Читать книгу Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva - Rosemary Sullivan - Страница 20

Chapter 9 Everything Silent, as Before a Storm

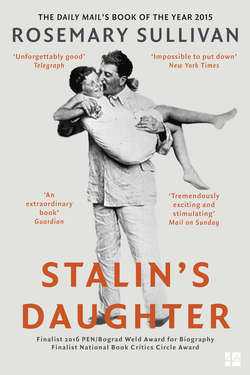

ОглавлениеSvetlana with her first two children, Joseph and Katya, in 1953.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

By 1949, Svetlana was living in the otherwise empty Kremlin apartment again. As he had done for years, her father lived at his Kuntsevo dacha. Ivan Borodachev, a commandant of State Security, ran the Kremlin household with rigor. He kept a list of any books Svetlana took from her father’s library to the dining room table to read and crossed them off when she returned them to the shelves. After the war, Stalin had initiated a regimen of having all of his food tested. Special doctors chemically analyzed every scrap of food that came from the kitchen. All foodstuffs came with official seals: NO POISONOUS ELEMENTS FOUND. From time to time, “Dr. Dyakov would appear in our Kremlin apartment with his test tubes and take samples of the air in our rooms.” Svetlana commented drily, “Inasmuch as . . . the servants who cleaned the rooms remained alive, everything must have been in order.”1

Svetlana was now a divorced woman with a four-year-old son. Her nanny, Alexandra Andreevna, was taking care of Joseph at the Zubalovo dacha. That spring Stalin visited the dacha to meet his grandson for the first time. Svetlana was terrified at the prospect of her father’s visit. Because he had refused to meet Grigori Morozov, she was worried he would reject their child as well. “I’ll never forget how scared I was,” she said in retrospect. Joseph “was very appealing, a little Greek- or Georgian-looking, with huge, shiny Jewish eyes and long lashes. I was sure my father wouldn’t approve. I didn’t see how he possibly could.”2

Yet Stalin responded warmly to the child, playing with him for half an hour in the woods. Her father even praised young Joseph: “He’s a good-looking boy—he’s got nice eyes”—affectionate words from a truculent man who offered little praise. Stalin would see his grandson only twice more. Ironically, Joseph would remember his grandfather with love; he always kept a photograph of Stalin on his desk.

Svetlana graduated from Moscow University in June 1949 with a major in modern history. She immediately entered the masters program in Russian literature. This time her father was indifferent to her passion for “those Bohemians!”

If Svetlana’s version of herself was that she was passive and vulnerable, this was not always how others saw her. Her cousin Vladimir called her character “harsh and unbalanced,” though she was “courageous and independent, with her own principles, in line with the traditions of Alliluyevs,” as he put it.3 Her friend Stepan Mikoyan felt her shyness was half camouflage. “Svetlana was very shy and quiet when everything was quiet; and when she was against something, she was very strong.”4

Candide Charkviani, by now first secretary of the Communist Party of Georgia, who had first encountered Svetlana as a child, remembered meeting her again on Lake Ritsa, where Stalin was vacationing. Svetlana had come to visit. They had been cooped up in the dacha for days until the rain finally lifted, and they set out for a walk, led by Major General Alexander Poskrebyshev, Stalin’s trusted private secretary.

Suddenly Svetlana veered off the paved road and headed toward the raging river. A large log formed a bridge to the other side and Svetlana was determined to cross. She told the others, “Don’t worry . . . nothing is going to happen to me.” “We found ourselves in an awkward position, a woman perched on stilt-like heels was clearly challenging us to cross the wildly gushing river.” Poskrebyshev stood his ground, but Charkviani followed, then was disgusted to discover that all Svetlana wanted was to pick a cluster of frozen flowers on the other bank. She skipped back across the log in her spike heels, while he crawled along the log, terrified of the river raging below. It clearly amused Svetlana to challenge her father’s comrades.5

Charkviani’s version of Svetlana was that she was stubborn and could stand up to her father. A few evenings later at the dacha, in the presence of guests who included Molotov and Mikoyan, Svetlana told her father she wanted to leave for Moscow. Stalin didn’t want to let her go. Charkviani recalled the conversation. Apparently Stalin replied,

“Why rush? Stay for some ten more days. You are not in a stranger’s house, are you? Could it be so very boring here?”

