreme thing as to arrest his own close relatives, so, thought we, there must be a reason. It was a cruel step from our point of view. But from his point of view it had to be a legitimate one.12

Zhenya’s second husband, N. V. Molochnikov, a Jewish engineer, was soon arrested. When Zhenya’s sons asked what they were to tell friends about the absence of their mother and stepfather, the NKGB instructed them to say, “Our parents are on a prolonged trip.” “But until what time?” they asked. “Until a special announcement.”13 A number of Kyra’s friends were also arrested.

On January 28, 1948, they came for Svetlana’s aunt Anna, who was Nadya’s older sister and the widow of Stanislav Redens. Her sons—Vladimir, twelve; and Leonid, nineteen—were in the apartment. Everyone was asleep. A colonel, followed by a number of agents, knocked on the door at 3:00 a.m. They showed Anna the arrest warrant. As she was being taken away, Anna said, “What a strange array of misfortunes come upon our family Alliluyev.” The children sat up with their nanny as the search was under way. In their memory it lasted a day and a night.14

Accused of slandering Stalin, Anna Redens was arrested in 1948 and was not released until 1954.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Anna was accused of slandering Stalin. Her interrogators had collected denunciations from family, friends, and acquaintances. However, when they demanded that she sign a confession, her son Vladimir claimed she refused. He said proudly, “When they arrested my mother, they couldn’t get her to sign anything, not even by force. She was stubborn, they couldn’t break her, even by putting her into solitary.”15

In 1993, forty-five years later, when the files of former prisoners were opened to families, Vladimir Alliluyev was permitted to examine his mother’s rehabilitation file, P-212.16 The final dimension of the tragedy was that Zhenya and Kyra had been forced to sign condemnations of Anna.

The House on the Embankment earned a new nickname: The House of Preliminary Detention. (The Russian acronym DOPR is the same for both.) It was now a ghost house as Zhenya’s and Anna’s children drew together for comfort. Uncle Fyodor, Nadya’s brother, lived in the same complex and visited often. “Everyone was shocked—shocked, depressed, surprised. But we all kept holding together, as we always had done, and even more so now,” recalled Leonid, Anna Alliluyeva’s son.17

Svetlana tried to intercede with her father. When she asked him what her aunts and cousin had done wrong, he replied, “They talked a lot. They knew too much and they talked too much. And it helped our enemies.” Everyone was required to shun the families of people who were purged, and they hadn’t done this. When she protested, he threatened: “You yourself make anti-Soviet statements.”18

Zhenya’s son Alexander remembered meeting Svetlana on the Stone Bridge that winter. They both understood that it was too dangerous to speak openly. Alexander’s maternal grandmother had warned him: “Do not write to the freckled one.” They met occasionally, surreptitiously, at the skating rink amid the spruce trees.19

Grandmother Olga was still living alone in the Kremlin, where she would sit brooding over the fate of her four children. Her older son, Pavel, and her younger daughter, Nadya, were dead. Her second son, Fyodor, was mentally disabled, living a half life as a consequence of trauma suffered in 1918 during the Civil War. And her older daughter, Anna, was in prison. Olga couldn’t comprehend why Stalin put Anna in prison. She would give Svetlana letters for Stalin, appealing for her daughter’s release, and then would take the letters back. What was the point?

After the arrests, the grandchildren were soon banned from visiting the Kremlin, so Olga would go every weekend to visit them in their apartments in the House on the Embankment. To Olga it was very clear that Stalin was responsible for their mothers’ imprisonment. Zhenya’s son Sergei remembered her visits in those days. “Grandma would refer to the place where our mothers were confined as nothing other than the Gestapo, although she didn’t say it to Stalin’s face. She knew what that word was about! Her dark humour! She knew things; she had no illusions. She was not far from the truth, either, as we all realized later.”20

Grandfather Sergei had died in 1945. Luckily, he did not live to witness the arrest of his elder daughter, in his memory the child who had once carried live ammunition for the revolutionary cause and refused to wash her hand for a whole day after Lenin had shaken it. But Sergei’s ideals had died long before he did.

Despite Grandmother Olga’s comments, the family chose to focus their anger on Lavrenty Beria. Someone had to be targeting them. It must be Beria carrying tales of their disloyalty and perfidy to Stalin.

