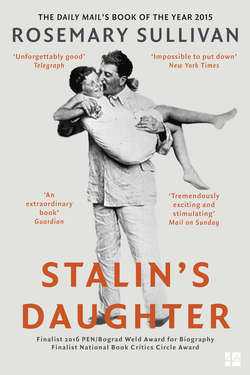

Читать книгу Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva - Rosemary Sullivan - Страница 17

Chapter 6 Love Story

ОглавлениеSvetlana, age sixteen.

(Meryle Secrest Collection, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University. Courtesy of Chrese Evans)

By January 1942, the Red Army had driven the Wehrmacht from Moscow’s gates. The skeletal remains of German tanks lay like burned husks outside the city. Hitler had drastically miscalculated both Russian wiliness in tactical defense and the brutality of the Russian winter. It is estimated that one million Russians, both military and civilian, died, but Stalin won the battle for Moscow. In June Svetlana and her retinue were given permission to return to Moscow. The previous autumn, a fire had almost destroyed the Zubalovo dacha; the family moved into the surviving wing. By October an ugly new house, painted camouflage green, was built in the shell.

Svetlana did not see her father until August, when she was summoned to his Kuntsevo dacha to attend a dinner for Churchill. The British prime minister had flown to Moscow for a consultation about Allied strategy. The news Churchill was bringing was not good. There would be no Allied second front to distract Hitler from his assault on the USSR for a good while yet.

Svetlana had no idea why she was summoned to this dinner. Her father forbade any interaction with foreigners, and she was never included in diplomatic circles. When he introduced her to Churchill and said she was a redhead, Churchill remarked that he too had been a redhead but, waving his cigar over his bald pate, said, “Look at me now.” She was too shy to respond. Very soon, her father kissed her and told her to run along. Reflecting on this strange moment much later, she concluded that her father had been performing for Churchill, demonstrating what a charming domestic life he had.1

Svetlana was still a schoolgirl in the tenth grade. She was reading Schiller, Goethe, Gorky, Chekhov, and the poets Mayakovsky and Yesenin. She loved Dostoyevsky, even though her father had banned his books. Slowly she was growing into an independent-minded young woman. But according to her friend Marfa Peshkova, Stalin was becoming more and more disapproving of his teenage daughter. If she wore a skirt above her knees, wore shorts, or wore socks instead of stockings, he would rage: “What’s this! Are you going around naked?” He ordered her to wear sharovary (baggy pants tight at the ankles) and had a dress made for her that covered her legs.2 His reprimands often brought Svetlana to tears, but she was stubborn and staged her rebellion shrewdly. She heightened the hem of her dress slowly until it was back above her knees. She knew her father was too busy to notice.

In the autumn of 1942, a new student, Olga Rifkina, entered Model School No. 25. Olga had an unusual background for this elite school. She was from a poor Jewish family living in a one-bedroom communal apartment shared with two other families. Her mother kept them all going by working as a journalist for Pravda. The year 1941 had been terrible. That June the government had issued a directive for the evacuation from Moscow of all children under the age of three. Olga and her mother, grandmother, and baby brother Grisha left for Penz. When they returned to Moscow in May 1942, Olga had missed a year of school.3 Model School No. 25 had special placement for such children. She was enrolled and sent to live with her grandmother.

Olga’s memories of the school were mostly unhappy. While the teachers never singled out students who were poor, the other children made her aware of her inferiority. She would look back and say, “Only one person, who seemingly had the most reason to preen, . . . was a true ‘personality’ not tied to her position. This was Svetlana Stalina.”4 Olga remarked in an interview:

I really did like Svetlana very much right away. . . . She was a particularly humble person. And even shy. And she had a lot of charm and femininity. She attracted my attention. I always looked admiringly at her. And our friendship survived all our lives. Until the last day.5

Soon the two girls became deskmates. After school they would take long walks along the Moskva River, though these walks were often interrupted when Svetlana would suddenly say, “I can’t be late. My Papa is coming. I haven’t seen him in two weeks.” Olga had the impression that, like most people, Svetlana thought of her father as the “great, big Stalin, but not exactly a father.”6