“Father, I have urgent business to look to, please let me go.”

“Let’s stop discussing this, you will stay here, with me.”

We all thought that was the final decision. Yet for Svetlana, Stalin’s words were not final. . . . Throughout the whole evening, as the ongoing conversation permitted, she would start repeating her request.

Finally Stalin lost patience:

“All right, if that’s what you want—go. I cannot make you stay by force,” he said to his capricious daughter and she happily went to her room, probably to pack her bags.

When we left the dining room, Mikoyan noted: “She has taken after her father; whatever she puts into her heart, she definitely has to do it.”6

But her rebellions were minor. In the fall of 1949, according to Svetlana, her father arranged for her to marry Yuri Zhdanov, son of the late Supreme Soviet chairman and his former second in command, Andrei Zhdanov, who had died the previous summer. She recalled: “My father . . . always hoped the two families might one day be linked in marriage,” as though it were a marriage of dynasties.7 Stepan Mikoyan concurred that the marriage was Stalin’s idea. He knew—he had been one of the candidates under consideration until he himself married.8

According to Molotov, among his ministers “Stalin loved [Andrei] Zhdanov best. He valued him above everyone else.”9 Zhdanov was humorous, lighthearted, and not a threat. Stalin had made him head of Ideology in charge of carrying out the Anti-Cosmopolitan Campaign of repression against artists and intellectuals, which he did so ruthlessly that it acquired his name—Zhdanovshchina, the period of Zhdanov.

Stalin was equally attached to Zhdanov’s son Yuri, who, from early adolescence, often stayed at Stalin’s dacha in Sochi. Yuri was only twenty-eight and had barely completed his degree in chemistry when Stalin appointed him head of the Science Department of the Central Committee. Yuri would later tell Svetlana he hadn’t wanted the job. “Oh, you know those places. The entrance is free but you pay at the exit,” he’d said.10 But one did not refuse Stalin.

Even so, it was remarkable that Yuri stepped so blithely into this marriage; he had already tasted Stalin’s wrath. The previous year, he’d become embroiled in what came to be called the Lysenko Affair.

T. D. Lysenko was a quack agronomist who ruled the world of Soviet botany. Rejecting modern discoveries about genetics, he claimed to have produced new vegetables through a process of hybridization: his most famous was a tomato-potato. He also claimed to be working on a new disease-resistant strain of wheat to solve the wheat shortages that had ravaged the country since the war. It was absurd science, but Stalin loved it, so no one dared challenge Lysenko.11

On April 10, 1948, Yuri gave a lecture that was “mildly critical” of Lysenko’s theories, though he did not mention Lysenko by name. Yuri; his father, Andrei; and two others, who had approved the lecture, were summoned to a meeting of the Politburo in Stalin’s Kremlin office the next day. Stalin was furious. “This is unheard of. They presented a report by the young Zhdanov without the knowledge of the Central Committee.” Stalin is reported to have said, “We must punish the guilty in exemplary fashion. It is necessary to question the father and not the children.”12 Two months later, Andrei Zhdanov, a heavy drinker, suffered a heart attack and was sent to a sanatorium in Valdai to recover. He died at the end of August of a massive coronary thrombosis.

Yuri Zhdanov soon published a letter of apology in Pravda, addressed to Comrade I. V. Stalin, admitting his “mistakes,” which were caused by “inexperience and immaturity.”13 His apology was disingenuous, of course, but the terrified young man put his life ahead of his science. To Svetlana, he said privately, “Now genetics are finished!”14

Clearly Stalin had forgiven him. According to Sergo Beria, who loved to gossip, Stalin played matchmaker. “I like [Yuri],” Stalin told Svetlana. “He has a future and he loves you. Marry him.”15 Svetlana claimed she was tired of resisting her father—he was old now—and she simply gave in. Stalin even added a second floor to his Kuntsevo dacha, apparently expecting the young couple to live with him. When both resisted the idea, he converted the extension into a cinema room. Stalin did not attend their elaborate wedding, but the government arranged their honeymoon on the Black Sea. It went badly. She loved the sea; he got seasick. He loved the mountains; she suffered from altitude sickness.