Beria was a Mingrelian from Western Georgia. The family believed he had sought the death of Anna’s husband, Stanislav Redens, in 1938 because Redens knew secrets about his past.21 Ten years later, they still believed he was out to destroy them. But however much Beria might have inflamed Stalin’s paranoia, Stalin was always in control. Rather than looking into the utter blackness and the erasure of all trust that locating the blame squarely on Stalin would have involved, the family held to their illusions. Zhenya’s son Sergei Alliluyev admitted that it made things easier. It was “simpler to explain everything this way.” Alexander Alliluyev said, “It is a natural protection.” To repress a terrible idea “keeps one from going completely mad, from losing one’s mind.”22

Looking back, Sergei would add, “What was so terrible for the country in the thirties and the forties is that when they started arresting people here and people there, people began to get used to this, as if this were normal. That is what was so horrible! Everybody believed that this was what had to be.”23

In the meantime, Stalin was bent on a larger campaign, which took all his attention. The Anti-Cosmopolitan Campaign was evolving into the gradual and methodical elimination of Jewish influence on the country’s social, political, and cultural life.

Stalin was particularly incensed by the Jewish Antifascist Committee (JAC), created in 1942 and headed by Solomon Mikhoels, the director of Moscow’s State Jewish Theater. Then it had served as a good propaganda tool to gain the support of American Jews and tens of millions of dollars in financial aid, but now it was evidencing “bourgeois nationalism” in seeking to promote Jewish national and cultural identity.24

On the night of January 12, 1948, Solomon Mikhoels was killed. Svetlana claimed to have been a witness to the murder. She overheard her father on the phone:

One day, in father’s dacha, during one of my rare meetings with him, I entered his room when he was speaking to someone on the telephone. Something was being reported to him and he was listening. Then, as a summary of the conversation, he said: “Well, it’s an automobile accident.” I remember so well the way he said it: not a question but an answer, an assertion. He wasn’t asking; he was suggesting: “an automobile accident.” When he got through, he greeted me; and a little later he said: “Mikhoels was killed in an automobile accident.”

When Svetlana went to her classes at the university the next day, a friend, whose father worked with the Jewish Theater, was weeping. The newspapers were reporting that Solomon Mikhoels died in an “automobile accident.” But Svetlana knew otherwise.

[Mikhoels] had been murdered and there had been no accident. “Automobile accident” was the official version, the cover-up suggested by my father when the black deed had been reported to him. My head began to throb. I knew all too well my father’s obsession with “Zionist” plots around every corner. It was not difficult to guess why this particular crime had been reported directly to him.25

Mikhoels had been sent to the town of Minsk in Belarus to review a play that was being considered for the Stalin Prize. He checked in at his hotel. The next morning, street workers discovered his battered body dumped in a snowdrift. There was no investigation, no effort to explain why Mikhoels might have been outside his hotel in the middle of the night or how such a deadly car crash could have occurred on a quiet back street in the city of Minsk.26 In an elaborately staged public funeral, Mikhoels’s body lay in state at Moscow’s State Jewish Theater for a full day as mourners filed past. But many remained unimpressed by the sham ceremonial send-off of one of the Soviet Union’s most famous directors and actors.

Ironically, for strategic reasons, Stalin’s was one of the first governments to recognize the state of Israel, in May 1948, and that fall he welcomed Golda Meir, the Israeli ambassador to the USSR. Stalin was hoping that the new Jewish state would take a pro-Soviet stance, but when Israel leaned toward America, he was furious. Thousands had greeted Golda Meir that May when she attended a synagogue in Moscow on Rosh Hashanah.27 It was clear to Stalin that Russian Jews who enthusiastically supported Israel were dangerous Zionists. They had friends and family ties in the United States. If war with America broke out, they would betray the USSR.

Articles began to appear in Pravda and Kultura i zhizn in 1948 accusing literary, music, and theater critics, most of whom were Jewish, of “ideological sabotage.” They were branded as “rootless cosmopolitans.” They were “persons without identity,” and “passportless wanderers.”28 Jews were disloyal by definition. Jews resisted the Soviet project of complete assimilation of national ethnicities. They identified themselves as Jews. In 1952, twelve members of the JAC would be executed.

Unwittingly, Svetlana played a minor role in this intrigue. Knowing he was a target, Solomon Mikhoels had, months before his murder, sought information about Svetlana and Grigori Morozov, hoping that the Jewish Morozov might intercede with his father-in-law to cool the virulent anti-Semitic campaign that was emerging in Moscow. This unforgivable approach to his own family confirmed Stalin’s resolve to eliminate Mikhoels. The crime was specific: “Mikhoels conspired with American and Zionist intelligence circles to gather information about the leader of the Soviet government.”29

In late 1948, Joseph Morozov, the father of Svetlana’s ex-husband, was arrested. When Svetlana discovered this and went to her father to appeal for the old man’s release, Stalin was furious. “That first husband of yours was thrown your way by the Zionists,” he again told her. “‘Papa,’ I tried to object, ‘the younger ones couldn’t care less about Zionism.’ ‘No! You don’t understand,’ was the sharp answer. ‘The entire older generation is contaminated with Zionism and now they’re teaching the young people too.’”30

But when it came to her family, her father’s motives were personal.

