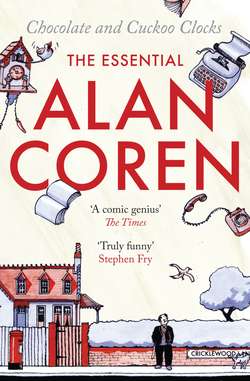

Читать книгу Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks - Alan Coren - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

Оглавлениеby Giles and Victoria Coren

Giles: So who’s going to write the introduction?

Victoria: I thought we were doing it together.

G: I don’t know. I’ve never written with anyone else. He never wrote with anyone else.

V: It’s not that hard. One person types, the other one paces …

G: And how do we refer to him? If it’s a serious essay, making a case for his inclusion in the canon, he ought to be referred to as ‘Coren’. But that would be weird, coming from us.

V: Well, we can’t write ‘Our father’. That sounds like God. ‘Daddy?’ We can’t call him Daddy. That’s just embarrassing.

G: Maybe it would be better if someone else wrote it. If we do it, it looks like vanity publishing. Any old twonk can die and have his children bind up his writing and say it’s great. Maybe we should ask an academic to do the introduction, to give it some gravitas.

V: He’d like an academic. For a long time he thought he was going to be one, after all. He spent those two years at Yale and Berkeley on the Commonwealth Fellowship.

G: And there was post-grad at Oxford before he went. And his First was a serious First. I think maybe even the top one in the year. He got the Violet Vaughan Morgan scholarship.

V: I always confused that with his medal for ballroom dancing.

G: No no, that was just called ‘the junior bronze’.

V: Do you think he’d have enjoyed being an academic?

G: Probably, but I don’t think his students would have enjoyed failing their exams because all they had at the end of term was a lot of jokes about Flaubert’s haemorrhoids, and an ability to write parodies of Trollope as spoken by two dustmen from Croydon.

V: He was brilliant, though. It’s a rare man who can go on a panel game and work an argument about the exact dates of the Augustan period in English literature into the middle of a John Wayne impression.

G: He was happier doing it in the middle of a John Wayne impression. Remember how he used the phrase ‘homme sérieux’, with a little flounce of the heel? He thought the very idea of a serious person was somehow preposterous.

V: He could have made a wonderful tutor in the 1960s, when it was about infusing students with a love of literature, rather than the rigours of critical theory.

G: But he had a short attention span. That’s also why he never wrote a novel. He had ideas for novels, but they were always flashy ideas with a great first sentence. He could never quite be bothered to sit down and write them.

V: Let’s not get an academic to write the introduction. We’ve got serious people introducing each decade anyway.

G: Serious like Victoria Wood, do you mean? Or serious like Stephen Fry?

V: They’re serious comedians. And Clive James is a heavyweight.

G: And A.A. Gill spells his name with initials, which is the sine qua non of academia. That’s better than being a Regius professor. T.S. Eliot, A.J.P. Taylor, F.R. Leavis, A.C. Bradley …

V: P.T. Barnum.

G: We still need someone for the 1960s.

V: The four people doing the later decades have written ‘appreciations’ of someone who was already quite established by then. They’re brilliant pieces. But for the 60s, it would be nice to have someone who knew him really well personally, when he was young.

G: Uncle Gus?

V: I was thinking more of Melvyn Bragg. They were at Wadham together, they’ve been friends ever since – and if you asked most British people to name an academic, they’d probably say Melvyn Bragg anyway. Or Peter Ustinov.

G: Melvyn is a big name. And he does carry intellectual weight. But he won’t get the bums on seats at readings in Borehamwood and Elstree like Uncle Gus would.

V: I’m asking Melvyn. And I think we should do the main introduction ourselves. So what shall we write in it?

G: Well, if we were going to treat him as a serious writer, we’d start with the Saul Bellow stuff. The lower-middle-class Jewish home in Southgate. Osidge Primary. East Barnet Grammar. The inspirational English teacher, Ann Brooks, who encouraged him to join the library and start reading. Growing up in the war. The mother who was a hairdresser. The father who was a … what was Grandpa Sam exactly? A plumber?

