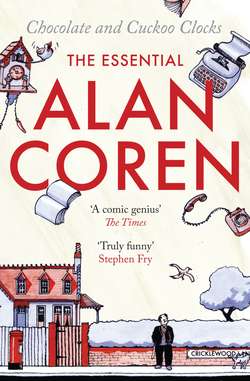

Читать книгу Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks - Alan Coren - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

It Tolls for Thee

Manhattan’s largest fallout shelter, the New York Telephone Company Building rising near the Hudson River, will have 21 storeys without a single window. The vertically striped fortress will house 3,000 workers, who will be capable of surviving a near-miss atomic attack for two weeks.

Life Magazine, November 9th, 1962

For the first few moments, I was convinced that some joker had directed me to the sanctum sanctorum of one of California’s more esoteric sects. The doors sighed shut, sealing me into a huge pastel-coloured hall; on the facing wall was etched the outline of a bell, beneath which stood a long low table flanked by two gently revolving plastic bushes hung with pink, blue, olive and yellow telephones. A row of multicoloured phones, doubtless freshly picked, garnished the table. Behind these sat a motionless young woman, smiling fixedly. In order to approach her, it was necessary to pass between two long rows of identical desks, on each side of which stood a telephone of a different colour, and a rack of pamphlets. No one sat at the desks, and, apart from myself and the votary at the far end of the hall, the place was empty. It is almost impossible to walk down a long aisle towards someone who has been trained to smile. I committed the miserable error of starting my own smile as I began to walk; consequently, by the time I reached the table, I had considerable difficulty in speaking through the grinning death-mask into which my face had been turned.

‘Good morning,’ I gritted. ‘I should like to have a telephone installed in my apartment.’

‘Yes, sir,’ she murmured, softly. ‘If you’ll wait over there by the lavender instrument, I’ll have someone help you with your problem.’

‘I haven’t got a problem,’ I said. ‘I want a phone. Can’t I just leave my name and address with you?’

‘I’m sorry, sir.’ The same monotone coming through the glazed smile. ‘Bell Telephone has found that the most efficient way of dealing with clients’ problems is through the instrument.’

I sat at the desk, looking at the Instrument, wondering whether I ought to smile at it. I heard the girl murmuring on her own telephone. I casually opened one of the bright pamphlets in front of me, and found the familiar catechismal layout prescribed by PR departments of the great industrial organisms. I turned the pages with waiting-room languor, impervious by now to the frenetic hyperbole; after all, I had known before coming here that the net worth of Bell Telephone approximates to that of England, that it is wealthier than the five wealthiest states in the Union, that soon it will have a satellite all to itself, and so on. I was beyond surprise by Bell. And then, on the last page of the pamphlet, I came on this: ‘At present there are more than 85 million phones in the U.S., and by 1975 there will be more than 160 million.’ I went back and re-read it. And realised that the telephone was reproducing at approximately three times the rate of the population of China. This in itself, all other implications aside, had a staggering effect on me. Until then, I had, like almost everyone else, accepted as the two yardsticks by which all other quantities were to be measured, the distance to the Moon, and the population of China. (I have never needed any others, since, at fourteen, I spent two weeks in bed on glucose following a maths master’s attempts to conceptualize infinity for me. We cornered it at one point, and had it belittled to the ignominy of one-over-nothing. I thought about this for a few moments; then I cracked.) Told that: ‘The 1962 model was driven 250,000 miles on two quarts of oil and one tyre-change. This is the distance from here to the Moon’, I am happy. Or that: ‘In 1961, we manufactured one billion ballbearings, or enough to give every man, woman, and child in China two ballbearings each’, I know where I stand. Or knew. Not any longer. Now that small fund of conversation-stopping statistics that I have hoarded for bad moments at parties will have to be completely revised in terms of telephones, lengths of cable, warehouse-loads of dials. I shall have to teach my sons that every fifth child born is destined to become a telephonist. Stuff like that.

The Instrument cut through this morbid reverie. A voice of metallic silk introduced itself, and elicited a file-full of irrelevant personal information before asking, finally:

‘Now, sir, how large is the apartment?’

‘Three rooms,’ I said.

‘So you should be able to get along with only one extension. Is that to be a wall-phone, or a Princess Bedside?’

‘I want one instrument,’ I said. ‘With a long cord.’

A metal snigger.

‘Oh, come, sir! Nobody has long cords any more. Our researchers found that so many accidents were caused by cords getting tangled up with children and pets and things of that nature.’

‘I haven’t got anything of that nature,’ I said.

‘Well, at least you’ll need a Home Interphone. So that you can communicate with the party in the other rooms.’

‘There aren’t any parties. I live alone.’

‘Don’t you ever have guests?’

Of course, since she lived at the end of a lavender cable, the idea that people actually indulged in the gross obscenity of talking face to face could hardly be insisted upon by me.

‘No,’ I said meekly, ‘No guests’.

A pause. I could see the inside of her brain visualising a banner headline: ‘ONE-PHONE RECLUSE FOUND STRANGLED BY ANTIQUE CORD. BODY DISCOVERED AFTER THREE WEEKS BY JANITOR’. I wanted to meet her, I wanted her to see that I was healthy, that there was a spring in my step, that I smiled. But this was impossible.

‘Oh, well,’ said the voice. ‘Of course, you can never tell when a party may drop by.’ I wondered whether she was human enough to be trying to console me. The voice sighed, and went on: ‘Well then, sir, perhaps we can decide on the colour of the Instrument’.

‘Black.’

A tin gasp.

‘Beige, green, grey, yellow, white, pink, blue, turquoise!’ A pause. ‘Nobody has black, sir. We couldn’t guarantee a new Instrument in black. What is the colour-scheme of your room?’

In fact, it’s pale-green. But I knew the consequences of my admitting this. So I joked. I thought.

‘It’s black,’ I said. ‘Black wallpaper, black ceiling, black fitted carpet. Black furniture.’ I waited for her laugh.

‘We-e-ell,’ she said, ‘Why not have a white Instrument to set it off?’

‘All right,’ I said running my tongue over my lips. ‘All right, white.’

‘Wish I could persuade you to have a coloured Instrument. Everyone else does, you know. They’re so much more individual.’

‘Yes. Well, that’s all, I suppose?’

‘But we haven’t decided on the chime yet, have we?’

‘The what?’

‘The chime. You can have a conventional ring if you choose, but for the Discerning we are now able to offer a Gentle, Cheerful Chime Adjustable To Suit Your Activities Or Your Mood.’

‘But how do I know what mood I’ll be in when it chimes?’

‘But on some days, don’t you just long for a Gentle Chime?’

I closed my eyes. For three weeks I have carried on a running fight with my landlord over my request to change my door-chime for a buzzer. And two weeks ago I bought, or, rather, was sold, a Discount House Bargain which keeps perfect time all day, and, having been set for nine a.m., awakes me up at 4.17 by chiming crazily and hurling scalding coffee over the walls and carpet.

‘No, dear,’ I said wearily, ‘I’m something of a strident buzz man myself’.

‘As you choose, sir.’ I could hear her hesitate. I knew she was cracking. Finally she murmured: ‘The Princess Bedside lights up at night.’

‘Quite possibly,’ I said, and replaced the receiver.

After I left the building, I stopped to buy the copy of Life from which I quoted at the beginning of this story. And suddenly I saw her, and her sad sorority, in their last hours, in their windowless concrete pillar above the rubble of New York. Three thousand telephonists, connected only by a web of lavender cable, frantically dialling and re-dialling, while the nightlights flash, and the bells chime gently, over a dead world.