Because of the food shortages caused by the war, most people, including Olga’s family, often went hungry. Olga recalled that, after coming home from school, she would eat a bowl of soup and then, with a glass of kakavella (a drink made from boiled cocoa pods), do her homework. When there was no food for the evening, her grandmother would tell her to go to bed while she still wasn’t hungry; otherwise she’d never be able to sleep. Olga remarked, “Svetlana, of course, could not imagine any of this. At the time she was artificially isolated from regular life. . . . She never had to buy anything, she could barely tell the denominations of money apart.”7

At school, Svetlana did not parade as Stalin’s daughter. She often complained that the other students looked on her as if she were an “insider” and had access to secret information. But she assured Olga, “I don’t know anything, nor do I really care.” She hated the teacher who made her write out lists of all the things that carried her father’s name: the mountain in Perm, Stalingrad on the Volga, the ZiS car (Zavod imeni Stalina, Factory in the Name of Stalin). Olga recalled: “Poor Svetlana. She wanted so much to be equal with everyone else. I remember once she stepped on a young man’s foot and he called her a ‘ginger cow’—she even beamed with joy.”8

One indication of her status, however, was that Svetlana had her bodyguard, Mikhail Klimov, who had accompanied her in the evacuation to Kuibyshev. Most of the elite children had bodyguards—the Molotov children had three. The bodyguards had their own separate room beside the school cloakroom, where they spent their day. Both Olga and Svetlana played piano, and they often went to the conservatory together to hear music by their favorite composers: Bach, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, or Prokofiev. Klimov would buy the tickets. If there was violin music on the program, he would complain: “We are going to saw the wood again” and sit behind them, shuddering.9 Svetlana claimed to have grown fond of Klimov, but it was disconcerting to have someone always shadowing her.

Both girls were readers. Svetlana had a copy of the 1925 Anthology of Russian Poetry of the Twentieth Century. Together they would read the subversive work of Anna Akhmatova, Nikolai Gumilyov, and Sergei Yesenin. While still in grade ten, Olga gave Svetlana a notebook full of her poems. She felt Svetlana was a kindred spirit: she, too, had had her happy childhood shattered by misery; she, too, was deeply attached to her absent mother. In response, Svetlana wrote a poem to Olga:

Through poetry, as if through clear tears, looking

Into her soul, again and again

How can I not understand her, if I too am

Waiting in vain for my dear mother? . . .

To the lovely girl with the eyes of spring

I find I am unable to speak

About myself and about how close and clear

Are her thoughts, her dreams, and her grief.10

Though addressed to Olga, the poem was really an elegy for Nadya, now dead ten years. It spoke to Svetlana’s terrible isolation. Nothing of the pain of loss had healed. Olga slowly came to realize that Svetlana was “essentially an orphan.”11

After her return to Moscow, Svetlana spent much of her time at the Zubalovo dacha while her father, preoccupied with the war, was mostly in his bunker hunkered down with his Politburo. Her brother Vasili also lived at Zubalovo with his wife, Galina. Now twenty-one, Vasili had graduated from the Lipetsk Aviation Institute. In October 1941 he became a captain. By February 1942, he had been promoted to colonel. His friend Stepan Mikoyan, wounded and in the hospital, recalled his surprise when Vasili visited him in Kuibyshev in his colonel’s uniform. According to Mikoyan, Vasili later explained that his father had taken him aside and told him he didn’t want him to fly. Too many sons of the elite had already been lost: Mikoyan’s brother, Khrushchev’s son, the war hero Timur Frunze. Vasili was appointed chief of the Air Force Inspection Command to keep him grounded. He flew only one or, at most, two combat missions. Though Stalin was often strict and rude with Vasili, Stepan Mikoyan believed he actually loved his son. Vasili soon had a grand office in Moscow on Pirogov Street.12

Stalin’s younger son, Vasili, was a colonel of the Red Army Air Force by the time this photo was taken in 1943.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Vasili surrounded himself with fellow pilots and treated them like courtiers. He liked to fete them at Aragvi, his favorite Georgian restaurant, where the food was lavish even when the war was raging and Moscow was still being bombed. An orchestra played the latest dances, and the Russian elite sang into their vodka.13

That fall Vasili turned Zubalovo into a party house; he particularly liked pilots, actors, directors, cameramen, ballet dancers, writers, and famous athletes. Stepan Mikoyan thought he gave these late-night drinking parties in subconscious imitation of his father, who used to summon select members of his Politburo to Kuntsevo and keep them up drinking until four or five a.m.14 Most who came were somehow involved in the war—the pilots were flying bombing missions; the filmmakers were shooting footage at the front, often from inside the trenches or with cameras mounted on tanks; the writers were working as journalists covering the war. The evenings had a Hemingwayesque flamboyance. Everyone came to watch films in the small private cinema at the dacha and to listen to the American jazz tunes that were constantly churning on the record player. There would be long drunken nights with people dancing the fox-trot. For many the hard edge of death framed the moment with an intensity unknown in peacetime.

