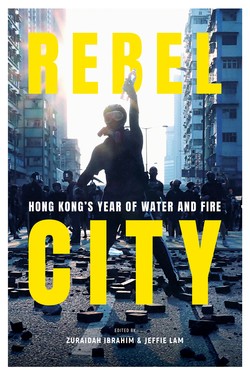

Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Top girl Carrie Lam takes a city to the brink

ОглавлениеJeffie Lam and Gary Cheung

Throughout her 13 years at St Francis’ Canossian School and its sister college, Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor was always a top girl – except once, when she came fourth in a mid-year class examination. She went home in tears that day, fearful of how her teachers and family would regard her, she revealed in a 2016 interview, just before taking office as Hong Kong’s chief executive.

Asked what she did next, Lam replied: “I took the No 1 place back.”

She shared that anecdote when recalling unforgettable low points in her life before her rise to become the city’s first woman leader. It is safe to assume that nothing in Lam’s life could have been worse than the political storm that engulfed her through the second half of 2019, when she sank to the bottom of the public’s estimation.

What began as public anger at a controversial extradition bill, which critics said could effectively remove the legal firewall between Hong Kong and mainland China, morphed into expressions of hatred toward Lam not only as author of the legislation but also as an arrogant leader who insisted on pressing ahead with it despite opposition from all quarters. It sent Hong Kong hurtling into its most serious political crisis since the former British colony returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

The combative Lam doubled down even after an estimated 1 million Hongkongers marched on June 9 to protest against the bill and demand her resignation. That turnout was double the size of a historic 2003 procession that forced the government to shelve a controversial national security bill.

Defending the legislation, Lam said a day after the march: “We were doing it and we are still doing it out of our clear conscience and our commitment to Hong Kong.” It took another protest on June 12 – which resulted in violent clashes between protesters and police, with tear gas and rubber bullets deployed and more than 80 people injured – before she said the bill would be suspended.

But the legislation was not scrapped. Angry protesters, mostly in their 20s, demanded the withdrawal of the bill and went on to stage more demonstrations, blocking major roads and besieging government offices. As the protests degenerated into violence, vandalism and intense confrontations between masked radicals and police officers, all the rules of engagement for Hong Kong’s long-standing culture of peaceful demonstrations were rewritten.

The protracted battle became an embarrassment to Beijing as the protesters made emotional appeals to Western countries, in particular the United States, against the backdrop of the US-China trade war and at the G20 summit in Osaka that June. They waved the American flag in the city, urging Washington to back a proposed Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act to give the US discretion to sanction those deemed responsible for acts that undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy from mainland China. It was approved with bipartisan support and signed into law in November 2019.

Lam faced the wrath of even loyal allies in the Legislative Council, who feared she would drag them down. Their concerns were not unfounded. In November, the pro-establishment bloc suffered a humiliating rout in the district council elections. From controlling all 18 district councils, they were left in charge of only one, retaining merely 60 out of 452 seats at stake.

What went so wrong for the top girl who became chief executive? By the end of 2019, she was viewed as a lame duck and a likely oneterm city leader. Interviews with members of her cabinet, proestablishment lawmakers and Beijing insiders suggest it was a potent combination of policy failure caused by an overconfident leader trapped in groupthink, inadequate preparation of the ground and a lack of political experience on the world stage. There was no doubt by December that heads would roll once calm returned, but whose and when remained unclear.