V: That’s what they said. I think it’s just that he had a spanner. He was an odd job man really. I also heard he was a debt collector.

G: And I heard Great Grandpa Harry was a circus strongman, but I doubt it was true. Harry was born in Poland in 1885 and left in 1903 before the pogroms started. A smart man is what he was.

V: Sam and Martha dreamed of Daddy being articled to a solicitor, didn’t they? That’s the other reason he loved Miss Brooks, because she went round to the house and persuaded them that he should apply to Oxford instead.

G: God, a solicitor. He’d have been so miserable. And, of course, nepotism being what it is, we’d have ended up solicitors as well. And then we’d have been really miserable too.

V: You are really miserable.

G: So then he went off to Oxford. And there was that first morning when he came downstairs in his digs and the landlady had cooked bacon and eggs …

V: He always called it ‘egg and bacon’ …

G: … she says with Talmudic precision, of the kind which crumbled in 1957 when he took the first forkful. And that was the beginning of the end, really, for all things Jewish.

V: He was always sentimental about Jews though.

G: He was always sentimental about everything. Like America.

V: He loved Yale and Berkeley … Do you think he ever actually wanted to be a don, or was he just so happy as a student that he wanted it to go on longer? Going to Oxford transformed his life.

G: Yes, but people know about all that. Not necessarily about him, but about that generation of 1950s grammar-school boys – the Alan Bennetts, the Melvyn Braggs, the Dennis Potters – that brief window between two educational Dark Ages, when a certain kind of lower-middle-class boy got a chance, went to Oxford and had a crack at the Establishment. That’s the irony of the antagonism between Punch and Private Eye later in the ’60s …

V: Exactly. Private Eye tried to mock Punch for being fuddy-duddy and Establishment, but Punch was run by the working-class boys, the grammar-school boys, the revolutionaries, while Private Eye was a bunch of right-wing, privileged public-school boys, sons of diplomats, who looked down on the staff of Punch because they thought they were common. And, in Daddy’s case, Jewish. In public, Private Eye pilloried them for being Establishment, in private Barry Fantoni was telling everyone: ‘Alan Coren looks and sounds like a cab driver.’

G: Which is why cab drivers liked him so much.

V: The Establishment is one of the things Daddy was sentimental about. He was so proud to feel part of it. And of Englishness – Keats, Shakespeare, churches, rolling hills, striding through the New Forest in a tweed cap, slashing at the ferns with a shooting stick. He actually enjoyed horseriding. And he was strangely good at it. Despite his grandfather having come over from Poland, he really did feel part of all that.

G: His proudest moment was meeting the Queen. Closely followed by meeting Princess Margaret. Closely followed by meeting Andrew and Fergie. He loved a royal. Almost as much as he loved a punctual postman.

V: But we were talking about America. He was so dazzled by it. All those hamburgers and giant steaks after the austerity of ’50s Britain. And better cars. And the literature, all those garish 1960s paperbacks of Augie March and On The Road. He started sending pieces to Punch from there, and they offered him a job so he chucked in the academic plans, came home and went to work in Fleet Street. El Vino’s, Punch lunches, Toby Club dinners, fellow writers, the old Punch table, the line of editors going back to 1841, he loved it all.

G: It was strange reading back through those first pieces from the 1960s. The fledgling him. You can see what was coming in a piece like ‘It Tolls For Thee’, a domestic comedy about trying to get a phone installed. But the writing is politically engaged, he was still taking things seriously – like racism in ‘Through A Glass, Darkly’ and the bombing of North Vietnam in ‘The House That Jack Built’. He flips them around and makes his own sorts of jokes, but they developed out of a genuine concern for civil rights and social issues of the time – in a way that he left behind by the 1970s, when it started to be all about the jokes.

V: He hadn’t decided not to be a novelist yet. If he ever decided that. But he hadn’t even decided not to be a serious writer. He wasn’t completely a humorist, in the ’60s.

G: He was already doing the Hemingway parodies though. ‘This Thing With The Lions’, that was his first one.

V: How many Hemingway parodies are we going to put in the book, by the way?

G: Any fewer than thirty would be unrepresentative. But it might skew things a bit.

