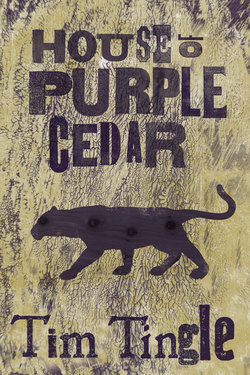

Читать книгу House of Purple Cedar - Tim Tingle - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеReverend Willis & the Boys

Young Rose • January 1896

I always feared death by ice. Much more than death by fire. Even as a little girl listening to Brother Willis preach about how the world would end, I was never afraid of fire, of burning up. Fire was warm and if it got to be too hot, you just scooted away. The only real problem with fire was starting it in the morning. Everybody else was asleep, and you had to climb out of bed and freeze your fingers fetching firewood so they could stay curled up and comfy.

“Rose, are you up yet?” Momma said every morning, while the moon still shone and the sun hadn’t even thought of waking up. The walls in our house were so thin, she never had to shout.

“Is it morning yet?” Daddy asked, and I could hear him roll over. I knew he covered his head with his pillow to block out the coming day.

“It will be soon,” Momma always said. “No need to waste it.”

No need to waste it meant they could sleep for half an hour longer, but I better get up and start the morning fire. My grandma and grandpa, Amafo and Pokoni, lived with us too. I guess it’s better said we lived with them since this used to be their house. Daddy liked to tell about cutting the cedar and sawing the boards, helping Amafo build this house when he was still a boy.

“I was just a neighbor kid, but I knew if I was a good worker, he’d let me court your mother someday,” my father used to say. My little brother Jamey always made a secret face when he heard this. But there were no secrets, not from Momma.

“You don’t want to be like those lazy Willis boys, do you, Jamey?” she’d say. “They get whippings sometimes. You don’t want a whipping, do you?”

Course that never happened to me or Jamey, neither one. We never got a whipping. But the Willis boys did––and always by their momma––never by their preacher daddy. I never liked seeing anybody get whipped, but especially not the Willis boys. I know they gave living Hades to their big sister Roberta Jean, but there was just too many of ’em to expect anything good, and the how many of them there were, that wasn’t their fault.

“Even a good man, a preaching man, brings troubles on himself sometimes,” Pokoni used to say, shaking her head at the Willis boys.

I remember her saying that very thing one Easter Sunday when the boys stole the baby Jesus from the packed-away Nativity box. They buried him in the graveyard by the church to see if he would rise from the dead during the service. While Brother Willis was telling about how the stone was rolled away, seven-year-old George Willis started hollering.

“Jesus lives!” he shouted. “He’s coming outta the ground right now! Everybody come see!”

What those boys saw was a skunk stirring up leaves around the baby Jesus gravesite, but they didn’t know it. They all scrambled out the windows yelling louder than their daddy ever did. Blue Ned Willis was five at the time, and he chimed in with, “We’re going to meet Juh-eeee-sus!” He said it over and over again, sounding more like his daddy every time.

The older boys saw Jesus first and were able to stop, but not Blue Ned. He plowed right ahead, stepping over the rise of graves, dodging tombstones, till he learned a life lesson he would never forget. One of the world’s ugliest sites is the close-up view of a skunk’s backside. With the tail raised.

The skunk sprayed young Blue Ned with a cloud that could be seen––and smelled––from all the way inside the church. Blue Ned rolled on the ground, rubbing his eyes and crying. As the skunk disappeared into the woods, his brother George remarked, “Jesus just wants to be left alone, look like to me.”

Reverend Willis simply prayed a closing prayer and waited by his wagon, his head bowed and clutching his Bible, while the Bobb brothers and Mrs. Willis handled the situation. Older brother Samuel, sitting on the front pew with his mother, never even turned his head to see what trouble his brothers were causing. He soon joined his father on the buckboard.

We had been married for over forty years, Samuel Willis and I, and were visiting what was left of Skullyville one Sunday afternoon. He told me how later that evening, during one of his night walks, he found a rope and a burlap sack in the woods by the cemetery, the sort of sack one would use to tote a skunk. Someone, out of meanness, had planted that skunk to disrupt our Easter worship service. The memories came flooding back and we shook with laughter, a very hard thing to do, seeing how the woods had reclaimed our once fine community.

“My daddy thought he would never get the congregation back. Every time he spoke the word Jesus…”

“In that booming voice of his…”

“I can hear him now…”

“Wish we could…”

“Someone would start coughing…”

“To cover up their laughing.”

“But he did it,” Samuel said. “Oh yeah. He did it. He brought us back. I don’t know who laughed that final laugh. I was too scared to turn around. I knew how mad he was getting, Sunday after Sunday. My father leaned over the pulpit and told us all, ‘Make your choice. Either get up and follow that Hell-bound skunk to the woods or let Jesus return to his church, but don’t be stinking up this temple with your laughter when his Holy name is spoken!’ Nobody laughed after that.”

I thought Samuel was about to break out in tears when we came to the clearing where the church used to stand, where his daddy was buried, but he didn’t. Samuel just looked at the well-kept graves for the longest time.

“I never thought they would burn the church,” he finally said.

"At least the church was empty,” I replied. “The school was full of girls.”