Relatives and friends felt Yuri made a pleasant impression. Stepan Mikoyan remembered him as “calm and intelligent, but fun at the same time.” He was a good amateur pianist.16 Yuri immediately adopted Svetlana’s son, Joseph, and mother and son took up residence in the Zhdanov family’s spacious apartment in the Kremlin.

A witness to Svetlana’s life at the time was the actress Kyra Nikolaevna Golovko.17 Kyra had first seen Svetlana as a teenager sitting with her father in his official box at the Moscow Art Theater (MKhAT) around 1943. Kyra had just returned to Moscow from evacuation in Saratov and was starring in Alexander Ostrovsky’s Hot Heart. The actors had been warned that “He” was in the audience. When Kyra caught a glimpse of Stalin’s black mustache out of the corner of her eye, her knees almost gave way. To her relief, Stalin loved the play, and “watched it, as he did The Days of the Turbins—ten or fifteen times and maybe even more.”18

Kyra met Svetlana and Zhdanov in the summer of 1949 when she and her husband Arsenii, who was chief of staff of the navy of the USSR, were vacationing at the same health spa. The couple soon moved into the House on the Embankment. They hadn’t wanted to move to “the Detention Center” from their comfortable three-bedroom apartment, but the suggestion had come from Stalin. As Kyra put it, “[Stalin] asked himself in passing whether or not we wanted to move. He rarely simply asked straight out about these types of things.”19 But it could be fatal not to pick up on his innuendo. The couple were given the five-room apartment of a navy admiral who had been arrested for passing military secrets to the British and Americans.

Kyra was worried about being so visible. Artistic friends were being repressed. Her husband’s former lover, a ballerina at the Bolshoi, had been arrested for having links with foreign intelligence, and Arsenii was fearful that the woman might denounce him. Pervaded by jealousy and betrayal, the theater world was full of “whisperers” as they were called—the informants. If Kyra was selective about whom at the MKhAT she introduced to her spouse, Arsenii was equally selective about his military associates.

At the House on the Embankment, the couple held small parties for family and close friends. The first night that Yuri and Svetlana showed up, Yuri immediately went to the piano and played, inviting Kyra to join him in a duet. The house parties were lively, with singing, dancing, listening to records, and arguing. But Kyra noticed that Svetlana sat in the corner, “somehow pulling away from the whole company,” talking quietly and never dancing. She dressed somewhat strictly in well-tailored dresses of expensive materials, often adorned with a small diamond or garnet brooch. Kyra noted that she was slender, with a beautiful athletic figure. She wore low heels and stooped slightly, probably because her husband was shorter. As they became friends, Kyra and Svetlana laughed quietly about those evenings at the MKhAT with Stalin in attendance.

One day Svetlana asked Kyra how she had trained her voice. Kyra replied that she had a wonderful teacher, a former aristocrat named Sofia Raczynskaya. Svetlana was excited. She complained that she had, by nature, a very quiet speaking voice, and now, as a graduate student, she had to give lectures at the university. Besides, Yuri had a wonderful voice. “He’s very sociable and loves to sing, while I, as you can see . . . Yuri’s at the piano, and I sit alone.” Kyra promised to ask her teacher to give Svetlana voice lessons.

When Kyra approached her the next day, Raczynskaya almost had a heart attack. She slumped and her hands shook as she said, “Kyra! What are you doing to me?” Kyra helped her to sit. She explained how nice Svetlana was. After much coaxing, Raczynskaya agreed. “Well, Kyra, for your sake.”

A few days later, Raczynskaya sat waiting for her new pupil to arrive. She lived in a communal apartment on Vorovskogo Street in one very large room filled with antique cabinets, a piano, stacks of books, and boxes of memorabilia. Two hours before the lesson, there was a knock on the door. Three men in civilian dress entered. They searched her room, turning everything upside down. Nothing was said. Before the men left, everything was put back exactly in its right place.