V: He must have written a Hemingway parody a year.

G: Let’s have a couple. The book will be full of parodies anyway – Chaucer, Coleridge, Kafka, Conan Doyle, Melville, a lot of Melville – they’re some of the most enduring pieces. They work in an anthology. All jokes need a context, and the context of the parodies is, to some extent, eternal. They’re not dependent on immediate social or political or cultural context. Humorous writing doesn’t last as long as serious – look at Shakespeare’s comedies compared to the tragedies. Or Carry On films compared to … well, almost anything. Lots of Daddy’s pieces are still very funny, but the parodies all are. The passage of time doesn’t do the same damage to a literary pastiche as it does to a joke about the 1964 general election. We need to use the stuff which still works. He was so proud to be compared to James Thurber and S.J. Perelman – but who reads Thurber and Perelman now?

V: That’s all very well, but I see you’ve put two Winnie the Pooh parodies on the list. Do we need two?

G: But which would you remove – ‘The Hell At Pooh Corner’, or ‘The Pooh Also Rises’?

V: Isn’t ‘The Pooh Also Rises’ a double parody of Pooh and Hemingway? We don’t want to make his frame of reference seem limited.

G: But we must include it! That one’s part of a complex triptych of adult/child fictional parodies. Lose ‘The Pooh Also Rises’ and we lose ‘Five Go Off To Elsinore’. We lose ‘The Gollies Karamazov’.

V: Speaking of political relevance, what are we going to do about Idi Amin?

G: Yes. Idi Amin. That was always going to be a problem for so many reasons. The Idi Amin parodies don’t operate in a timeless context like the literary ones. The Idi Amin of now isn’t the one he was writing about. Daddy said himself that he wouldn’t have written those pieces later, once it turned out that Amin was such a monster. In 1974, he just thought he was writing about someone funny.

V: In a funny African voice. That’s the bigger problem. Even if Amin hadn’t turned out to be a monster, those pieces wouldn’t read the same now. ‘Wot a great boom de telegram are!’ ‘Dis international dipperlomacy sho’ payin’ off!’ Monster or not, if you were writing a column about Robert Mugabe, you wouldn’t do him like that.

G: Tempting though it would be.

V: But I don’t want anyone to think he was racist. He wasn’t racist. He went on civil rights marches in America in 1961. And his Idi Amin … he’s not a ‘generic African’, he’s a fully fledged character: childish, megalomaniac, charming, violent, funny. With this comedy voice – ‘Ugandan’ sent up no more squeamishly than if it were Cockney – but people might not read it like that.

G: Maybe we shouldn’t put it in.

V: It would definitely be safer not to. But The Bulletins Of Idi Amin was his best-selling book ever. It sold a million copies. They made a record of it. It made him famous. It’s because of the Amin books that The Sunday Times called him ‘The funniest writer in Britain today.’ Richard Ingrams ran a spoof in Private Eye with Daddy’s picture at the top. Do you remember what that was called? ‘The Bulletins of Yiddy Amin’, of course. They must have cracked open the champagne when they thought of that. Anyway, the point is, those pieces make us nervous and they might give people the wrong impression of him, but I don’t think we can just censor them out.

G: Hang on. Think about Team America, one of the best adult comedy films of modern times; a serious, anarchic, liberal and right-thinking movie. And think of the hilarious pastiche of Kim Jong-Il. He is a very decent parallel with Idi Amin, except even more powerful and even more sinister – and when Trey Parker and Matt Stone make an entire film based on his dictatorship, the centrepiece of it is his hilarious Korean accent. When Jong-Il bursts into tears and sings ‘I’m So Ronery’, it’s pure Alan Coren. People might have been a bit squeamish about Idi Amin in the 1980s and ’90s, but you only have to look at South Park – also created by Parker and Stone – to see that we have come back into a world where everything’s fair game, and exaggerated ethnic mimicry doesn’t make you a racist. I’d hate to think that future generations of South Park viewers would have to watch edited versions, from which Chef has been removed because not all black men sound like Isaac Hayes.

V: Maybe we could put Idi Amin in an appendix?