Trying to defend her aunt Zhenya, Svetlana wrote her father a strange letter on December 1, 1945:

Papochka

In regards to Zhenya and now that the conversation about her has started. It seems to me that these types of doubts came to you because she remarried very quickly and the reason for this she shared with me a little bit. I didn’t ask her myself. I will definitely tell you when you come. If you have doubts like this in another person it is undignified, terrifying, and awkward. In addition it [the problem] is probably not in Zhenya and in her family struggles, but the principal question is—remember that a considerable amount was said about me. And who were they? They can go to hell.

Svetanka 31

We will never be privy to that conversation, but Svetlana seemed to believe that her father was still angry with Zhenya for her hasty remarriage after her husband Pavel’s death in 1938. Rumors circulated, of course, that Zhenya had quickly married to avoid Stalin’s unwanted attentions. She and Stalin had been close. More convincing, however, is the idea that Zhenya’s unseemly haste made her unreliable in Stalin’s eyes. Svetlana assured her father that all was gossip and she could explain.

But it may have been more than this. Stalin was now carefully guarding his reputation, and the aunts “talked too much.” Looking back, Svetlana would conclude, “There is no doubt that [my father] remembered how close they [the aunts] had been to all that happened in our family, that they knew everything about Mamma’s suicide and the letter she had written before her death.”

Svetlana also remembered Zhenya’s description of her father at the outbreak of war in 1941. “‘I had never seen Joseph so crushed and in such confusion,’ was the way she described it. . . . ‘I was even more frightened when I found he was almost in a panic himself.’” Svetlana was certain that her father recalled this. She added with rancor, “He didn’t want others to know about it. And so Yevgenia [Zhenya] Alliluyeva got ten years of solitary confinement.”32 Could the reason for Zhenya’s imprisonment be as simple as the fact that she had seen Stalin in a moment of weakness?

It seems entirely possible that Stalin’s imprisonment of Anna was an act of personal revenge, however. He called Anna “an unprincipled fool . . . this sort of goodness is worse than any wickedness.”33 During the final years of the war, Anna had helped her father, Sergei, to write his memoirs. His carefully self-censored book was published under the title Proydenny put’ (A Traveled Path) in 1946, the year after his death. Meanwhile, Anna had decided to write her own memoirs. When she submitted the manuscript of Reminiscences for official vetting, it was heavily edited by a journalist named Nina Bam and ended safely with the triumph of the Bolsheviks in 1917. It seemed a harmless, moving, personal memoir, but family members were terrified. They begged her not to publish the book. Anna only laughed and said she was working on volume two.

When Reminiscences came out in 1946, it was praised,34 but the family had been right to warn her. In May 1947, a savage review appeared in Pravda, written by Pyotr Fedoseyev and titled “Irresponsible Thinking.” The attack was shocking. Fedoseyev dismissed “memoirs by small people about grand figures with whom they were somehow connected.” Gorky was quoted as lamenting Tolstoy’s experience: “How large, how clingy was the cloud of flies that surrounded the famous writer, and how annoying were some of these parasites who were feeding off his spirit.” Anna was a parasite feeding off Stalin and claiming family intimacy. Official hagiography and encomiums were mandatory, but it was forbidden to write intimately of Stalin. He did not want personal stories obscuring the icon.

But the reviewer, Fedoseyev, had a larger point to make:

It is especially intolerable when authors of such kind attempt to write a memoir about the development of the Bolshevik Party, about the life and the struggle of its outstanding participants. V. Lenin said that the Bolshevik Party was the intelligence, honor, and conscience of our epoch. The history of the Bolshevik Party and the biographies of its leaders embody the historical experience of the struggle for freedom of the proletariat against the capitalist enslavement, for the creation of the fairest, freest way of life on earth. The great achievement of the Bolsheviks and their leaders serves as a source of inspiration for millions of people in their struggle for the complete victory of communist society. During the lessons about the history of the party and its leaders, millions of working people learn how to live and struggle for the interests of society, for the free, joyful, truly human life.

In order to protect the “free, joyful, truly human life” that Soviet society supposedly was, Anna was sentenced to ten years. It is hard to credit, but a large portion of the Soviet population, bombarded by propaganda and cut off from the rest of the world, believed this version of their lives.