Svetlana, unaware of what had just happened, arrived twenty minutes later carrying flowers, a box of candy, and two bags of food. Raczynskaya had refused to accept payment for the lessons, but even so, she felt a little embarrassed at this largesse. Raczynskaya soon learned not to speak to friends about Svetlana. When she told one acquaintance about her new pupil, he disappeared from her life for years.

Svetlana didn’t have much of a voice, but Raczynskaya believed all people had the potential to be vocalists; one just had to open them up. The lessons continued. Each time, three plainclothes policemen arrived two hours before Svetlana to “shake up” the room. Each time it was a different three men, but each time they acted identically. Unnerved by this mechanical mimicry, Raczynskaya took to phoning Kyra to report on the trinity of suits. Feeling guilty, Kyra said she would ask Svetlana to stop her lessons. Raczynskaya replied, “No, no! If Svetlana needs this, we will continue.” As Kyra put it, “Sofia Andreyevna, in spite of her age, was a gambling woman.”

This was the way much of the Soviet intelligentsia, especially in Moscow, lived. Spies, informants, secret police were legion. It was never possible to understand what was going on behind the scenes; one only felt the impact. It was like living on a bed of quicksand and pretending that the ground was solid.

It was willful blindness that Svetlana, who placed the highest value on art and literature, should have followed her father’s directive and ended up in the Zhdanov household. As the enforcer of Zhdanovshchina, Yuri’s father had been the official most hated by artists and intellectuals. He’d suppressed the music of Prokofiev, Khachaturian, and Shostakovich as “alien to the Soviet people and its artistic taste” and had banned the work of many writers, including the poet Anna Akhmatova. Of Akhmatova he infamously said, “She is a half-nun, half-harlot or rather harlot-nun whose sin is mixed with prayer.”20

The Tretyakov Gallery, where Svetlana had once gone with her beloved Aleksei Kapler, mounted a show that winter of 1949 in honor of Stalin’s seventieth birthday (actually his seventy-first). Every canvas was a grotesque portrait of Stalin: the kindly grandfather, the war hero, the legendary knight. When she saw the exhibition, Svetlana was devastated. Art was being prostituted to gratify her father. But here she was in the Zhdanov family where Zhdanovshchina had originated. What did she expect?21

The whole marital exercise proved a disaster, another mistake. Even after Zhdanov’s death the previous year, the Zhdanov family kept up the rhetoric of partiinost (party-mindedness). The apartment was filled with war booty—vases, rugs, works of art—carted back from Germany after the war. “The most orthodox Party spirit reigned in the house I lived in, but . . . it was all hypocritical, a caricature purely for show.”22 Svetlana found that she detested her mother-in-law, who, she felt, had her son tied to her apron strings. Yuri called her “the wise old owl.”

Svetlana was soon pregnant again. Through the entire first winter of her marriage, she was very ill. She entered the hospital that spring of 1950 and remained there one and a half months. It turned out that Svetlana and her husband had incompatible blood types, which caused her to develop toxicosis affecting her kidneys. She almost died. Her baby daughter was delivered in May, two months premature, and after the delivery Svetlana spent another month in the hospital.23

Feeling alone and unloved, she turned to her father to pour out her woes, telling him about his new granddaughter, Yekaterina (Katya). He replied:

Dear SVETOCHKA!

I got your letter. I’m very glad you got off so lightly. Kidney trouble is a serious business. To say nothing of having a child. Where did you ever get the idea that I had abandoned you?! It’s the sort of thing people dream up. I advise you not to believe your dreams. Take care of yourself. Take care of your daughter, too. The state needs people, even those who are born prematurely. Be patient a little longer—we’ll see each other soon. I kiss my Svetochka.

YOUR LITTLE PAPA24

Though her father did not visit her in the hospital, she was pleased to get his letter. But there was always the barb—the state needed her premature baby, who was just then fighting for her life.

