Читать книгу House of Purple Cedar - Tim Tingle - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Note Before the Reckoning

Rose • Winter of 1967

The hour has come to speak of troubled times. Though the bodies have long ago returned to dust, too many ghosts still linger in the graveyards. You are old enough. You need to know. It is time we spoke of Skullyville.

I was born and raised in the Choctaw town of Skullyville, where I attended New Hope Academy for Girls—till it burned on New Year’s Eve, 1896. My grandmother went there too. She met my grandfather when he was a student at nearby Fort Coffee School for Boys. By the time Oklahoma became a state, all of downtown Skullyville had burned. The stores, the businesses, the stagecoach stop, all burned. We knew Nahullos set the fires. They wanted us gone.

Almost everyone from that time is dead now, their faces blurred, their stories scratched like formal words in old, old letters.

But once we were alive, all of us, and when good people, Choctaw and Nahullo both, step over our Skullyville graves, we sing as best we can, we sing those old hymns and songs, for they were everything to us. Our religion, our joys, even our sins, they all made up the music. We Amen! at the top of our lungs beneath the brush arbors, we sweat and toil in our gardens and fields and brood over our livestock and our babies both.

I am speaking as a dead one now, and soon I will be. No time to waste. This story must be told. To see not only the unfolding of events but the meaning I ascribe to them, you must know of the vision, for the house of this story is built upon my vision.

The dream came sometimes once a week, sometimes not so often, and always in the deepest hour of night, when neither day’s end nor dawn cast any light. This vision that I thought was a nightmare began when I was twelve years old. Though many years passed, in the vision I am always twelve, always sitting in the same church pew, always with my family in what at first appears to be a normal Sunday morning.

Pokoni, my grandmother, has not yet entered the church. I am saving her a seat next to me near the window, where we can both stare out at the swaying trees. Brother Willis reads the scripture in that ponderous tone of his, before he lurches into a sermon “likely to raise the dead,” as Pokoni always said.

When Pokoni appears, she walks past our row and approaches the altar, ignoring all else and staring at the wooden wall behind the pulpit. Soon everyone is following her gaze. Even after years of witnessing, I am still startled at the strangeness of the sight.

A man, and I thought I might never know who it was, is slumped over and hanging, his clothing nailed to the back of the church. His body is slowly writhing, his head lifts with every breath, and his vacant eyes return our stare. Always when you thought you knew who hung before you, then you saw another.

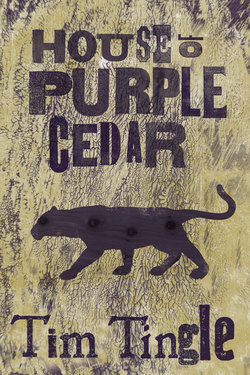

Brother Willis steps aside and Pokoni continues walking, but she now becomes a panther, black and silky-skinned, and now she is my Pokoni, then the panther once again.

Through all the days of death and suffering, I longed to see the face of this writhing one, nailed to the cedar planks of our church.