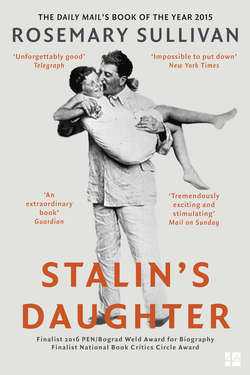

Читать книгу Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva - Rosemary Sullivan - Страница 14

Chapter 3 The Hostess and the Peasant

ОглавлениеStalin with Vasili and an eight-year-old Svetlana.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Svetlana always divided her life into two parts: before and after her mother’s death, when her world changed utterly. Her father immediately decided to move out of the Poteshny Palace, where the shade of Nadya hovered in every corner. Nikolai Bukharin offered to swap his ground-floor apartment in the Kremlin Senate, also known as the Yellow Palace, where Lenin had once had his private residence. Stalin accepted.

The apartment was long and narrow with vaulted ceilings and darkened rooms and had once served as an office. Svetlana hated it. The only familiar object was a photograph of Nadya at Zubalovo, wearing her beautifully embroidered shawl; Stalin had had the picture enlarged and hung in the dining room over the elaborately carved sideboard. Svetlana filled her bedroom with mementos of her mother. Stalin’s office was on the floor above, and the Politburo met in the same building.

Svetlana’s home was now full of vigilant strangers. It was run on a military model with a staff of agents of the OGPU (the secret police) who were called “service personnel” rather than servants. Svetlana felt they treated everyone but her father as nonexistent. She was sure her mother would never have allowed such an invasion, but Stalin obviously thought the quasi-military regimen of the household fitting. His children were not to be spoiled. No luxuries, no indulgences. He probably also thought the security was necessary. Enemies were about.

Even Svetlana’s beloved Zubalovo had altered. When she and Vasili returned there after their mother’s death, she was devastated to find the tree house they called “Robinson Crusoe” dismantled, and the swings gone.1 For security reasons, the sandy roads had been covered with ugly black asphalt, and the beautiful lilacs and cherry bushes had been dug up. While the extended family still frequented Zubalovo on weekends and Grandpa Sergei lived there most of the time, Stalin seldom visited the dacha again.

Grandmother Olga continued to live in a small apartment in another building in the Kremlin. With its Caucasian rugs, its takhta covered with embroidered cushions, and the old chest holding photographs, Olga’s apartment was the only welcoming space in this strange new world. When Svetlana visited, she would find her grandmother raging at the new regimen. She called the “state employees” a waste of public money. The staff retorted that she was “a fussy old freak.”2

Svetlana’s maternal grandmother, Olga Alliluyeva, in an undated photograph.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

It was soon clear that Stalin had no intention of living in the Kremlin. Shortly after Nadya’s death, he had his favorite architect, Miron Merzhanov,3 design him a new dacha in the village of Volynskoye in the district of Kuntsevo, about fifteen miles outside Moscow. He called it Blizhniaia, the “near dacha.” Stalin was said to have chosen this name for its useful vagueness in telephone conversations that might be overheard by enemies. The sixteen-room dacha, painted camouflage green, sat in the center of a forest. To approach it one had to drive down a narrow asphalt road and pass through a sixteen-foot-high fence with searchlights mounted, within which was a second barrier of barbed wire. Svetlana detested her father’s new dacha. She said that the dacha and the Kremlin apartment continued to surface in her nightmares for decades.

By 1934, Stalin had moved to his dacha in Kuntsevo. Most evenings, he came down the stairs of the Yellow Palace to dine at the Kremlin apartment with his children. With him would be members of his inner circle, all men. Svetlana would rush to the dining room. Her father would seat her on his right. As the men talked business, she would stare up at the framed photograph of her mother over the sideboard. Her father would turn to her and ask about her school marks and sign her school daybook. This, at least, was her memory of family dinners. Though she never mentions her brother, presumably Vasili was also there and equally silent. At the end of the meal, Stalin would dismiss his children and continue his discussions with his Politburo members into the small hours of the morning. Then he would head out to Kuntsevo, where he slept. Sometimes he would come upstairs in his overcoat to give his sleeping daughter a good-night kiss.

