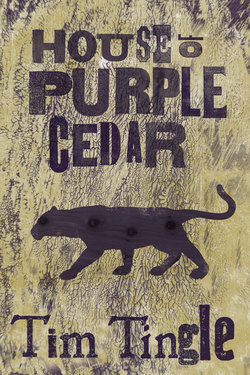

Читать книгу House of Purple Cedar - Tim Tingle - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Burning of New Hope

In my dream I was curled up on the cedar floor, next to Amafo. The icy chill of morning was gone and my cheeks now felt the sweet bath of fire. I pulled my quilt down. The fire lapped hot.

“Wake up, hon,” Amafo called, shaking me hard.

I did, but I was not at home anymore. I was at school, at New Hope.

“I musta been dreaming,” I said, stretching and yawning.

“Wake up! Get up, hurry!” Roberta Jean leaned over me hollering. Smoke swirled about her head. “Fire! Everything’s on fire!”

I was on my feet and we started running, our blankets wrapped around us. We shouldered down the stairs with the other girls. The teachers pushed us aside and ran upstairs against the flow.

“Is everybody out? Is everybody safe?” They said it over and over, but no one answered. We all just ran.

Once outside, I stood clinging to Roberta Jean, shivering and watching the skeleton of our schoolhouse crack and fall, bone by bone. It finally heaved a shuddering breath and fell into itself. A flock of small flaming boards flew in our direction. We dashed to the woods, brushing embers from our blankets.

This was not the fire I knew. There was nothing warm and calming in those yellow and blue flames. I was watching ice, cold bitter ice, come to life, rising from the frozen flames to claim our school.

We were driven by fire to freeze in the ice.

“Lillie! Lillie! Lillie!” The calls rang out through the mad darkness and fiery light. “Lillie!”

“Why does that lady keep screaming Lillie’s name?” I asked, covering my ears. “Make her stop.”

“It’s her mother,” said Roberta Jean.

“Then she knows Lillie can’t hear her.”

Those words floated back at me and I heard them for the first time. I stared at my own breath. Beyond my breath I saw the flames, like flicking and mocking tongues.

Lillie Chukma, good Lillie, was deaf.

She could not hear her mother.

She could not hear the calls to leave the building.

She slept like the seven-year-old baby that she was.

So watchful and eager to please––so very, very deaf.

I dropped my jaw and my face quivered. I tried to scream. Tears flew down my cheeks, tears that will never stop flowing till I see her at Judgment Day and wrap my arms around her. I will tell her how sweet she was and is and how much I loved seeing her every morning, how much I loved kneeling by her bed for prayers each night.

“Lillie,” I finally sputtered when I had the breath to sob.

Roberta held me closer and we pulled the blankets over our heads. Our knees shook and buckled and we drifted to the ground to sit in the melting snow, a dark green cone of wool and skin and bones and life while all around us swirled children and teachers and Nahullos and Choctaws and Cherokees and Christians all. But their running meant nothing.

Death by fire had claimed Lillie Chukma.

It was the Bobb brothers, Efram and Ben, who lifted the rafters from our fallen, smoking room and found Lillie’s body. Efram raised the roof while Ben kicked aside the still-burning boards to find her charred and fetal-tiny body. They gave it over to the Reverend Henry Willis and he carried Lillie Chukma to her mother.

Roberta Jean tugged me after her and we shuffle-stepped to stand behind Mrs. Chukma. She took her daughter, Lillie Chukma, took her in her outstretched arms, all the while staring at Reverend Willis. Finally her gaze settled on her baby. When she spoke, her words spoke the night.

“A mother should not have to bury a child.”

This tiny scene was played out for only a few of us. The rest were running to render aid, only to feel the biting flames that claimed our school. My chest hurt and my lungs ached. I knew that something truly was breaking apart as I stood and watched, wounded by the biggest loss of my life, the loss of New Hope Academy for Girls.

We turned our backs on all of this and walked as the unseen dead might walk. Through smoky fog we walked, Roberta Jean and I, floating against the stream of urgent runners, drawn to their own drowning vision of hope. We wrapped our arms around each other’s waists, muted by our grief.

We returned to our small encampment and wrapped the blankets over our heads. We fell to the moist ground and went to grabbing and clutching at each other, first our hair, yanking and pulling, angry pulling, on whatever gave good holding place, arm or foot or ear or skin of thigh. We clinched our fists and flailed away, crying loud and biting even, all the while knowing we did so in the name of love, the only love still granted us in this the most perverse of bleeding worlds.