G: Okay, put those pieces in an appendix, at the end of the 1970s. With a perforated line down the page so people can tear them out if they want, and leave them in the shop.

V: Are we going to put anything in from the Arthur Westerns? I know they were children’s books, but I think I might love them more than anything else he ever wrote.

G: I love them too. Originally Arthur was called Giles. Daddy told me the stories at bedtime and then wrote them down, and it was massively exciting, like my own version of the Alice in Wonderland creation myth.

V: Except without the naughty photographs.

G: But we shouldn’t put them in. The books are brilliant, but they’re for children. If you’re compiling The Essential T.S. Eliot, you don’t include Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats.

V: Okay, no Arthur the Kid. No Luke P. Lazarus, no cricket-playing pigs, no Seminole Gap. So will the book just have the magazine and newspaper pieces?

G: Just? What do you mean ‘just’? He published twenty-six books of them. Collectively, they’re twice the length of Proust. And that’s only the pieces he put in books.

V: But would there be room for something that wasn’t written at all? Extracts from The News Quiz, maybe? He became the twelfth editor of Punch in 1977 and that was the start of his golden age. By the 1980s he had a TV career, he was doing chat shows. Maybe we should include some transcripts of those?

G: And the commentaries from Television Scrabble? His Through the Keyhole work? Look, he was a famous person, he was a sort of celebrity, plenty of people will know him only from Call My Bluff. But that’s not what this book is about. It’s about what will endure of his writing. Let’s just have the writing.

V: I wish he had written a novel. Actually, what I really wish is that he had written an autobiography. He had that great idea for writing one based on all the cars he ever drove … it would have been so good.

G: The 1990s would have been the time for that sort of writing. He left Punch in ’88 and all of that Fleet Street romance – cricket in the corridor, drunken lunches, contributors carving their names in the Punch table, Sheridan Morley, Miles Kington, Basil Boothroyd, Bill Tidy, Bywater, royal visitors – it all came to an end. It had got too businesslike, he was summoned to too many meetings with people who wore grey suits and talked about revenue streams. He edited The Listener for a year and then he came home to write.

V: He wrote the Times column twice a week, and talked a lot about novels and the autobiography without actually doing them.

G: I tried to persuade him. If he was that good at writing sentences, I thought he would write a very good novel. But he didn’t think the two things necessarily went together – he always said that his old pal Jeffrey Archer could write novels but he couldn’t write sentences.

V: I think that was just an excuse. He was never going to get much work done once he came home. Part of the problem was that he had such a happy marriage. He famously never went out for drinks after The News Quiz because he was always in such a hurry to get back home to her and eat veal schnitzel together in front of the TV. Once he was working from home, he got all involved with the domestic routine. He always had an ear cocked for Mummy’s key in the door. He was much happier helping her unload Waitrose bags than sitting at the computer trying to write.

G: And the writing was all about Cricklewood. That strange Cricklewood of his own invention, which didn’t really exist. Except for the domestic frustrations – gas men turning up late, junk mail, plants dying when he went on holiday, tiles falling off the roof, ‘narmean’ – that was all a comic version of his very genuine obsessions.

V: And he did it brilliantly. The American influence, the youthful inspiration he took from civil rights and political stories, disappeared from the writing, and it became a very British sort of comedy – small things, silly things. Herons, hearing aids, hosepipe bans, talking parrots, QPR fans arguing at cheese counters. He was a master of all that.

G: It’s funny to use a word like ‘master’ in the context of a writer whose work was so ostensibly superficial, so entirely motivated by humour. It’s usually the boring ones who get called that. As a writer you want to move people, or at best ‘affect’ them in some way, and for him the easiest way, the only way, was to make them laugh. He got hundreds and hundreds of letters from Times readers, far more, I’m sure, than any of the ‘serious’ writers. They loved him, and they needed to tell him that.

V: I think they loved him because his comedy was so warm, it reflected a charming and optimistic and kindly vision of the world. And it was ambitious, even if it was only a thousand words long, or half an hour on the radio. It’s easy to get a laugh from being nasty or from being philistine, but he didn’t do that. He never hid the fact that he was clever, and he never got a cheap laugh at someone’s expense – if it was at someone’s expense, it was a fair target and cleverly done – but he was always funny, and that’s really hard for Twenty-minutes, never mind a lifetime.