Stalin’s departure was an elaborate ritual. There would be three identical cars with tinted blue windows waiting outside. Stalin would pick one, climb in, and move off in a cordon of guards, taking a different car and a different route each night. The traffic on the Arbat and Minskoye highways was stopped in four directions. He always waited until the last minute to tell his personal secretary, Alexander Poskrebyshev, or his bodyguard, Nikolai Vlasik, that he intended to leave for his dacha.4

Life at the Kuntsevo dacha also had a military tone, with commandants and bodyguards. Two cooks, a charwoman, chauffeurs, watchmen, gardeners, and the women who waited on Stalin’s table all worked in shifts. They, too, were employees of the OGPU. The commandants and bodyguards, in particular, were high functionaries rewarded for their services with Party privileges: good apartments, dachas, and government cars. Valentina Istomina—everyone, including Svetlana, affectionately called her Valechka—soon joined the household as Stalin’s personal housekeeper and stayed with him for eighteen years. According to Molotov, there were many unconfirmed rumors that she was Stalin’s bed companion.5

Though the nanny Alexandra Andreevna was permitted to stay with Svetlana in the Kremlin apartment, a new governess, Lidia Georgiyevna, arrived in 1933. Svetlana disliked this governess immediately for reprimanding her nanny: “Remember your place, Comrade.” The seven-year-old Svetlana shouted back, “Don’t you dare insult my nanny.”6

With her mother gone, Svetlana’s devastation was palpable, and she directed her neediness toward her father. She spent August 1933 with her nanny in Sochi. There she wrote to her father, who was in Moscow:

AUGUST 5, 1933

Hello my dear Papochka [Daddy],

How are you living and how is your health? I received your letter and I am happy that you allowed me to stay here and wait for you. I was worried that I would leave for Moscow and you would come to Sochi and I would not see you again. Dear Papochka, when you come you will not recognize me. I got really tanned. Every night I hear the howling of the coyotes. I wait for you in Sochi.

I kiss you.

Svetanka7

It had been nine months since her mother’s death. A child, afraid of the dark, listens to the coyotes howling in the woods, worried that her father will disappear. She was seven years old. She waited. This unappeasable emotional hunger would return without warning to sabotage Svetlana throughout her life.

Stalin seems to have been somewhat aware of his young daughter’s psychological needs. Candide Charkviani, a visiting writer and politician whom Stalin admired and promoted, described in his memoirs how shocked he was to discover that “Stalin, someone who absolutely lacked sentimentalism, expressed such untypical gentleness towards his daughter. ‘My little Hostess,’ Stalin would say, and seat Svetlana on his lap and give her kisses. ‘Since she lost her mother I have kept telling her that she is a homemaker,’ Stalin told us.”8

Stalin had loving diminutives for Svetlana. She was his “little butterfly,” “little fly,” “little sparrow.” He developed a game for her, which they continued to play until she was sixteen. Whenever she asked him for something, he would say, “Why are you only asking? Give an order, and I’ll see to it right away.”9 He called her his hostess and told her he was her secretary; she was in charge. He would descend from his office on the upper floor of the Yellow Palace and head down the hall, shouting, “Hostess!”

But this was still Stalin. He also invented an imaginary friend for Svetlana called Lyolka. She was Svetlana’s double, a little girl who was perfect. Her father might say he’d just seen Lyolka and she’d done something marvelous, which Svetanka (the affectionate diminutive Stalin used) should imitate. Or he might draw a picture of Lyolka doing this or that. Secretly, Svetlana hated Lyolka.

When he was staying at his dacha in Sochi, Stalin would write his daughter letters in the big block script of a child, signing them Little Papa:

To My Hostess Svetanka:

You don’t write to your little papa. I think you’ve forgotten him. How is your health? You’re not sick, are you? What are you up to? Have you seen Lyolka? How are your dolls? I thought I’d be getting an order from you soon, but no. Too bad. You’re hurting your little papa’s feelings. Never mind. I kiss you. I am waiting to hear from you.

Little Papa 10

Stalin called himself Secretary No. 1. Svetlana would write short notes to Secretary No. 1 with her orders, and pin these with tacks on the wall near the telephone above his desk. Amusingly, she also sent missives to all the other “little secretaries” in the Kremlin. Government ministers, such as Lazar Kaganovich and Vyacheslav Molotov, had no choice but to play the game.

Svetlana would order her Secretary No. 1 to take her to the theater, to ride the new subway, or to visit the Zubalovo dacha.

OCTOBER 21, 1934

To Comrade J. V. Stalin.

Secretary No. 1

Order No. 4

I order you to take me with you.