The marriage lasted another year, but it was obvious to both Svetlana and Yuri that it was doomed. Yuri’s mother and Svetlana could not stand each other. At the Science Section of the Central Committee, Yuri continued to feel the noose tightening. Instead of drawing together, both withdrew into their own woes. Svetlana complained:

He wasn’t home much. He came home late at night, it being the custom in those years to work till eleven at night. He had worries of his own and with his inborn lack of emotion wasn’t in the habit of paying much attention to my woes or state of mind. When he was at home, moreover, he was completely under his mother’s thumb. . . . [He] let himself be guided by her ways, her tastes and her opinions. I with my more easy-going upbringing soon found it impossible to breathe.25

It’s hard to think of Svetlana’s upbringing as easygoing. What she probably meant was that the home was full of emotional noise: Grandma Olga, Anna, and Zhenya all spoke their minds. And she, behind the docile public façade, was “vehement about everything.”26

But it was more complicated than facades. It was not possible for either her or her husband to go into the interior dark spaces where the fear and anger raged. It was not possible to engage real emotions in these families where nothing was said. Did she and Yuri discuss his father, her father, what was happening in the world beyond their walls? That seems impossible. Was what she called an “inborn lack of emotion” simply an inability to speak truthfully? And yet it was also true that in orthodox Bolshevik circles, certain kinds of emotion were seen as weakness or self-indulgence.27

Her old acquaintance, the actress Kyra Golovko, was passing the Kremlin one day. To avoid the crowded trolleys, she often walked to the Moscow Art Theater over the Stone Bridge, past the Kremlin. Once, as she passed the Borovitskie Gates, she heard a voice calling her name. She shuddered in fear, but then looked up to see Svetlana approaching her. They had lost touch, each consumed by her own worries.

Svetlana begged Kyra to walk with her. She needed to talk. Kyra remembered how upset she seemed, and recalled the conversation, particularly because this was the only heart-to-heart they managed to have. Svetlana had always been so private and restrained, and few dared to speak openly with her.

Svetlana told Kyra that she wanted to divorce Yuri. Kyra was shocked. To her, Yuri and Svetlana had seemed so much in love: those voice lessons, wearing low heels, “all was done for Yuri’s sake.” And there was her new daughter, Katya.

Kyra recalled Svetlana’s words:

“It’s Yuri’s mother. From the outset she was against my marrying him. And now we are all on the brink of disaster. It came to the point that I even rushed to my father.”

“And what did he say?” I asked.

“He said that marriage is an endless chain of mutual compromises and that if you give birth to a child, you must somehow save the family.”

“You told Yuri about this conversation?”

“Yes, but it had almost no effect. His mother thinks I ruined his talent as a scientist and as a pianist.”

By this time, the two women had reached the Moscow Theater, where they parted. Kyra remarked, “Thus ended my relatively close relationship with Svetlana.”28

Svetlana and Yuri separated. Knowing that they would not be allowed to divorce without Stalin’s permission, she wrote warily to her father, signing her letter “your anxious daughter”:

FEBRUARY 10 [NO YEAR]

Dear Papochka,

I would like to see you very much to let you know about how I live. I would like to tell you all of this in person—tête-à-tête. I tried several times and I didn’t want to bother you when you weren’t very well and you were very busy. . . .

In connection with Yuri Andreevich Zhdanov, we decided to finally separate even before the New Year’s . . . for two years, [we] have not been husband or wife to each other but have been something indescribable.

Especially after the fact that he proved to me—not with words but with actions—that I’m not dear to him, not one bit, and I’m not needed. And after that he repeated, for the second time, that I should leave my daughter with him. Absolutely not . . .

I’m done with this dry professor, heartless erudite, he can bury himself under all his books but family and wife are not needed by him at all. They are well replaced by his numerous relatives. . . .

So, Papochka, I hope that I will see you, and, you, please do not be angry with me that I informed you about these events post-factum. You were aware of this even before.

I kiss you deeply.29

In the summer of 1952, Svetlana got her father’s permission to divorce Yuri.