Vasili insisted that his sister come to the parties. Svetlana mostly watched the bacchanal from the sidelines. Friends who attended, like Marfa Peshkova, noted that she had suddenly turned into an attractive young woman, though she still seemed closed off in her own private torment. Sometimes the parties got out of hand. On one occasion, when Vasili was very drunk, he insisted that his pregnant wife tell a joke. When she refused, he hit her, though luckily she fell back onto a couch. Enraged, Svetlana threw her brother out of the house along with his drunken buddies. Yet the parties continued.15

Svetlana with her friend Stepan Mikoyan, the son of the long-standing Soviet official Anastas Mikoyan, in 1942.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Svetlana assumed that no one noticed her, but she had caught the attention of Aleksei Yakovlevich Kapler. The Jewish Kapler, then thirty-eight, was one of the most famous screenwriters in the USSR. He was the author of the epic films Lenin in October and Lenin in 1918, and in 1941 he had been awarded the prestigious Stalin Prize. Kapler was supposedly working with Vasili on a film about air force pilots, though evenings were spent mostly drinking, and the film was never made. Kapler was within the inner sanctum of the head of state—best friends with the dictator’s son, who was wild and outrageous. It was heady stuff. He was obviously a man who loved risk. Though he was married, he and his wife were separated, much to his distress, and he was on his own.

One night the Zubalovo group was invited to a film preview on Gnezdnikovsky Street, and Svetlana found herself talking with Kapler about movies. All those years of watching films in the Kremlin with her father paid off. Kapler was intrigued. Describing his impression of her to a journalist years later, Kapler said that he had been surprised. Svetlana was not like the other girls in Vasili’s retinue. She was not what he expected. He was taken with “her grace and intelligence . . . the way in which she would talk to those around her, and the criticisms she made on various aspects of Soviet life—what I really mean is the freedom within her.”16 Her “judgments” were “bold and her manner unpretentious.” She was not decked out like the other women in their gorgeous outfits, preening for attention. She wore “practical, well-made clothes.”

An undated photograph of a young Aleksei Kapler, probably one of the two hundred photographs stolen from Svetlana’s desk by the KGB agent Victor Louis.

(Public domain)

On November 8, a party was organized at Zubalovo to celebrate the anniversary of the Revolution. The guests included the famous, like the writer Konstantin Simonov, whom Svetlana admired, and the documentary filmmaker Roman Karmen. Much to her surprise, Kapler asked her to dance. She felt awkward and clumsy. She was so young. He asked her why she seemed sad and asked about the lovely brooch she was wearing, a decorative touch to her austere outfit. Was it a gift, he wondered? Svetlana explained that it had belonged to her mother and this day was the tenth anniversary of her mother’s death, though no one else seemed to remember or care.17 As he held her, she poured out her life. She spoke of her childhood, of the losses she had endured, though she didn’t talk much about her father. Kapler understood that “something seemed to separate them.”18

Charming, daring, knowledgeable, experienced, Kapler was irresistible to an idealistic girl of sixteen. And he seemed to be equally drawn to her. The first film they saw together was Queen Christina (1933), starring Greta Garbo and John Gilbert, a biopic of the seventeenth-century queen of Sweden, which distorted and absurdly romanticized her life. It is not hard to imagine the film’s impact on the impressionable young Svetlana as war raged in Moscow.19

“Spoils, glory . . . what is behind those big words? Death and destruction. I want people to cultivate the arts of peace,” says Garbo’s Queen Christina. The film is about “great love, perfect love, the golden dream.” The queen falls in love with Antonio, envoy from the king of Spain. “I have grown up in a great man’s shadow,” Garbo cries. “I long to escape my destiny.” “There is a freedom which is mine and which the state cannot take away.” Kapler recalled how they both identified with the film. She was the rebellious “royal daughter” demanding her own life; he was poor Don Antonio, the lover aspiring above his station.