Signed: Svetanka, the Hostess

Seal

Signed: Secretary No. 1

I submit. J. Stalin 11

Stalin always spent several months each fall working alone at his southern dacha in Sochi; Svetlana would be left in her nanny’s hands. She would write her father loving letters, but one can hear the solicitude and tentativeness in her tone:

SEPTEMBER 15, 1933

Hello my dear Papochka,

How do you live and how is your health? I arrived well except that my Nanny got really sick on the road. But everything is well now. Papochka, don’t miss me but get better and rest and I will try to study excellently for your happiness. . . .

I kiss you deeply.

Your Svetanka 12

Stalin’s letters could be affectionate and teasing:

APRIL 18, 1935

Hello Little Hostess!

I’m sending you pomegranates, tangerines and some candied fruit. Eat and enjoy them, my little Hostess! I’m not sending any to Vasya [Vasili’s nickname] because he’s still doing badly at school and feeds me nothing but promises. Tell him I don’t believe promises made in words and that I’ll believe Vasya only when he really starts to study, even if his marks are only “good.” I report to you, Comrade Hostess, that I was in Tiflis for one day. I was at my mother’s and I gave her regards from you and Vasya. She is well, more or less, and she gives both of you a big kiss. Well, that’s all right now. I give you a kiss. I’ll see you soon.13

He signed his letters: “From Svetanka-Hostess’s wretched Secretary, the poor peasant J. Stalin.”

There were others who remembered the little “hostess.” Nikita Khrushchev managed to stay in Stalin’s favor after Nadya’s death. He recalled Svetlana as a lovely little girl who was “always dressed smartly in a Ukrainian skirt and an embroidered blouse” and, with her red hair and freckles, looked like “a dressed-up doll.”

Stalin would say: “Well, hostess, entertain the guests,” and she would run out into the kitchen. Stalin explained: “Whenever she gets angry with me, she always says, ‘I’m going out to the kitchen and complain about you to the cook.’ I always plead with her, ‘Spare me! If you complain to the cook, it will be all over with me!’” Then Svetlanka [sic] would say firmly that she would tell on her papa if he ever did anything wrong again.14

The game of the Hostess and the Peasant might have seemed charming, but it had a dark side. Khrushchev claimed that he felt pity for little Svetlana “as I would feel for an orphan. Stalin himself was brutish and inattentive. . . . [Stalin] loved her, but . . . his was the tenderness of a cat for a mouse.”

A British journalist, Eileen Bigland, recalled meeting Svetlana in 1936 when she was a “lumpy schoolgirl” of ten. “Her father adored her. He loved listening to her exploits in the Park of Rest and Culture. He patted her delightedly when she played ‘The Blue Bells of Scotland’ on the piano. He was a rough and tumble father to her, a pincher and a teaser—like a bear with a cub—and you felt at any minute that he might cuff her like a bear. She was a jolly little girl.”15

The Kremlin contained a small cinema on the site of what had once been the Winter Garden, linked by passageways to the Kremlin Senate. After the usual two-hour dinner, which ended at nine p.m., Svetlana would beg her father to let her stay up. He would feign displeasure and then laugh. “You show us how to get there, Hostess. Without you to guide us we’d never find it.”16

It was thrilling for the child to race ahead of the procession through the passageways and out across the grounds of the deserted Kremlin. Behind her followed her father, his cronies, the security guards, and at a distance, the slow-moving armored car that now always accompanied the vozhd. The movies would end at two a.m. When the last film was over, Svetlana would race back through the empty grounds, leaving the men behind to continue their discussions.

Stalin viewed all new Soviet films in the Kremlin before they were released to the public, so the ones Svetlana watched were often Russian: Chapayev, Circus, Volga-Volga. But Stalin loved American Westerns and particularly Charlie Chaplin films, which would send him into fits of laughter—with the exception of Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, which was banned.17 She would always think back nostalgically to these times: “Those are the years that left me with the memory that he loved me and tried to be a father to me and bring me up as best he knew how. All this collapsed when the war came.”18

After her mother’s death, as Svetlana put it, her father became the “final, unquestioned authority for me in everything.”19 None was more brilliant at psychological manipulation than Stalin, the “poor peasant” controlling his little “hostess.” Svetlana would spend a lifetime trying to rip off the mask of compliance that she had invented for her father. She would often succeed, spectacularly, only to find the mask slipping back over her face. A paradox was forming: a child who could order around the most powerful members of the Politburo as her secretaries, but also a dreadfully lonely little girl who learned to behave.

