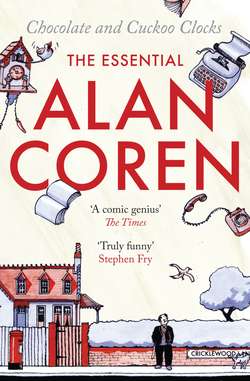

Читать книгу Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks - Alan Coren - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Present Laughter

The introduction to an anthology of modern humour, by Alan Coren (1982)

Nobody who met my old man ever forgot him. The first thing you saw was the sabre scar across his head. The wound had been stitched up by a chanteuse who went in with the first ENSA wave at Salerno, and the only way she could work the needle without passing out was to stay drunk.

His left arm was the size of anyone else’s thigh, and it was tattooed in the shape of a cabriole leg. One of his favourite party pieces was where he went out of the room and came back a couple of minutes later as a Regency card table. People still talk about that. His right arm stopped at the elbow: the rest had been left inside the turret of a Tiger tank after the lid came down, somewhere in the Ardennes Forest.

When he came back from the War, he just laughed about it, at first. But then, one night in the winter of 1945, he suddenly said:

‘You’re going to have to help me at the brewery, son.’

I said: ‘I’m only seven, Dad.’

It was the first and only time my old man hit me. If he had hit me with the left, I should not be here now; but it was the right he threw, and being short it had neither the range nor the trajectory, but it hurt just the same when the elbow connected.

Later on, he quietened down and asked me what I intended to do with my life if I didn’t want to hump barrels.

‘I want to do anthologies, Dad,’ I said.

He looked at me hard, with his good eye; the other one is still rolling around near El Alamein, for all I know.

‘What kind of job is that for a man?’ he said.

‘I don’t think I’m cut out for humping barrels, Dad,’ I said.

He spread his arms wide; or, more accurately, one wide, one narrow.

‘It doesn’t have to be barrels. There’ll be other wars, you could go and leave limbs about.’

I nodded.

‘I thought about that, Dad. I could be a war anthologiser. A war provides wonderful opportunities, collected verses, collected letters, collected journalism, things called A Soldier’s Garland with little bits of Shakespeare in. Did you know that Rupert Brooke’s “The Soldier” has appeared in no less than one hundred and thirty-eight anthologies, Dad, nearly as often as James Thurber’s “The Secret Life Of Walter Mitty”?’

He thought about this for a while.

‘Is there money in it?’ he said at last.

‘Dear old Dad!’ I said. ‘An anthologiser doesn’t think about money. He is pursued by a dream. He dreams of making a major contribution to gumming things together. He dreams of becoming a great literary figure like Palgrave or Quiller-Couch.’

‘And how do you go about learning to anthologise, son?’

I smiled, but tolerantly.

‘You can’t learn it, Dad. It comes from the heart and the soul. Fifty-pounds would help.’

People have asked me, three decades on, in colour supplements, on chat shows, what the major influence on my work has been. I tell them that it wasn’t Frank Muir, it wasn’t Philip Larkin, it wasn’t even Nigel Rees or Gyles Brandreth, important though these have undeniably been: it was the day my old man took his last Fifty-pounds out of his wooden leg, and set me on my path.

I left school soon after that. There was nothing they could teach me that would not be better learned in the real world: the experience of felt life is what lies at the still centre of all the great anthologies. I shipped aboard a coaler on the Maracaibo rum, and I discovered what a Laskar likes to read in the still watches of the equatorial night. My first anthology, a slim volume and privately circulated, consisted of buttocks snipped from Health and Efficiency interlarded with Gujurati limericks and reliable Portsmouth telephone numbers. Juvenilia, perhaps, and afflicted with the sort of critical introduction that I have long since learned always goes unread, but no worse than, say, the annual Bedside Guardian.

Two years later, I jumped ship at Dakar, and took up with a Senegalese novelty dancer who had a tin-roofed shack down by the harbour and a brother who worked three days a week as a roach exterminator in the British Council Library. It was perhaps the most idyllic and fruitful period of my life: it was mornings of grilled breadfruit and novelty dancing on the roof overlooking the incredible azure of the Indian Ocean, and afternoons of studying the anthologies her brother would steal from the library, the absence of which, when noticed, he would attribute to the kao-kao beetle which subsisted, he said, entirely upon half-morocco.