Again it is Candide Charkviani who reports the story of how Svetlana approached Stalin to tell him of her final intentions:

My third meeting with Svetlana was so peculiar that I remember it rather well. Before it was 1 PM, I had already arrived at Stalin’s Kuntsevo residence. After a brief discussion, J. Stalin excused himself. “Don’t get bored,” he said and left the room. Some while later he returned freshly shaved in a well-ironed service jacket and trousers. Before we started discussing the issues I came with, there was a knock on the door. The guest turned out to be Svetlana. Stalin greeted her with enthusiasm, kissed her and, while pointing to his jacket, said: “Look how I got dressed up for you, I even had a shave.” Svetlana shook my hand and we all sat round the table.

As some banalities were exchanged, a silence fell. Stalin expected Svetlana to start; however she kept silent.

“I know what you are going to say,” said Stalin finally, “so you still insist on your decision to divorce?”

“Father!” pleaded Svetlana.

As I felt the conversation was to touch on family matters, I got up and asked J. Stalin for permission to go for a walk in the garden.

“No!” cut in Stalin categorically, “you need to be here. It is necessary.” Then he turned to Svetlana and promised to be the first one to spread her news to the world.

I had no other way but to be an unwilling witness to an unpleasant discussion of private matters. I took my seat rather far away; however the host was conversing in such a loud voice that it was impossible to escape hearing it all.

“What’s besetting you? What’s your reason for wanting a divorce?”

“I cannot stand my mother-in-law. I have not managed to adjust to her ways,” mumbled Svetlana.

“And your husband? What is your husband saying?”

“He is supporting his mother in everything.” . . .

“All right, if that’s what you have decided, get a divorce. Such matters cannot be settled by force. Yet I want you to know that I don’t like your attitude to family life.”

That was J. Stalin’s final verdict in this awkward affair. Svetlana, probably satisfied but blushing because of embarrassment, said goodbye and left us.30

In retrospect, Svetlana would say that Zhdanov was very intelligent, cultured, talented in his field, and a wonderful father but that they lived in different universes. He, too, wanted a divorce. He remained friendly toward her and devoted to his daughter, Katya, and would take both of her children on his hiking and archaeology expeditions.31

Stalin gave his twice-divorced daughter permission to leave the Kremlin, assigning her an apartment in the House on the Embankment. Her old nanny, Alexandra Andreevna, came with her, perhaps more of a responsibility now than a help. The apartment, number 179 on the third floor, entrance seven,32 was modest—four rooms with a kitchen—but certainly extreme luxury in comparison with the communal apartments into which most Muscovites were crammed, where several families might share a single room separated by sheets of plywood and where there were always fights over the communal kitchen and toilet and constant reports to the Housing Committee about noisy children being brought up like hooligans.

Svetlana was now twenty-six and in the last year of her MA studies. Her father asked her how she would survive. Having left Zhdanov, she was not entitled to a government dacha or an officially chauffeured car. A new law in 1947 had decreed that relatives of members of the government would no longer be fed and clothed at public expense. She recalled he almost spat at her: “What are you, anyway—a parasite, living off what you’re given? . . . Apartments, dachas, cars—don’t think they’re yours. It doesn’t any of it belong to you.”33

She explained that she didn’t need a dacha or a chauffeur. Her stipend as a graduate student was enough to pay for her and the children’s meals and the apartment. He calmed down. Thinking it a magnificent sum, he passed her several thousand rubles. He didn’t know that the currency had been so devalued that the amount would barely cover living expenses for a few days. Svetlana said nothing.34

However, Stalin offered to buy her a car, but only if she got her driver’s license first. This would become one of her fondest memories. She would always recall the one and only time she took her father out for a drive. His bodyguard sat in the backseat, rifle across his knees. Stalin seemed so pleased to discover that his daughter could drive.35

But, in truth, Stalin and his daughter were growing more distant. On October 28, she wrote to him:

OCTOBER 28, 1952

My Dear Papa,

I very much want to see you. I don’t have any “business,” or “questions” to discuss. I just want to see you. If you would allow me and if this wouldn’t bother you, I should like to ask if I could spend some time at the Blizhniaia [Kuntsevo] dacha—two days of the holidays—the 8th and 9th of November. If it’s possible I will bring my little children, my son and daughter. For us this will be a real holiday.36

Svetlana took the children to visit Stalin’s dacha on November 8. It was the first time he saw the two-and-a-half-year-old Katya and the only time he, Svetlana, and his two grandchildren were together. It was also the twentieth anniversary of Nadya’s death, though this was not mentioned. Svetlana wondered if her father remembered that this was the date on which her mother had committed suicide.