Though it is often said that the family disintegrated after Nadya’s death, the family members refute this. All of them—Grandfather Sergei and Grandmother Olga, Uncle Pavel and Aunt Zhenya, Aunt Anna and Uncle Stanislav, Uncle Alyosha and Aunt Maria Svanidze—continued to visit. For the next two or three years, the Alliluyevs and Svanidzes remained close to Stalin. There were shared trips in the summer to Sochi, and the New Year and birthdays were celebrated at Stalin’s Kuntsevo dacha. According to Svetlana’s cousin Alexander Alliluyev, the family was fragile but united, still absorbing the shock of Nadya’s suicide, all of the relatives asking themselves: “Why did we not see it coming?” Alexander’s father, Pavel, felt particularly guilty about giving his sister that small gun.20

From left: Vasili, future Supreme Soviet chairman Andrei Zhdanov, Svetlana, Stalin, and Svetlana’s half brother Yakov at Stalin’s dacha in Sochi, c. 1934.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

It is even possible that Stalin was keeping up some semblance of family ties. When Svetlana was nine, he arranged for her, Yakov, and Vasili to visit his mother, Keke, in Tiflis. It was 1935, two years before Keke’s death. Though the palace in Tiflis was grand, she continued to live like a peasant in a ground-floor room. The visit was not a success. Keke terrified Svetlana. Sitting up in her black iron cot surrounded by old women dressed in black who looked like crows, she tried to speak to Svetlana in Georgian. Only Yakov spoke Georgian. Svetlana took the candies her grandmother offered her and retreated outside as soon as she could.

Stalin was not on this trip. Before her death, he did manage to visit his mother in her final illness. It was supposedly on this visit that Keke made her famous rebuke to her son. She asked, “Joseph, who exactly are you now?” Stalin answered, “Remember the tsar. Well, I’m like a tsar.” Keke responded, “What a pity you never became a priest.” Svetlana reported that her father always recounted this conversation “with relish.”21

Svetlana was now attending Model School No. 25 on Staropimenovsky Street in the center of Moscow. When she turned seven, Stalin ordered Karl Viktorovich Pauker, in charge of security for Stalin and his children, to check out the best schools.22 Her brother, Vasili, then twelve and in grade five at the less rigorous School No. 20, was transferred to Model School No. 25 to join her. At 7:45 a.m. each weekday, a Kremlin limousine dropped Svetlana and Vasili off at Pushkin Square. They walked the short distance to the school, through the large oak doors, and up the stairs to the second floor, where their father’s and Lenin’s portraits hung on the wall of the imposing landing.

Svetlana’s school years coincided with the cult of personality. Stalin’s image appeared everywhere, and he began to be hailed with grandiose epithets, from the Great Helmsman to Soviet Women’s Best Friend. His relative Maria Svanidze insisted this wasn’t personal vanity. According to her, Stalin claimed that “people need a tsar, that is someone to whom they could bow and in whose name they could live and work.”23 This disclaimer is not entirely convincing, though it would seem that shrewd political calculation about the impact of propaganda, as much as megalomania, motivated Stalin’s cult of personality. In any case, Svetlana climbed the stairs to meet her father’s face every morning.

Because she was used to private tutors, the school was a shock. The first day, she walked into the boys’ bathroom, as she had always done at home among her brothers and cousins, and was ever after known as the girl who walked into the boys’ toilets.24

Svetlana in her classroom at Model School No. 25 in Moscow, sitting at the third desk in the second row, in 1935.

(Meryle Secrest Collection, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University. Courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Model School No. 25 was no ordinary school. It was considered the best in the country. As one former pupil described it, it was “the school where the big-shot children went.”25 So rarefied was the world of Model School No. 25 in relation to what was happening in the rest of the country that it was like stepping through the looking glass. Palms and lemon trees dotted the hallways, and there were white tablecloths on the tables in the cafeteria. The students included the sons and daughters of the famous and powerful: the children of actors, writers, an Arctic explorer, an aviation engineer, members of the Comintern’s Executive Committee and the Politburo, and other high government officials. There were many limousines.

