Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

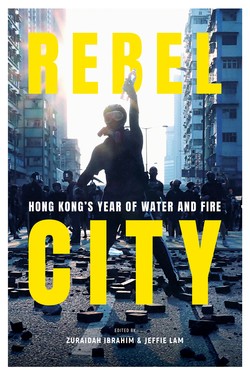

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеZuraidah Ibrahim

Through the first half of 2020, Hongkongers struggled to read one another’s mood. Surgical masks hid their faces and muffled their normally expressive Cantonese. These accessories were deemed so essential in the fight against the novel coronavirus that millions of Hongkongers ritually put them on whenever they stepped out of their homes, to protect themselves and others.

The irony was not lost on residents of the city. During the previous six months, face masks had been commonplace too. Worn by protesters to protect against pepper spray, tear gas, and surveillance cameras, masks were so associated with dissent that the government banned them – not that the injunction affected their status as de rigueur street fashion items for the autumn and winter seasons of 2019.

Just as they would during the Covid-19 pandemic, the masks made Hong Kong more inscrutable. Despite being togged in the same black attire to express solidarity with their cause, the protesters were diverse in their backgrounds, attitudes and emotions.

Most tried to show courage; many were fearful. Beyond the “yellow” camp of mask-wearing protesters too, Hong Kong as a whole became harder to recognize and decipher. It was more sullen and divided, and gripped by unfamiliar sights, sounds, and smells – brick-strewn roads, screaming matches, and acrid tear gas.

Reporting on the tumult of 2019, the adjective “unprecedented” kept turning up in our copy. Protesters’ methods grew in audacity. Their targets widened and their means became more extreme. Police escalated their use of force, from water cannons to physical beatings and live rounds. Yesterday’s shocking development became today’s new normal.

Hong Kong, which had thought of itself as vibrant and entrepreneurial but also orderly and safe, suddenly found itself on guard.

The protest movement had to develop communication networks to keep one step ahead of the police force’s feared shock troops, the Raptors. The MTR system, fully expecting that their repairs would only last until the next attack, replaced shattered glass walls with cold sheet metal. Residents wanting to enjoy city life downloaded apps to tell them which parts of town were no-go areas.

A year has passed since the demonstrations were triggered by the government’s much derided extradition bill. There is no closure to the social unrest in sight. The protests are in a suspended state, held in abeyance by a health crisis that, far from uniting the population, has further exposed its deep polarization between the pro-Beijing “blue” camp and the anti-government “yellow” – with the latter seeing the pandemic as further proof that mainland China will be the death of Hong Kong.

Conversations with protesters suggest they are at a crossroads, contemplating their next course of action. Some admit to feeling lost and lacking leadership. The criminal charges brought against hundreds have also dampened spirits. But the despair that drove the protests has not been assuaged.

With the situation in limbo, the final word on Hong Kong’s protest movement cannot be written. This book does not attempt that. What it can do is gather some of the best reporting on the crisis so far, from the perspectives of dozens of journalists who call this city home.

Through a series of detailed snapshots, we hope to give readers a fuller sense of not only the headline events of an extraordinary year, but also their behind-the-scenes dynamics, and the feelings behind the masks.

At one level, the 2019 protests were among the world’s most visible political events in history. The action could be viewed on multiple live streams. At the front lines, dozens of local and international reporters recorded the confrontations between protesters and police. Never have so many had access to what they would consider incontrovertible evidence of what exactly happened on a given day and time.

Yet, debates about who the villains and the victims were raged on. This was the Rashomon effect in the age of Facebook Live and Twitter. As in the fabled Akira Kurosawa movie, eyewitnesses came to conflicting conclusions. To many Hongkongers, police were to blame for the escalation of violence. To others, they were the thin blue line protecting the city from anarchy.

While many observers had the luxury of being both expert witness and judge, the South China Morning Post had to be more modest in our approach. First, because we have more feet on the ground and greater access to all sides than most news organizations do, we are unable to see things in simple black-and-white – or yellow-versus-blue – terms.

Second, this is our city. For most of the world’s media, the Hong Kong unrest was newsworthy largely because it was an apparent proxy war between China and the United States. For the Post, this was a local story. Most of the journalists covering the city’s affairs grew up here, fell in love, married, and are raising children here. We live among the people we report for and about, making it harder to rush to judgment.

Our journalists have strong feelings about recent events and close ties with the community. The city’s pain is our pain, its scars our own. But, collectively, the Post has tried to stick to the basics of fact-based journalism, respecting our community enough to inform it without being swayed by any ideological bias.

Of course, the Post has a firm editorial position on the larger questions facing Hong Kong. It operates within and defends Hong Kong’s press freedoms, and the special status the territory enjoys within the People’s Republic of China. In our editorials, the Post commented on the extradition law’s shortcomings, especially the need for stronger safeguards against abuse. Witnessing widespread opposition to the bill, we called for its withdrawal. We also appealed for an inquiry into police conduct, to assuage concerns on the ground; and we condemned violence by all sides. We accepted that universal suffrage, while a worthy goal, would be difficult to accomplish in the current environment.

Our primary function, though, has been to keep our readers informed. From March to December 2019, the Post published more than 4,515 articles containing the term “extradition,” plus more than 400 videos, 11 multimedia infographics and 55 live blogs. Our archive contains tens of thousands of photos and art.

This book is an edited anthology of that coverage. In some of these stories, we have left the narrative untouched. But in many others, we have gone back to the key newsmakers to have them reflect on the year that went by. Some essays go over similar ground but from different vantage points. The book does not pretend to break new ground. And there are still questions that we are unable to fully answer, like the extent of external interference in the course of events.

But the following pages do go some way in unmasking the fractured yet fluid spirit of a city going through historic change. It captures the landmark events, key debates, and the diverse cast of characters that made this an unforgettable year for all who experienced it.