Kapler brought Svetlana books that were forbidden, including Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. He’d gotten hold of a Russian translation that was circulating privately among friends.20 The novel had been officially banned; Hemingway’s portrait of the murderous Communist commissar who directed the purges of Trotskyites in the Spanish Civil War was too revealing.

The couple looked for pretexts to be together. Of course the meetings had to be kept secret from her father. Kapler would wait for Svetlana outside her Model School, lurking, embarrassed, down the lane. They would walk in the woods, he holding her hand in his pocket, or amble along the Moscow streets under blackout, or go to the unheated Tretyakov Gallery and wander the halls for hours. They went to private film showings at the Cinema Artists’ Club and at the Ministry of Cinematography on Gnezdnikovsky Street. They saw musicals starring Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, as well as Young Mister Lincoln and Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. They met at the Bolshoi and were most happy when they got the chance to stroll through the foyer during the performance.21

Mikhail Klimov, Svetlana’s bodyguard, was always a few paces behind them. Kapler even enjoyed his company, offering him the occasional cigarette. Svetlana felt Klimov was kind and even pitied her “absurd life.”22 Perhaps they thought he wouldn’t betray them, but in fact Klimov was terrified by their growing liaison. He knew that Stalin had his daughter’s phone tapped and her correspondence opened, and that NKGB agents made daily reports to him on all her activities.

After all, what were they doing? With her guard constantly on their heels, they could never be physical lovers, and this charged their relationship with a romantic desperation. She thought Kapler the “cleverest, kindest, most intelligent person on earth.”23 For him, she was a bright Lolita, a child longing to be taught about the world. She was so appallingly lonely, “surrounded and oppressed by an atmosphere worthy of a god.” “Sveta really needed me,” Kapler said.24

The lovers blithely enjoyed their little deceptions. Kapler’s friends called him Lyusia (which sounds like a woman’s name). Svetlana would go over to her grandmother’s apartment in the Kremlin to phone Kapler. Grandma Olga always thought she was talking to a girlfriend.25

Soon Kapler left on an assignment to cover the guerrilla war in Belarus, one of the most dangerous of the partisan fronts, and then he traveled to Stalingrad to cover the Battle of Stalingrad for Pravda. In the December 14 issue of Pravda, he published an article called “Letters from Lieutenant L from Stalingrad—Letter One,” by Special Correspondent A. Kapler. The letter purported to be a soldier’s description of Stalingrad to the woman he loves:

My love, who knows whether this letter will reach you? A really difficult journey awaits it. I will nevertheless hope this letter will reach you, that it will carry, under the enemy’s fire across the Volga, across the prairies, through storms and blizzards towards our lovely Moscow, my tenderness towards you, my dear.

Today it snowed. It is winter in Stalingrad. The sky descended and became low as the ceiling in an izba. This gray, cold weather is especially agonizing on a day like this. One thinks of their loved one. How are you doing now? Do you remember Zamoskvorech’e? Our rendezvous in the Tretyakov gallery? How, while it was closing, the guard was kicking us out by ringing his bell, and how we could not recall which painting we sat in front of all day, while looking into each others’ eyes. Until now, I know nothing about that painting except that it was wonderful to sit in front of it, and I thank the artist for that.26

Kapler went on to describe the war to his lover. The article reads like a film script about the heroic purity of war, in which love, suffering, friendship, and death are focused a million times more intensely than in ordinary life. Caught up as they were in the frenzy of romantic obsession, it was as if the lovers, too, were living in a film. Kapler ended his letter on a note of longing:

It is almost evening. It is also almost evening in Moscow. You can see the ragged Kremlin wall from your window and the sky above it—Moscow’s sky. Perhaps, it is also snowing there right now.

Your,

L.

