Читать книгу House of Purple Cedar - Tim Tingle - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNight Gathering

By the time I eased the wagon into the barn and unhitched Whiteface, I think every Choctaw within fifty miles of Skullyville knew about Marshal Hardwicke striking Amafo. That evening more people crowded into our living room than ever before, some families who had not visited our home in years. The McCurtains, the Folsoms, folks who held high positions going all the way back to Choctaw days in Mississippi.

Brother Willis and his family were there, of course, with his oldest son Samuel, and several used-to-be shopkeepers, who always seemed to be talking about rebuilding their stores. They never recovered after the burnings. Many families had also lost their barns to nighttime fires.

“It’s not the work that keeps everybody from rebuilding,” Pokoni often said. “It’s hard to find the will to start up again after you’ve lost everything.”

“And the fear,” I once heard Amafo say.

Pokoni was dashing to and from the kitchen, trying her best to keep everyone’s cups and bowls filled with hot coffee and steaming pashofa corn soup. Amafo found himself a spot on a step halfway up the stairs to the second floor. He barely moved a muscle, holding his coffee cup with both hands and softly blowing. His hat was pulled low over his eyes, discouraging anyone who might try to draw him into a conversation.

To some, he might seem to be sleeping, but not a word escaped Amafo’s attention. The stakes were high. We were all Skullyville Choctaws, and our lives were threatened by what had occurred.

I learned much by watching Amafo that night. To the hotheaded young men he was as meaningless as a tree stump—an old man whose youth and usefulness were a thing of the past. I saw Amafo bide his time, allowing one argument after another to fizzle and die.

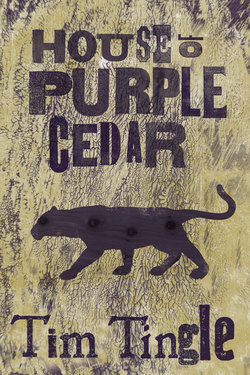

He already knows what he’s going to do, I realized. He will wait all night if he has to, till everyone else has burned themselves out, before he tells us what he’s thinking. For the first time, I saw a Choctaw elder at work. And I understood—for the first time—why our way is a powerful way. It is a way of waiting and watching, and Amafo was as wise in the ways of survival as a great black cat of the woods.

I was determined to stay up and see what Amafo would do. I set about helping Pokoni. We washed empty cups, of coffee and pashofa both, refilled them and returned them to our guests before they knew they were gone. All this we did without a word between us.

The hours dragged on. It was approaching midnight when I heard Mister Yeager cough, like he always did when he had something to say. He had spent his younger days chasing bootleggers with the Lighthorsemen, our Choctaw posse. “Sure we are peaceable folks,” he said. “We’re churchgoers, all of us, and we gonna do the Lord’s will, best we know it.”

He nodded in the direction of Brother Willis, with a tone of embarrassed humility. Brother Willis appeared not to respond. But if you watched him after everybody else had looked away, you saw him take a deep breath and look into his coffee cup with sad eyes.

I was carrying a tray of coffee cups from the living room to the kitchen, where Pokoni was washing with a fury. When Mister Yeager spoke, she dried her soapwater hands on her apron and moved to the doorway to listen.

“I’m just saying we ought to keep our guns near our bedsides,” he said. “We got to protect ourselves from the Nahullos, all of ’em. We can’t let our guard down.”

I sat the tray on the kitchen counter and asked Pokoni, “Why would they want to hurt us? It was a Nahullo that hit Amafo.”

She leaned towards me and whispered, “Hon, listen good to what I’m telling you. People who are bullies are driven to punishing those they have harmed the most. And the bullying will usually get worse.

“Look around you. These Choctaw families are gathered together at our house for safety. By the time the marshal and his friends spread their talk about what happened at the train station, every Nahullo in Spiro will be fussing and fuming. More than likely they gonna blame us, hon. But the real thing we got to worry about is this. Choctaw hotheads, that’s where the real danger is. All Choctaws are not like your grandfather.”

She stepped to the sink, saying, “Now. I’ll wash, you dry, and let’s make up for lost time.”

Ten minutes later my nineteen year-old cousin Wilbur burst through the front door. “We know where the marshal lives,” he shouted. “Let’s see how he likes a board upside the head.”

Everybody grew nervous thinking about Wilbur taking a board to the marshal. They knew the marshal would kill him and go unpunished.

My grandmother looked at me.

“If we’re going to town, we better bring guns,” said Wilbur’s little brother Zeke, who had just celebrated his fourteenth birthday. I saw my grandparents trade glances to hear Zeke talk so brave.

The older folks just let the young ones go on with their blustery talk. Even when they called for guns and warring, Amafo kept his hat low and sipped his coffee. Their words, he knew, would fall like hot embers on a coldwater lake. But other words, spoken by elders, caught Amafo’s attention—and Pokoni’s as well.

Mister Pope, a neighbor and a good man for shoeing horses, said, “Maybe we all should stay here, camp out here. We’d be here to protect your family. They wouldn’t dare try anything if we was all here.”

“I’ve got nothing to do that cain’t wait. I’ll be glad to,” someone said.

“We’ll all be here if any trouble comes,” Mister Pope said. “I’ll drive into town tomorrow and buy enough ammunition for us all. Shells, gunpowder. We’ll divey it up and reckon the money later. I’ll keep good account of everything.”

Hearing this, Amafo lifted his hat and looked at Pokoni. Pokoni filled a coffee cup to overflowing and crossed the room to hand it to Mister Pope.

“Here’s a fresh cup for you,” she said. Mister Pope took the cup without looking at it and promptly spilled it on himself.

“Yow,” he hollered, dropping the cup and splashing hot coffee all over his britches. His wife ran to his aid. In the laughter that followed, everyone seemed to forget his idea of a makeshift army, an invitation to trouble. Truth was, our yard was already overrun with an army, the army of Colonel Tobias Mingo.