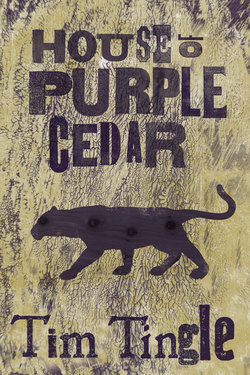

Читать книгу House of Purple Cedar - Tim Tingle - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSunday Morning

Rose

The road to the church was the color of a roan horse, lined with tall pines, deep green and sweet to smell. It seemed every Sunday a breeze caught the tops of the pines just as we rounded the last curve in the road, just before the church appeared in the clearing up ahead. Those green pine trees bowed and waved to everybody passing below.

“God’s welcome to His children,” Pokoni always said.

Every Sunday morning two hundred Choctaws drove their wagons down that dirt road on their way to the First Christian Church of Skullyville. On the Sunday following my grandfather’s hurtful injury, it was twice that many at least. The church was nestled in a clearing surrounded by a tight cluster of pines, elms, oaks and sagging sycamores. The trees to the east of the church were trimmed back and the undergrowth cleared, owing to their closeness to the graveyard. To the south and west, smaller redbuds, flame-leafed sumacs, and thorny wild roses grew unchecked.

After what happened at the train station, the Amafo I thought I knew would have stayed far away from people for at least a month. But this new Amafo, the Amafo born at the station and brought to life at our home last night, insisted that our family be the first to arrive. As we passed beneath the final clump of pines, Amafo took off his glasses, cleaned the lens, and squinted at the sky.

“Take some getting used to,” said Pokoni. I expected Amafo to nod or speak in any of a hundred ways to agree, something like “Umm,” or “uh-huh,” something oldmanish.

Amafo said nothing. He stared at the back of Pokoni’s neck till she reached behind herself and took his hand. Take some getting used to passed as everyday talk, but Pokoni was not talking about the broken glasses. She was talking about the broken world we were now slipping into.

As we neared the church, I saw a recently formed grouping of families, old to our congregation, but new in their ways. The social order of the church had changed since the New Hope burning. We now had in our midst a family of people who had all lost children in the fire.

This gathering grew every week, as grievers gave way to their grieving. They had settled on a roosting place, a comfortable spot in the shade of the elms near the graveyard. To an outsider, the grieving ones might look like a family of real kin, hovering around the graveyard for the anniversary of somebody’s death. But for those of us who knew them, their usual selves, we stared to see the changes.

No one laughed, not anymore. No one looked at anyone when they spoke. No one grabbed a friend by the waist. People touched, but not like before. Women and girls quietly stroked each other’s hair. Among the grieving men and boys, brothers and fathers to the dead girls, talking gave way to shoulder squeezing and lengthy handshakes.

My father reined Whiteface to a slow walking halt in the shade of two old oaks. Morning service was still an hour and a half away.

Amafo gripped the side rail of the wagon and swung himself to the ground. Whiteface whinnied and neighed. As Dad tied the reins to a tree, Amafo pulled his hat low and stepped into the woods. Moments later he reappeared in the midst of the grieving ones. Pokoni gripped my hand and we both watched him move among his new brethren. Slow and slower still, he lost himself among them.

My eyes teared up to see him stooped and hollowed through with sadness, but Pokoni only smiled and said, “Sweet child, you ’bout to see why I love your ’mafo so. Stop your tears and watch.”

Amafo soon stood before Amelia Chukma, Lillie’s mother. He took her hands, both hands, and held them for the longest time. Though she had not been at our last night’s gathering, Mrs. Chukma knew the all of it. Her mouth dropped to see the bruises on my Amafo’s face. She shook her head and smiled a sweet and tender smile.

Her hand seemed to lift apart from her will, as if awakening from a dull, numb sleep. Her fingers softly sketched the purple lines and swollen flesh of my grandfather. She gently moved her fingertips across Amafo’s face.

I watched a leaf fall, swaying back and forth. In one movement, Amafo lifted his palm to Amelia’s head and guided her to his shoulder. In the thin arms of Amafo, Mrs. Chukma started slow, as if feeling her way at it, then she shook and sobbed––deep, long wailing sobs.

At first the fellow mourners ignored this loud intrusion, but soon they turned to look. One by one they moved to comfort, some to Amelia, some to their own wives, some to quiet the fears of their still-living children. The wailing cry we needed came bursting forth. A graveyard cry was not enough, not for this scorching act.

This was the final day the mourners gathered by themselves.