Model School No. 25 was a Soviet lycée with very high scholastic standards. By 1937 the library, with its resplendent banner, WITHOUT KNOWLEDGE, THERE IS NO COMMUNISM, had twelve thousand volumes and subscribed to forty journals and newspapers. Beside the library was a quiet room where children played dominoes, table croquet, and chess.26

The school had clubs in theater, ballroom dancing, literature, photography, airplane and automobile modeling, radio and electrotechnology, parachute jumping, and chess. The boxing club and track club trained on the surrounding streets. There were sports competitions, a rifle team, and volleyball tournaments. A doctor and a dentist were in residence. The children went on excursions to Moscow’s famous Tretyakov Gallery and to Tolstoy’s estate, and they vacationed at sanatoriums on the Black Sea. Even as the train carried them through the famine-stricken Ukraine on their way to their Crimean summer camps in the early 1930s, and though the station platforms were crowded with hungry people begging for food, students remained under the spell of their school. Their teachers did not discuss the famine.

Model School No. 25 was treated as a “shopwindow on socialism,” and thousands, including foreigners, came to visit. Reporters and photographers would follow in their wake. The American singer Paul Robeson placed his son there in 1936, though under an assumed name. When the school needed money, a letter from the director to Stalin or Kaganovich would get a response. One American visitor, Joseph C. Lukes, wrote in the visitors’ book: “The standards of lighting, heating, ventilation and cleanliness are up to American standards.”27 Soon the school got more money to renovate and upgrade. Model School No. 25 was meant to be better than American schools.28

There were schools outside Moscow that the foreigners did not visit, schools where, by the early 1930s, students went without paper (they wrote notes in the margins of old books) and pens were rationed. Because of a shortage of desks, classes were taught in shifts. Schools closed for lack of firewood or of kerosene for lamps. Outside the capital, the devastation caused by forced collectivization and the attacks on the kulaks, which led to widespread famine, meant that often as many as 40 percent of the students dropped out. Many of them had died.29

In 1929, Andrei Bubnov, commissar of enlightenment and head of the Communist Party’s Agitation and Propaganda Department (Agitprop), called upon all schools “to immerse themselves in a class war for the transformation of the Soviet economy and society.” Students and teachers at Model School No. 25 were meant to internalize the Stalinist credo: “a respect for obedience, hierarchy and institutionalized authority; a belief in reason, optimism and progress; recognition of a possible transformation of nature, society, and human beings; and an acceptance of the necessity of violence.”30 Like all Soviet schools, Model School No. 25 promoted indoctrination with banners hung in the hallways: DOWN WITH FASCIST INTERVENTION IN SPAIN or LIFE HAS BECOME BETTER, COMRADES, LIFE HAS BECOME MORE JOYFUL (Stalin’s famous 1935 pronouncement).31

All Soviet children were trained in Communism. First they were Octobrists, then Pioneers, then Komsomols. One became an Octobrist in first grade on November 7 (October in the old, Julian calendar) to coincide with Revolution Day. Everyone got a red star with a white circle in which was the head of baby Lenin.

One became a Pioneer in third grade. Children received triangular red scarves that they were required to wear every day. They also got pioneer pins with the slogan ALWAYS READY! Svetlana proudly wore her Pioneer uniform and marched enthusiastically with the Model School No. 25 contingent in the annual May Day parades across Red Square. “Lenin was our icon, Marx and Engels our apostles—their every word Gospel truth,” she would say in retrospect.32 And it went without saying, her father was right in everything, “without exception.”

However, there was a paradox at the core of the Model School. When Svetlana started there in 1933, only 15 percent of the teachers and administrators belonged to the Communist Party. Many of them had questionable backgrounds as part of the prerevolutionary nobility, the White Army, religious organizations, or the merchant class. Model School No. 25 managed to be relatively democratic and fostered an ideologically unacceptable individualism.33 Some of its graduates became critical opponents of the Communist system, working as reformist editors, historians, attorneys, and human-rights activists.

It is compelling to compare the reputations of Stalin’s children at the school; they were polar opposites. Most of Vasili’s schoolmates remembered him as an amusing and rambunctious boy who was constantly in trouble. His closest friend was called Farm Boy (Kolkhoznik)—the boy’s family had recently migrated from the countryside; his mother scrubbed the school floors.34

Vasili was notorious for his pranks. A church had once stood beside Model School No. 25, and the mounds of graves in its abandoned graveyard were still visible. One of Vasili’s favorite escapades was to sneak into the graveyard with his buddies to dig up bones.35 And he was already known for his cursing. When reprimanded by schoolteachers, he would say he would do better, “remembering whose son I am.”

