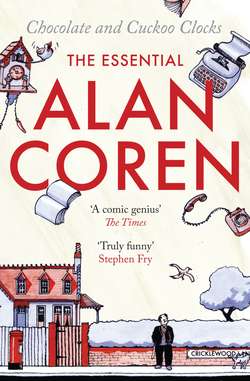

Читать книгу Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks - Alan Coren - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

Under the Influence of Literature

My mother was the first person to learn that I had begun to take literature seriously. The intimation came in the form of a note slid under my bedroom door on the morning of February 4 (I think), 1952. It said, quite simply:

Dear Mother,

Please do not be alarmed, but I have turned into a big black bug. In spite of this I am still your son so do not treat me any different. It must have happened in the night. On no account throw any apples in case they stick in my back which could kill me.

Your son.

I hasten to add that this turned out to be a lousy diagnosis on my part. But the night before I had gone to bed hugging my giant panda and a collected Kafka found under a piano leg, and since, when I woke up, I was flat on my back, it seemed only reasonable to suppose that I’d metamorphosed along with Gregor Samsa, and was now a fully paid-up cockroach. The fit passed by lunchtime, but for years my father used the story to stagger people who asked him why he was so young and so grey.

Thing is, I was pushing fourteen at the time, and caught in that miserable No-Man’s-Land between Meccano and Sex, wide open to suggestions that life was hell. My long trousers were a travesty of manhood, and shaving was a matter of tweezers and hope. Suddenly aware of how tall girls were, and of how poorly a box of dead butterflies and a luminous compass fit a man for a smooth initiation into the perfumed garden, I tried a desperate crash-programme of self-taught sophistication; I spent my evenings dancing alone in a darkened garage, drinking Sanatogen, smoking dog-ends, and quoting Oscar Wilde, but it never amounted to anything. Faced with the Real Thing at parties, I fell instant prey to a diabolical tic, stone feet, and a falsetto giggle, and generally ended up by locking myself in the lavatory until all the girls had gone home.

Worst of all, I had no literary mentors to guide my pubescent steps. For years I’d lived on the literary roughage of Talbot Baines Reed and Frank Richards, but the time had now come to give up identifying myself with cheery, acne-ridden schoolboys. Similarly, the dream heroes of comic-books had to be jettisoned; I could no longer afford to toy with the fantasy of becoming Zonk, Scourge of Attila, or Captain Marvel, or the Boy Who Saved The School From Martians – girls weren’t likely to be too impressed with the way I planned to relieve Constantinople, it had become increasingly clear to me that shouting ‘SHAZAM!’ was a dead loss, since it never turned me into a muscle-bound saviour who could fly at the speed of light, and as for the other thing, my school seemed to pose no immediate threat to Mars, all things considered. I needed instead, for the first time, a reality to build a dream on.

But I wasn’t yet ready for adult ego-ideals. Not that I didn’t try to find them in stories of Bulldog Drummond and the Saint (Bond being, in 1952, I suppose, some teenage constable yet to find his niche), but experience had already taught me the pointlessness of aiming my aspirations at these suave targets. Odds seemed against my appearance at a school dance, framed in the doorway, my massive bulk poised to spring, my steely eyes flashing blue fire, and my fists bunched like knotted ropes. Taking a quick inventory, I could tell I was short-stocked on the gear that makes women swoon and strong men step aside. And, uttering a visceral sigh (the first, as things turned out, of many), I sent my vast escapist, hero-infested library for pulping, and took up Literature, not for idols, but for sublimation.

The initial shock to my system resulting from this new leaf is something from which I never fully recovered. Literature turned out to be filled, yea, even to teem, with embittered, maladjusted, disorientated, ill-starred, misunderstood malcontents, forsaken souls playing brinkmanship with life, emaciated men with long herringbone overcoats and great, staring tubercular eyes, whose only answer to the challenge of existence was a cracked grin and a terrible Russian shudder. I learned, much later, that there was more to Literature than this, but the fault of over-specialisation wasn’t entirely mine; my English master, overwhelmed to find a thirteen-year-old boy whose vision extended beyond conkers and Knicker-bocker Glories, rallied to my cry for more stuff like Kafka, and led me into a world where bread fell always on the buttered side and death was the prize the good guys got. And, through all the borrowed paperbacks, one connecting thread ran – K, Raskolnikov, Mishkin, Faust, Werther, Ahab, Daedalus, Usher – these were all chaps like me; true, their acne was spiritual, their stammer rang with weltschmerz, but we were of one blood, they and I. How much closer was I, dancing sad, solitary steps in the Stygian garage, to the hunter of Moby Dick, than to Zonk, Scourge of Attila!

At first, I allowed the world which had driven me out of its charmed circles to see only the outward and visible signs of the subcutaneous rot. In the days following my acute disappointment at not being an insect, I wandered the neighbourhood dressed only in pyjamas, a shift made from brown paper, and an old overcoat of my father’s, satisfactorily threadbare, and just far enough from the ground to reveal my bare shins and sockless climbing boots. By opening my eyes very wide, I managed to add a tasteful consumptiveness to my face, backed up by bouts of bravura coughing and spitting, and I achieved near-perfection with a mirthless chuckle all my own.

Suburban authority being what it is, I ran foul of the police within a couple of days, not, as I’d intended, for smoking reefers or burying axes in pensioners’ heads to express the ultimate meaninglessness of anything but irrational action, but for being in need of care and protection. At least, this was how a Woolworth’s assistant saw me. I had been shuffling up and down the aisles, coughing and grinning by turns, when a middle-aged woman took either pity or maliciousness on me, and tried to prise an address from the mirthlessly chuckling lips.

‘What’s your name?’ she said.

