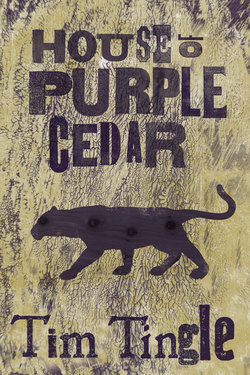

Читать книгу House of Purple Cedar - Tim Tingle - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGoode Kitchen and Strong Women

Rose

Twenty women—wives and kinfolks to the men in the living room— crowded around the kitchen table. While Pokoni and I washed dishes and served the men, they kept us going. They cut corn from the cob, chopped chicken for pashofa, and refilled coffee water boiling on the stove. Their talk circled the affair at the train station, viewing it in a corner-of-the-eye way of talking. Though armed with butcher knives and long-handled spoons, their real weapons were words, and they knew how to use them.

“There’s no telling what Uncle Lester would have done if he was still alive. Mercy, did he have a temper.”

“I believe the marshal’s wife would be shopping for a black dress, Lester have anything to do with it.”

“He was not afraid of nothing or nobody.”

“Uh-huh. He remind me of that Wilson boy, what was his name? ’Member, the one went in the army. Took after a officer with a pickaxe. Man made him work in the kitchen and he hit him with a pickaxe.”

“Nothing good came of that.”

“I ’spec he still in jail.”

“Somewhere back east.”

“Nord Caylina, I believe.”

“How’s the water looking?”

“Need refilling, look like to me.”

“Gonna need another chicken ’fore long.”

“With all the noise coming from in there, you’d think they wouldn’t have time to eat.”

“They men. They gonna find time to eat.”

“You know that’s true.”

“Un-huh.”

“They gonna get to the table.”

“I believe that.”

“Last time my man went to battle, it was over a drumstick.”

“Tell me about it.”

“Here come the soup pot. Look like somebody done licked the bottom of it.”

“Must be my husband.”

“Could be mine.”

“Yessir. They men. They gonna find time to eat.”

“You know that’s true.”

With the children nestled around Colonel Mingo’s campfire, the men going at it in the front room, and the younger ladies helping Pokoni in the kitchen, the older women roosted comfortably on the back porch, bathed in the blue light of the waning moon.

The sounds amongst these women were creaking sounds, the creaks of a rocking chair, the soft creaks of porch planks as tired bodies shifted and settled. Every gust of wind carried earthy smells, of hay and chickens, sometimes the perfume of gardenias.

These older women seemed to float in a different world, a place of whispery music and faded colors. It was a place not between life and death, but rather above life and death, above it all. The calls to action and urgings from the living room, they had no place here. They were fires from a distant hillside. When these women spoke of the men in the house, they spoke of them as if they were children.

“The marshal will pay. He will suffer—and his kind, they will all suffer,” a deep voice boomed from the living room.

“That sounds like Bobby Harris, little Bobby Harris,” said Mrs. McVann, puckering her lips in soft laughter. “I still remember him begging me for a piece of blackberry pie. He saw it sitting on the kitchen table and went to almost crying, chubby little Bobby Harris.”

“Wasn’t he a whiney boy?” said Mrs. Mangum.

“He will suffer,” another man repeated.

The word suffer unsettled the women. The lid of a memory box rattled open and threads of hymns came pouring out. The women started singing to themselves, till one single voice stood out. It was cracked and wavering. The other women fell silent and the eldest woman sang.

Hatak yoshoba chia ma!

Achukmut haponaklo;

Chisus chi okchalinchi ut

Auet chi hohoyoshke;

Chisus okut

Auet chi hohoyoshke.

Hark the voice of love and mercy,

Sounds aloud from Calvary.

See it rends the rocks asunder

Shakes the earth and veils the sky.

“It is finished, it is finished,”

Hear the dying Saviour cry.

Somebody picked up a turtle shell rattle I’d left lying on the porch and started shaking it. The sound was so soft. Those little stones shifting around in the turtle’s home made everything around it glow in the color of holy. It was a yellow and blue color, like peeking through rainclouds at a tree-shaded lake shining in the sky.

Holy, holy, holy.