Still, his fellow students considered themselves his equals. When he broke a window and blamed someone else, they beat him up. When he harassed a boy who had poor eyesight, they voted to expel him from the Komsomol.36 There was an amusing moment when he deliberately interrupted a film being shown to visiting teachers and his instructor shouted, “Stalin, leave the room.” They all froze until they saw the diminutive Vasili storm out. Whenever he attempted to intimidate the administration and teachers with his name, reports were sent to Stalin, who had relayed firm instructions that his children were to be treated like everybody else.37

Vasili was clearly afraid of his father, but he was already presuming on the authority his name conferred. Aged twelve, he wrote to Stalin. He had taken to calling himself Vaska Krasny (Red Vaska), presumably to please him:

AUGUST 5, 1933

Hello Papa.

I got your letter. Thank you. You write me that we could leave for Moscow on the 12th. Papa, I asked the Commandant if he could personally arrange for the wellbeing of the teacher’s wife. But he refused. So the teacher arranged for her to work in the barracks of the workers. . . . Papa, I send you three rocks on which I have painted. We are alive and well and I am studying until we meet again soon.

Vaska Krasny 38

In this instance Vasili’s intervention seems to have been benevolent, but having Stalin’s children in their charge made school officials very nervous. Vasili complained to his father:

SEPTEMBER 26 [NO YEAR]

Hello Papa,

I live well and go to school and life is fun. I play in my school’s first team of soccer, but each time I go to play there’s a lot of talk about the question that without my father’s permission I can’t play. Write to me whether or not I can play and it will be done as you say.

Vaska Krasny 39

Only Svetlana seemed to have measured the cost to Vasili of his mother’s suicide when he was just eleven. She believed Nadya’s disappearance from their lives completely destroyed her brother. He began drinking at the age of thirteen and, when drunk, often turned his venom against his sister. When his foul language and crude sexual stories became too explicit, Yakov, her half brother, would step in to defend her. She later told several interviewers, “My brother provided me with an early sex education of the dirtiest sort.”40 She did not elaborate, but it is clear that she kept Vasili at a safe distance. She said she discovered she loved her brother only after he died.

However, she was grateful for one thing. Svetlana was often ill in childhood, but her father refused to send her to the hospital, presumably for security reasons. She remembered long lonely days exiled to her room in the care of nurses and her nanny.41 But that changed in her adolescence. Saying she was “fat and sickly,” Vasili pushed her into sports. Soon she joined the ski team and the volleyball team and developed the robust health that would characterize her for the rest of her life.

In 1937 Vasili was finally transferred to Moscow’s Special School No. 2, where he continued to trade on his name, refusing to do his homework, throwing spitballs in class, whistling, singing, and walking out. But at his new school, the administrators tried to coat over his lapses and even allowed him to skip his final exams. The German teacher who tried to give him a failing grade was threatened with dismissal. Even as an exasperated Stalin ordered the keeping of a “secret daybook” on his conduct, higher officials protected him.42 There is also a much darker rumor attached to his name. Vasili may have “provoked the arrest of the parents of a boy who bested him in an athletic competition.”43

In 1938, the seventeen-year-old was sent to the Kachinsk Military Aviation School, where Stalin thought he might find the discipline he needed, but again he demanded and received special privileges. Vasili was learning the power of his father’s name, which would eventually prove his undoing.

Meanwhile, Svetlana dutifully brought home her daybook with a record of her academic work and conduct. Over dinner at the Yellow Palace, her father would examine and sign it, as vigilant parents were required to do. He was proud of her. She was a good little girl. Her indoctrination was clear in the words she recorded as a third grader in a testament celebrating the achievements of Nina Groza, the school administrator: “‘Under your leadership our school has advanced into the ranks of the best schools of the Soviet Union.’ Svetlana Stalina.”44 Svetlana had become one of the little “warriors for communism.”

Until she was sixteen, like many of her fellow students, Svetlana remained an idealistic Communist, unreflectingly accepting Party ideology. In retrospect she would be appalled by how this ideology demanded the censorship of all private thought and led to the mass hypnosis of millions. She called this “the mentality of slaves.” Vasili learned cynically to manipulate the system, which, by its very nature, invited corruption. He understood early that the best way to get ahead was to betray somebody else.