The real error of Anna’s memoir, however, was that she didn’t place Stalin at the center of the story. Her portrait of the Revolution was wrong:

The decisive speech made by Comrade Stalin against Lenin’s appearance at the court tribunal against the counterrevolutionaries convinced Lenin to go underground and hide from the provisional government. The short biography of I. V. Stalin expressly states the significance of Stalin’s stance at this time. “Stalin saved Lenin’s precious life for the party, for the people, and for all humanity by decisively taking a stance against Lenin’s appearance at the tribunal and by resisting the suggestions made by the traitors Kamenev, Rukov, and Trotsky” (Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin: Short Biography p. 63). This is the real truth in regard to the question that A. Alliluyeva distorted and twisted in her pseudo-memoirs.35

The reviewer concludes that Anna was “a narcissist,” “an opportunist,” “a self-advertiser” hoping to receive large royalties. Readers were advised to consult the “scientifically constructed” Short Biography of Stalin (written, of course, under Stalin’s supervision) for the truth. Svetlana could see her father’s stock phrases threading the review.36

In retrospect, Svetlana would explain thus: “My father needed . . . to throw out of history, once and for all, those who had been in his way, those who had actually founded and created the Party and had brought about the Revolution.”37 What Anna did wrong was to speak of Stalin as a human being. In his mind, he was already a historical personage.

No such review could have appeared without Stalin’s prior vetting. Anna’s arrest occurred almost a year after the review was published, but this was characteristic of Stalin’s methods. In order to obscure his involvement, he waited patiently for revenge against enemies. The book was banned and Anna disappeared.

Svetlana had seen little of her father during this torturous time, but in early November 1948, while he was on vacation in the south, he summoned her to visit him at his dacha. When she arrived, he seemed angry with her. He called her to the dinner table and “bawled me out,” as she put it, “and called me a ‘parasite’ in front of everyone. He told me ‘no good had come’ of me yet. Everyone was silent and embarrassed.”38 She, too, remained silent. Her father was terrifyingly changeable. The very next day “he suddenly started talking to me for the first time about my mother and the way she died.” It was in fact November 8, the anniversary of Nadya’s death. “I was at a loss,” she recalled. “I had no idea what to say—I was afraid of the subject.”

Stalin was still looking for culprits. “What a miserable little pistol it was,” he remarked. “It was nothing but a toy. Pavlusha brought it to her. A fine thing to give anybody!” Then he remembered how close Nadya had been with Polina Molotov. Polina had been a “bad influence.” He started cursing the novel The Green Hat, which Nadya had been reading shortly before she died. He claimed on several occasions that this “vile book” had distorted her thinking.39

The Green Hat, published in 1924, was a potboiler romance, probably acceptable in Bolshevik circles because it satirized the British upper class. Nadya had been in charge of Stalin’s library and of ordering his books. It is doubtful that Stalin read The Green Hat, but she must have discussed it with him. In the novel, the aristocratic high-minded heroine, betrayed by her lover, commits suicide as a gesture of her contempt for approval from her elite circle. A book did not kill Nadya, but Stalin believed it had an influence on her decision to commit suicide. This similarity paints a portrait of Nadya as a young woman with an icily unbendable pride and a strange sense of idealism.40 In cultural circles in the 1920s, multiple suicides, especially those of the poets Mayakovsky and Yesenin, had made a kind of romanticized cult of suicide. Of course this was only among the intelligentsia. Ordinarily, suicide was looked on as treason against the collective.

Svetlana found the whole conversation with her father utterly painful. She felt he was looking for anything but the real reason for her mother’s suicide—he refused to look at the things that made Nadya’s life with him so unbearable. And she was suddenly frightened. Her father seemed to be speaking to her as an adult for the first time, asking for her trust. “But I’d rather have fallen through the ground than have had that kind of trust.”

That November Svetlana returned with her father to Moscow by train. When the train stopped at the various stations, they’d descend for a stroll. There were no other passengers on the train, and the platforms had been cleared. Stalin strolled to the front engine, chatted with the engineer and the few railway workers who had security clearance, and then got back on the train, seeming not to notice that the whole thing was a “sinister, sad, depressing sight,” as Svetlana saw it. Her father was a prisoner of his own isolation, an isolation he had constructed. Before the train pulled into the Moscow station, it was diverted to a siding, and the two passengers descended. General Vlasik and the bodyguards were there to greet them, puffing and fussing as Stalin cursed them.41

Father and daughter parted, each dissatisfied with the other. It was impossible to be with her father. He had sacrificed everything human in him to the pursuit of power. After seeing him, she always needed days to recover her equilibrium. “I had no feeling left for my father, and after every meeting I was in a hurry to get away.”42 This, however, was not entirely true. Svetlana could never wholly repudiate her father. His black shadow always remained over her, impossible to exorcise. There was the father to be pitied and there was the dictator. She would always believe that in some part of him, the father loved her.