Svetlana looked at her father’s dacha with loathing. His rooms were ugly. In cheap frames on his walls he had huge photographs cut out from the magazine Ogonyok: a little girl with a calf, some children sitting on a bridge. Strangers’ children. Not a single photograph of his own grandchildren. The unchanging rooms—a couch, a table, chairs; a couch, a table, chairs—frightened her. The little party went off well, but Svetlana felt her father’s response to her daughter was indifference. He took one look at Katya and burst out laughing. Svetlana wondered if her father would have liked to be a family again. When she had fantasies of herself and her children living under the same roof with him, she realized that he was accustomed to the freedom of his solitude, which he claimed to have come to appreciate during his long Siberian exiles. “We could never have created a single household, the semblance of a family, a shared existence, even if we both wanted to. He really didn’t want to, I guess.”37

She went alone and without a present to celebrate his seventy-third (seventy-fourth) birthday on December 21. Beria, Malenkov, Bulganin, and Mikoyan were at the birthday party. Khrushchev came in and out. Molotov was unwelcome; Stalin had singled him out for savage humiliation at the Nineteenth Congress that October, and his wife, Polina, had been exiled to Kazakhstan for speaking in Yiddish at an official cocktail reception and declaring recklessly that she was a “daughter of the Jewish people.”38

Stalin was ebullient. The kitchen staff had laid out a Georgian feast. Even with the “poison tests” conducted in the kitchen, Stalin still made sure someone tasted any dish before he ate it. Khrushchev remembered the drill: “Stalin would say, ‘Look, here are the giblets, Nikita. Have you tried them yet?’” Khrushchev would reply, “‘Oh, I forgot.’ I could see he would like to take some himself, but was afraid. I would try them and only then would he start to eat them himself.”39

When Stalin put Russian and Georgian folk songs on the gramophone, everyone had to dance. As Khrushchev described him, “He shuffled around with his arms outstretched. It was evident he had never danced before.” Then Svetlana appeared. Khrushchev recalled:

I don’t know if she’d been summoned or if she came on her own. She found herself in the middle of a flock of people older than she, to put it mildly. As soon as this sober young woman arrived, Stalin made her dance. I could see she was tired. She hardly moved while dancing. She danced for a short time and tried to stop, but her father still insisted. She went over and stood next to the record player, leaning her shoulder against the wall. Stalin came over to her, and I joined them. We stood together. Stalin was lurching about. He said, “Well, go on, Svetlanka [sic], dance! You’re the hostess, so dance!

She said, “I’ve already danced Papa, I’m tired.” With that, Stalin grabbed her by the forelock of her hair with his fist and pulled. I could see her face turning red and tears welling up in her eyes. . . . He pulled harder and dragged her back onto the dance floor.40

Svetlana denied that her father had ever pulled her onto the dance floor by the hair, but this birthday party would turn out to be her last encounter with him. Stalin was certainly drunk. Perhaps he was gloating. He was in the midst of engineering his last and most terrifying ideological campaign, the “Doctors’ Plot.”

On January 13, 1953, the TASS news agency published a government statement officially announcing the plot.

From the latest news.

Arrest of a group of subversive doctors.

Some time ago, the bodies of State Security uncovered a group of terrorist doctors who set themselves the task of cutting short the lives of prominent public figures in the Soviet Union by administering harmful treatments.41

The editorial in Pravda that day was titled “Evil Spies and Murderers Masked as Medical Professors.” The “killer doctors” were called “murderers in white coats.” Nine doctors, six of them Jewish, were identified by name.