It is impossible to imagine Stalin’s outrage as he read this and recognized the reference to Svetlana. Kapler later claimed he hadn’t intended to send the article to Pravda. “Friends had played a trick on him.”27 But he had dared to write a love letter to the dictator’s daughter, an indiscretion that should have been unimaginable. Marfa Peshkova remembered Svetlana bringing the newspaper to school. Though Svetlana understood the danger of Kapler’s words, it was also clear she was deeply moved.28

When Kapler returned to Moscow for the New Year’s celebrations, Svetlana told him they must not meet or even call each other. They managed silence until the end of January and then resumed their phone calls. They developed a code. He or she would call and blow air twice, to say, without words, “I’m here. I remember you,” and hang up.29

One evening at the beginning of February, Kapler got a phone call. The gruff voice on the other end of the line was that of Colonel V. Rumyantsev, second in command of Stalin’s security detail. He told Kapler the security agents knew everything and suggested he leave Moscow immediately. Kapler replied, “Go to Hell.”30

Through February, Kapler and Svetlana resumed their walks in the woods and their theater outings, with her bodyguard in tow. At the end of February, they arranged a last rendezvous. They found an apartment near the Kursk Station used by Vasili’s pilot friends for assignations. But the faithful Mikhail Klimov stayed with them. Svetlana persuaded him to sit in an adjoining room, though he insisted on keeping the door open. In silence the lovers kissed for the last time. They were ecstatic at touching, grief-stricken at parting; their leave-taking was devastating to Svetlana. It was February 28, her birthday. She had just turned seventeen.

Kapler was preparing to leave for Tashkent to shoot a movie based on his screenplay In Defense of the Fatherland. As Kapler reported it, on March 2 he drove to a committee meeting for the film industry. As he got out of his car, a man approached, flashed an identity badge, and told him to get back in. The man got into the passenger seat, and when Kapler asked where they were going, he replied, “To Lubyanka.”

Kapler responded, “Is there any reason for this? Have I been accused of anything? Is there a warrant against me?”31

The man said nothing. Kapler could see there was a black Packard following them. In the passenger seat, he recognized General Nikolai Vlasik, chief of Stalin’s personal security, and knew he was doomed. They drove into Lubyanka Square, where the statue of Felix Dzherzhinsky, the founder of Lenin’s secret police, the Cheka, stared across at the dreaded prison. The heavy gates of the Lubyanka swung open. The massive neo-baroque building was synonymous with the terror of the NKVD. Under the tsars it had been an insurance firm, and it still retained its imposing marbled entrance and wooden parquet floors. Below, in its labyrinthine basement, were the cells and torture chambers that had seen much service in the late 1930s.

The KGB’s infamous headquarters and prison on Moscow’s Lubyanka Square (informally known as “the Lubyanka”), where Beria had his office, still looks much as it did during Stalin’s time in power.

(Courtesy of the author)

Kapler understood that he was a top priority when Deputy Minister Bogdan Kabulov arrived. No mention was made of Svetlana. And Stalin’s name did not come up. Kapler was being accused of contact with foreigners—which was irrefutable; he knew all the foreign correspondents in Moscow—and of spying on England’s behalf.

Kabulov intoned, “Aleksei Yakovlevich Kapler, on the basis of Article 58 of our law, you are under arrest for having made known in your speeches your anti-Soviet and Counter-revolutionary opinions.”32 No trial was needed. No defense could be mounted. However, instead of the usual ten years for this offense, Kapler was sentenced to only five years in a labor camp.

Kapler’s belongings were confiscated and itemized for his signature. He was not allowed to communicate with his wife, Tatiana Zlatogorova, and certainly not with Svetlana. But Kapler was too famous to merely disappear. The war had released some tongues, especially in the military and at the front, and his arrest was a major scandal.33 Neither his epic films nor the appeals of his more courageous colleagues helped, however. Everyone knew that the cause of his arrest was his indiscreet affair with the daughter of the vozhd.

In retrospect, Kapler would say he knew that the relationship with Svetlana would inevitably end, but he was strangely enthralled. Asked why he didn’t heed the general’s advice, Kapler replied, “Who knows? It was also a question of self-respect.”34 What drew him to Svetlana was what he called “the freedom within her,” her “bold judgements.” In his mind, it was an “innocent enchantment,” not a seduction. He recognized her desperation; he felt he understood her.