Seeing those old women sitting on the porch.

Holy, holy, holy.

Those old women made it so. Everything was holy. The creaking boards, the wind tilting the tops of the pine trees, the smell of gardenias, the cold silver stars, everything was holy.

Around one o’clock in the morning, the conversation wound down to a light sprinkling. I could hear the loud clicking of our grandfather clock. It sat by the staircase wall of the living room and its quiet noise always filled the house after everyone went to bed.

This was farming country and Saturday had been a working day like any other. Droopy eyes blinked and tired heads went to nodding. Snoring came from every corner.

At one-thirty, Pokoni moved slowly to the living room and settled back in her usual chair facing the empty fireplace. She closed her eyes and when Amafo rose to heat milk for her cocoa, she merely tilted her head in his direction. In a few minutes the sweet smell of scalding milk drifted from the kitchen. Amafo appeared carrying grandmother’s cocoa cup, stirring the chocolate to life as he walked. She opened her eyes and accepted the steamy drink.

Amafo moved to the center of the room and stood before the fireplace. The snoring ceased and slumping men sat up. The front door eased open and several men entered, heads down and tip-toeing. The kitchen emptied and women stood side-by-side with their husbands. The vigil, they knew, would soon be over.

“I need your help,” my Amafo said, and a room full of anxious eyes turned his way. “You have every one of you been very nice to offer to help me and my family. I accept your offer.”

“You say the word, we’re ready,” said Cousin Wilbur. Mister Pope scooted behind him, leaned over and placed one large hand on Wilbur’s shoulder, letting the young man know it was time to listen.

“Marshal Hardwicke expects me to stay far away from town. And if I did, this would all be forgotten. But I will never forget this day and my grandchildren will never forget this day.”

Amafo took his glasses off and held them up for all to see.

“It is the day my glasses were broken. But maybe it will be a day of blessings after all. Maybe now the people of Spiro can see, as we have seen for years, the man who is their marshal.”

Amafo was tiring now, fading rapidly. His face sagged and he sat down on the ledge of the fireplace. Pokoni reached out and touched him on the knee, and a new breath of energy seemed to fill him. He lifted his head and gazed open-eyed around the room.

“We must all agree to do this, all of us. I need your help,” he said. “Many of you work for Nahullos. They gonna try to talk to you about today. Don’t fall into that trap. They gonna ask about the marshal, what you think of the marshal, what he did to that old Choctaw man at the railroad.”

Amafo stood up real slow and pulled the hat from his head like he was wiping his brow. The right side of his face, where the board struck him, was deep purple. Even from where I stood I could see broken blood vessels snaking off from the main wound. His eye was swelled shut. A line of dried blood as thick as a bacon slab ran down his cheek.

I gasped and a hot breath of air flew from my chest. Murmurs floated around the room and several husbands and wives moved closer to touch and hold one another. Pokoni blinked several times and thrust her chin up, making sure she held her head high. I knew she was fighting back the tears.

This was Amafo’s moment and tears would do him no good.

“When they try to talk to you ’bout it, just walk away,” Amafo said. “If you got to say anything, tell ’em how tough you think the marshal is. Tell ’em how you’d never want to cross him. Tell ’em he is a big, strong man. Then walk away.

“They will talk after you leave. They will tell stories about today. More people than the railroad platform could hold will claim to have seen it all. Everyone will talk about Marshal Hardwicke. And when the talk dies down, I will always be there, wearing my spiderweb glasses.

“They will see a lot of me in town. I will cross the street to speak friendly words to the marshal. I will do this. Over and over I will do this, every day I will do this, speak friendly words to him and tip my hat to him, till one day he will turn away from me and they will see who is afraid. That is how we will win. Our enemies will be defeated by our goodness.”

“Now, this day is over and the Lord’s Day is upon us,” he said, replacing his hat. “You are all welcome to stay. Goodnight and God bless you. Yakoke. You are my friends.”

Amafo helped my grandmother from her chair and the two of them made a slow procession up the stairs. Lamps were blown out throughout the house, women brought blankets and pillows in from the wagons, and within ten minutes an entire household of Choctaws nuzzled in the warm clutches of sleep.