‘Call me Ishmael,’ I replied, spitting fearlessly.

‘Stop that at once, you horrid little specimen! Where do you live?’

‘Live!’ I cried. ‘Ha!’ I chuckled once or twice, rolled my eyes, hawked, spat, twitched, and went on: ‘To live – what is that? What is Life? We all labour against our own cure, for death is the cure of all diseases …’

I took a well-rehearsed stance, poised to belt out an abridged version of La Dame Aux Camélias, when the lady was reinforced by a policeman, into whose ear she poured a resumé of the proceedings to date.

‘Alone, and plainly loitering,’ said the copper. He dropped a large authoritarian hand on my shoulder. I was profoundly moved. I had been given the masonic handshake of the damned. Already with thee, in the penal settlement, old K.

‘I shall go quietly,’ I said, wheezing softly. ‘I know there is no charge against me, but that is no matter. I must stand trial, be condemned, be fed into the insatiable belly of the law. That is the way it has to be.’

I gave him my address, but instead of leading me to the mouldering cellars of the local nick, he took me straight home. My parents, who hadn’t yet seen me in The Little Deathwisher Construction Kit, reeled and blenched for long enough to convince the constable that the fault was none of theirs. My father, who believed deeply in discipline through applied psychology, gave me a workmanlike hiding, confiscated the existential wardrobe, and sent me to my room. By drawing the curtains, lighting a candle, releasing my white mice from bondage, and scattering mothballs around to give the place the camphorated flavour of a consumptive’s deathbed, I managed to turn it into an acceptable condemned cell. Every evening after school (a perfectly acceptable dual existence this; the Jekyll-and-Hyde situation of schoolboy by day, and visionary nihilist by night appealed enormously to my bitter desire to dupe society) I wrote an angstvoll diary on fragments of brown paper torn from my erstwhile undershirt, and tapped morse messages on the wall (e.g. ‘God is dead’, ‘Hell is other people’, and so on) not, as members of the Koestler fan-club will be quick to recognise, in order to communicate, but merely to express. I got profound satisfaction from the meaninglessness of the answers which came back from the other half of our semi, the loud thumps of enraged respectability, unable to comprehend or articulate.

However, the self-imposed life of a part-time recluse was growing less and less satisfactory, since it wasn’t taking me any nearer the existential nub which lay at the centre of my new idols. I was, worst of all, not experiencing any suffering, but merely the trappings. True, inability to cope with what the romantic novelists variously describe as stirring buds, tremulous awakenings, and so on, was what had initially nudged my new persona into life, but this paled beside the weltschmerz of the literary boys. Also, suburban London was not nineteenth century St. Petersburg or Prague, 1952 wasn’t much of a year for revolution, whaling, or the collapse of civilisation, I was sick of faking TB and epilepsy, and emaciation seemed too high a price to pay for one’s non-beliefs. Pain, to sum up, was in short supply.

It was The Sorrows Of Young Werther which pointed the way out of this slough of painlessness. Egged on by a near-delirious schoolmaster, I had had a shot at Goethe already, since a bit of Sturm und Drang sounded just what the doctor ordered, but I’d quickly rejected it. I wasn’t able to manufacture the brand of jadedness which comes, apparently, after a lifetime’s fruitless pursuit of knowledge, and the paraphernalia of pacts with the devil, Walpurgisnachtsträume, time-travel, and the rest, were not really in my line. While I sympathised deeply with Faust himself, it was quite obvious that we were different types of bloke altogether. But Werther, that meisterwerk of moonstruck self-pity – he was me all over.

The instant I put down the book, I recognised that what up until then had been a rather primitive adolescent lust for the nubile young bride next door had really been 22-carat sublime devotion all along. It was the quintessence of unrequitable love, liberally laced with unquenchable anguish. Sporting a spotted bow, shiny shoes and a natty line in sighs, I slipped easily into the modified personality, hanging about in the communal driveway for the chance to bite my lip as the unattainable polished the doorknocker or cleaned out the drains. I abbreviated the mirthless chuckle to a silent sob, cut out the spitting altogether, and filled the once-tubercular eyes with pitiable longing.

The girl, who must have been about twenty-five, responded perfectly. She called me her little man, underlining her blindness to my infatuation with exquisite poignancy, and let me wipe the bird-lime off her window-sills and fetch the coal. What had once been K’s cell, Raskolnikov’s hovel, the Pequod’s poop-deck, now took on the appearance of a beachcomber’s strongbox. My room was littered with weeds from her garden, a couple of slats from the fence I’d helped her mend, half-a-dozen old lipstick cases, a balding powder-puff, three laddered stockings (all taken, at night, from her dustbin), a matted clot of hair I’d found in her sink, an old shoe, a toothless comb, and a pair of lensless sunglasses that had once rested on the beloved ears. Daily, I grew more inextricably involved. I began to demand more than silent service and unexpressed adulation. I dreamed of discovering that she no longer loved her husband, that she had responded to my meticulous weeding and devoted washing-up to the point of being unable to live without me. I saw us locked in each other’s arms in a compartment on the Brighton Belle, setting out on a New Life Together.

In April I discovered she was pregnant. For one wild moment I toyed with the idea of claiming the child as my own, thus forcing a rift between her and her husband. But the plan had obvious drawbacks. The only real course of action was undoubtedly Werther’s. Naturally, I’d contemplated suicide before, but an alternative had always come up, and, anyway, this was the first time that I had something worth dying elaborately for. I wrote innumerable last notes, debated the advantages of an upstairs window over the Piccadilly Line, and even wrote to B.S.A. to ask whether it was possible to kill a human being with one of their airguns, and, if so, how.

In fact, if the cricket season hadn’t started the same week, I might have done something foolish.