I read everything, voraciously: I learned how anthologies worked. I divined the trick of bibliographical attribution whereby the skilled anthologiser credited the original source, rather than the previous anthology from which he himself had worked. I noticed how an expensive thin volume could be turned into a cheap fat volume by amplifying it with long sections of junk that happened to be out of copyright. I made out an invaluable list of titled paupers who could be called upon to endorse the anthologiser’s choice with tiny masterpieces of prefatorial cliché, usually beginning: ‘Here, indeed, are infinite riches in a little room,’ and ending with a holograph signature.

The idyll could not last: there was a waterfront bar where expatriate anthologisers – they called themselves that, though few among them had ever collated anything more remarkable than privately printed regimental drinking songs, or limited-circulation pamphlets called things like The Best of the Old Eastbournian, 1932–1938 – gathered of an evening to drink and argue recondite theories of anthological technique, and one night I had the misfortune to fall foul of a gigantic ex-Harvard quarterback who claimed to be on the point of closing a two-figure deal for his Treasury of Mormon Prose.

I shall not distress you with the details. When I woke up the following morning, my youthful good looks were gone, to be rapidly followed by my Senegalese paramour. Two weeks later, I left the infirmary and returned, far older than my twenty-two years, to England.

Britain, in 1960, was not at all as it had been a few scant years before. A new spirit was abroad, a harsher, grittier, more realistic spirit. It was the Age of Anger, and the whole face of English anthology had changed overnight.

Gone were the elegantly produced collections of ethereal lyrics and robust nineteenth-century narrative verse. Gone were the leatherbound volumes of India paper bearing the jewelled fragments of English prose from A Treatise on the Astrolabe to Hillaire Belloc on mowing.

In their place, the new race of angry young anthologisers was churning out paperback collections of bogus radicalese entitled Whither Commitment? and Exercises In Existentialism and The Right to Know – Essays on the Obligations of Communicators in a Negative Environment. As for the more popular market, such classics as A Knapsackery of Chuckles or A Wordsmith’s Bouquet had been thrown out in favour of The Wit and Wisdom of MacDonald Hobley and Dora Gaitskell’s Rugger Favourites.

Ninety per cent of all anthological output was manufactured by the BBC, linked on the one hand to a vaguely similar broadcast, and on the other to a wide range of dangle-dollies and jocular tea-towels.

These were, in consequence, bleak years for me. My entire creative life to this point had been wasted, the art of anthology to which I had dedicated myself was no more. Not that I surrendered lightly: by day, I worked as stevedore, cocktail waiter, pump attendant, steeplejack, male model, by night I pursued my muse, working feverishly and without sleep to produce, in the space of five years, The Connoisseur’s Book of Business Poetry, The Big Book of Boer Operetta, A Nosegay of Actuarial Prose, and, perhaps my own favourite, We Called It Medicine: A Selection of Middlesex Hospital Correspondence Between the Wars.

I was thrown out of every publishers in London. It was the same story everywhere, as the 1960s rolled inexorably on and television worked its equally inexorable way deeper and deeper into the culture – I was not a Face. For a new breed of anthologiser was abroad: the personality. Names like Michael Barrett, Jimmy Young, Robert and Sheridan Morley, David Frost, Antonia Fraser, Freddie Trueman, Des O’Connor, Henry Cooper and the rest, all represented the New School of English Anthology; they were household words who held the publishing world in enviable thrall.

It was upon this inescapable realisation that I finally threw in the creative sponge. I had reached that nadir which all anthologisers have at some time or another plumbed, when you feel you can never skim through a book again. Worse, my run of bearable jobs had come to an end with the installation of an automatic car-wash, and I had nowhere to turn but to a weekly humorous magazine, where I was employed to manufacture lengths of material which could be inserted in between pages of advertising in order to display them to advantage. It was, as can readily, I think, be imagined, lonely, grim and unrewarding work, relieved only by my access to a comprehensive library of published humour and the constant stream of new humorous books which paused briefly in the office of the Literary Editor before being wheeled around the corner to a Fleet Street bookseller prepared to exchange them for folding money.

I thus came to read every comic word that had ever been written. It has left me grey before my time, and I jump at the slightest sound, but it has produced one strange by-product, an effect unsettling yet at the same time curiously thrilling: when I had been convinced for the better part of two decades that every creative instinct within me had shrivelled and died back like a frostbitten rose, a glimmer of the immortal longings of my youth returned. On a chill November evening, as I huddled for warmth among the teetering piles of comedy, a tiny spark of – shall we call it – inspiration no bigger than a dog-end falling through the night flashed deep within my head and, a second later, hope blew upon it, and it glowed.

This book, then, is the result. Whether, given my time again, it would have been wiser to have spent the thirty years in humping barrels, I cannot say. I know only that it would have been a lot easier.