G: I read one obituary of him, a not especially kind one by a man who always bore a grudge, that suggested the old man’s prose did not achieve the rank of ‘greatness’ because he put nothing of himself into his writing – and, at the same time as being annoyed at something negative being said about him, I had to sort of agree with that, at least partly. He was not a seeker after truth in his writing, he was a seeker after laughs. He would also never have dreamed of suggesting he was a major literary figure – the idea would have struck him as laughable. He found the truth a bore, he hated opinions, he distrusted earnestness. His pieces were a flag-wave designed to distract people from the horrors and the tedium of real life and also, in a way, to distract them from looking too closely at him. So you wouldn’t really expect him to lay himself bare in there. But then again, reading all his stuff again for this book, I was struck by how much of himself he was including subconsciously: so much of the humour, for example, derives from a sense of impending domestic disaster: something being spilled, a great mess everywhere, things being lost, maps being misread, planes being missed, pipes freezing, children screaming, people being bitten by dogs … and you and I both know what a stickler for order and tidiness and planning he was – and how all these sorts of little domestic mishaps in fact drove him round the bend so that he wasted a lot of energy worrying about them. But then in his pieces, for forty-odd years, he was making out like he found it all terribly funny. That’s a man’s soul informing his writing if ever anything was.

V: He would have written a great piece about his funeral. It was rich with potential catastrophe – if he’d been there to plan it, the worry would have killed him. But the various strange details all fell into place, and they were perfect. The Cricklewood churchyard that he loved because a ventriloquist is buried there with his puppet. And so is Marie Lloyd – we’ve got his piece about it somewhere in the 1990s section. The rabbi who didn’t mind coming to a churchyard – who advised us, in fact, to ‘drop this prayer, it’s a bit God-heavy’. The cantor who sang a mournful Hebrew song, and then came out to Sandi Toksvig. The moment when Uncle Andrew misread the map, looked in the wrong part of the cemetery and said: ‘We’ve got a disaster on our hands – they’ve forgotten to dig a hole.’ It was like an Alan Coren piece being acted out by accident. And it worked: it reflected everything. The sentimentality about Judaism with its gefilte fish balls and anxious tailors … and the sentimentality about England’s green slopes and church spires … with some lovable, fallible, funny human characters in the middle. If we’d only had an Austin Healy with a copy of Gatsby and a hamburger on the front seat, it would have ticked every box.

G: Speaking of ticking boxes, we still have to write the introduction.

V: We haven’t decided which one of us will type and which will pace …

G: We could just leave it as dialogue.

V: Mightn’t that look a bit lazy?

G: No, no, people will think it was our plan right from the beginning.

V: But then mightn’t it look a bit gimmicky?

G: And thus in some way unsuitable for the introduction to an anthology of writing by Alan Coren …?

V: True, true.

G: Remember the introduction he wrote to that anthology of humour in the ’80s? It looks like a piece of autobiography – except of course it’s all nonsense, not autobiographical at all.

V: And yet at the same time, in a way, it is. Okay, it’s a daft story about a man who dreams of compiling anthologies of Boer operetta lyrics. And who has a preposterous soldier father with a giant tattooed arm. But the basic narrative … a young man who yearns to get into publishing … whose physical, practical, sceptical father thinks he won’t make money from it … the son pressing on regardless, travelling abroad … returning to England at twenty-two, publishing his books and working on a humorous magazine … It is actually Daddy’s mini-life story, but with everything transformed into cartoon, like the farm hands becoming scarecrows in The Wizard Of Oz.

G: Do you think perhaps you’re over-reading it?

V: That was a short story which he thought counted as an ‘introduction’ – but at least he wrote it out in paragraphs.

G: We could call ours a ‘foreword’.

V: Fine. Dialogue it is, and a foreword it shall be.

G: It’s not as if people have forked out Twenty-pounds to read a piece by us anyway, is it? It’s him they want to read.