Vasili’s son, the theater director Alexander Burdonsky, would later comment that Kapler was an intelligent and charming man:

Yes, he was enamored of Svetlana—when a young girl is looking at you with infatuated eyes—but he did not anticipate the outcome of all this. He had a risk-taking personality. He was ordered not to return to Moscow. He came back. He got kicked in the neck. But, you understand, this was an affair of the century that surpassed the boundaries of accepted norms. Eisenstein dreamed of making a film about it. He even wrote a script—set in a different country. He saw how Kapler suffered and he mixed himself and Kapler because he too was in love with Svetlana. All this can really thrill a man of a particular nature. Even when threats like Stalin come up.35

On March 3, Stalin arrived at the Kremlin apartment just as Svetlana was getting ready for school. Her nanny, Alexandra Andreevna, was still in the room. Apoplectic with rage, he demanded that Svetlana hand over her “writer’s” letters. He spat out the word writer. He said he knew the whole story. He was carrying their taped phone conversations in his breast pocket. “Your Kapler is a British spy,” he seethed. “He’s under arrest.” Petrified, Svetlana gave up everything Kapler had given her: letters, photographs, notebooks, and even a draft movie script about the composer Shostakovich, protesting to her father that she loved Kapler.

He turned to her nanny with withering irony, “Oh, she loves him,” and then slapped his daughter across the face. It was the first time he had hit her. “Just look . . . how low she has sunk. . . . Such a war going on and she’s busy the whole time fucking.” Her nanny managed to stammer, “No. No. No. I know her.” Stalin turned to Svetlana. “Take a look at yourself. Who’d want you? You fool! He’s got women all around him.”36 The irony that he himself had been thirty-nine and Nadya sixteen when he’d fallen in love with her was lost on Stalin.

Svetlana was in such shock that it took her a moment to realize that her father had called Kapler a British spy. She was appalled. She knew what this meant. When she returned from school that night, Stalin was in the dining room reading and tearing up Kapler’s letters. “Writer!” she reported him saying. “He can’t write decent Russian! She couldn’t even find herself a Russian.” Svetlana believed that in her father’s mind, “the fact that Kapler was a Jew was what bothered him most of all.”37 She made no attempt to contact Kapler. She knew she couldn’t even speak to his friends without its being reported to Stalin, and Kapler’s fate would be worse. She now understood that her father “was the state.”38

Kapler was held for a year in solitary confinement at Lubyanka prison before being transferred to Vorkuta in Siberia. For the Italian journalist Enzo Biagi, he recalled the ride in the “black crow,” the prison truck in which he was accompanied by other “deviationists . . . terrorists, Trotskyites, ex–Social Democrats.” Vorkuta was the locus of a prison complex in the coal-mining center in Komi Autonomous Republic. The complex had a reputation for profound brutality and exploitation.

But Kapler’s luck held. The camp director, Mikhail Mal’tsev, who’d been appointed the previous year to turn Vorkuta into a model city, selected him, as the most famous prisoner in the camp, to be the official photographer of the city and prison complex. Kapler was designated one of the zazonniki (prisoners without borders) with permission to live and work outside the prison zone.39 Kapler soon joined the Vorkuta Musical Drama Theater, a prisoners’ collective, where he met the actress Valentina Tokaraskaya, who became his lover. In the Soviet Gulag there were always surreal distinctions that dictated survival or death.

When he’d completed his five-year sentence, Kapler was released and warned that under no circumstance was he to return to Moscow. He decided to go to Kiev, where his parents lived, but not before slipping into Moscow in the hope of seeing his wife. He stayed only two days and made no attempt to meet Svetlana. As he boarded the train for Kiev, plainclothes policemen surrounded him. They hustled him off the train at the next station. He was sentenced to another five years, this time to hard labor at a mine in Inta, also in the Pechora coal-mining basin, where conditions were brutal. Only visits by his lover, Tokaraskaya, with her food parcels kept him alive and sane.

Svetlana’s cousin Vladimir Alliluyev remembered the turmoil at Zubalovo that immediately followed Kapler’s arrest. As he put it, “Everyone was kicked out of there. Everyone got hit on their brains quite harshly.” Stalin ordered Svetlana “banished” from the dacha for “moral depravity.” Vasili was sentenced to ten days in an army prison for degeneracy. Grandfather Sergei and Grandmother Olga were sent to a ministry sanatorium for failing to intervene. The housekeeper, Lieutenant Sasha Nikashidze, who had spied on the lovers and read Kapler’s letters, was fired. Zubalovo was closed.40

When Kapler was shipped off to Siberia, Svetlana knew that her father had ordered it. “It was such obvious and senseless despotism, that for a long time I was unable to recover from the shock.”41 But Kapler’s imprisonment and the discovery of her mother’s suicide had finally “cut the soap-bubbles of illusions. My eyes were opened and I could not any more claim blindness.”42