Dr. Yakov Rapoport, a distinguished Soviet pathologist, was arrested on February 3. In a memoir, he described the atmosphere of the time:

We were aware of a marked thickening of the political and social atmosphere, a thickening oppression that was near the point of suffocation. The feeling of alarm, the premonition of dire and inevitable disaster, achieved a nightmare intensity at times, supported, moreover, by actual facts.42

The public, whipped into a frenzy by news reports, cursed the bloody killers and thirsted for revenge. People refused to be treated by Jewish doctors.

Dr. Rapoport was arrested as a murderer and a member of an anti-Soviet terrorist organization. Like all the doctors, he was submitted to a “secret lifting,” the MGB* term for a sudden disappearance. The MGB men came for the targets in the middle of the night, searched all their belongings, and confiscated savings passbooks, bonds, and any money. This was a strategy to impoverish the families in order to see which fellow conspirators would come to their aid. Encountering the wife or children of an arrested person on the street, people averted their eyes. The prisoners were carted off to Lubyanka or Lefortovo prisons. Having no clue as to what was going on, the remaining family members waited in terror for the secret police to return.

Dr. Rapoport remembered that “initially the Doctors’ Plot had no nationalistic coloring; both Russian and Jewish doctors were implicated. But before long it was given an anti-Semitic slant.”43 Jews could be found in all strata of Soviet society, and Russia’s long history of anti-Semitism could be counted on to induce people to believe any slanders against them. All Stalin needed was the doctors’ confessions. The well-tried strategy was simple: “If they confess, it must be true.”

It is also virtually certain that a “Writers’ Plot” would have come next. A report from a source at the Writers Union, sent to the Central Committee’s Department of Propaganda, claimed that the Literary Gazette “pandered to Jews and was dominated by Jews.” Its editor, the well-known writer and war hero Konstantin Simonov, was purportedly Simonovich, born to a Jewish family and the son of a publican on the estate of Countess Obolenskaya. In fact, Simonov was not Jewish. He was the son of Princess, not Countess, Obolenskaya and his father was Mikhail Simonov, a colonel in the tsar’s army. Simonov laughed when he heard this slander, but he would soon grow very concerned to discover that he was identified as head of a group of people in Moscow’s literary world connected to the cosmopolitan conspiracy. His editor warned him: “There are some bastards out to get you who want to dig your grave, come what may. And just remember, absurd though it is, it was all said with such seriousness that I couldn’t believe my ears.”44 This was how one became a target.

Svetlana recalled the atmosphere of that last year. “During the winter of 1952–1953 the darkness thickened beyond all endurance.”45 It was “terribly trying for me, as for everyone. The whole country was gasping for air. Things were unbearable for everyone.”46 So many relatives, friends, and acquaintances were in jail or camps: her aunts and cousin for “babbling” too much, Polina Molotov for Zionist plotting, and Lena Stern as a member of the Jewish anti-Fascist Committee. She had consulted Stern for advice on the treatment of tubercular meningitis for the child of a close friend.47

Svetlana listened as Valechka, her father’s faithful housekeeper, told her that Stalin was “exceedingly distressed at the turn events took.” Valechka had heard him say that “he didn’t believe the doctors were ‘dishonest’ and that the only evidence against them was the ‘reports.’”48 But even Svetlana must have known by now that this was pro forma for her father. Stalin, the consummate actor, pretended to sit back as others brought reports to him of enemies, whom he could not refuse to punish, while of course he was the puppet master manipulating the strings behind the scenery.

At the time, Svetlana heard rumors that a third world war with the West was imminent. A friend of her brother, an artillery colonel, told her, “Now it’s the time to begin, to fight and to conquer, while your father is still alive. At present we can win.”49 Was this war plot truly afoot? Vasili’s friends were hotheads and unreliable, but George Kennan, the American ambassador to the USSR, was expelled after only four months. Still, it is unlikely that Stalin was planning outright war. Some historians believe he was in the process of organizing a major deportation of Jews, though this is based only on hearsay. Whatever was going on, the doctors’ fates hung in the balance. And the pressure was unbearable. Everyone was afraid to speak. Everyone was silent, “very still as before a storm.”50

And then Stalin died.