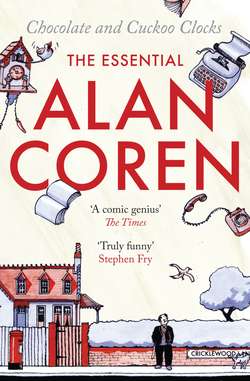

Читать книгу Chocolate and Cuckoo Clocks - Alan Coren - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMELVYN BRAGG

Introduction

When I first met Alan, he was heading for the library in the back quad at Wadham College. He was also headed, the word was, for a brilliant academic career. I still have no idea why he stopped to chat with a callow newcomer from the sticks, but I remember vividly the blast of bonhomie, the instant embrace into an unearned familiarity which turned to friendship, and the dazzle of his wit. This was Oxford on stilts.

I was quite alert to accents at the time, but Alan made it quite difficult. He had the breezy metropolitan machine gun manner, but it was already minced into a sort of Oxford ease. Not Upper but no longer WC or even LMC.

He had adopted the linguistic camouflage as immediately as he had put on the correct 1950s tweed jacket, and maybe even cavalry twills, and God help us perhaps a cravat.

Had he re-launched himself as gentleman Pip? Yes. But that was job done. Over the next decades of Punch lunches and the occasional posh dinners, he rested cheerfully in the berth he had made for himself so characteristically quickly, and the machine gun delivery never slowed down.

He carried his literary gifts into the columns and programmes which seduced him from scholarship, but scholarship blazes through his earliest pieces in the 1960s.

In ‘Under the Influence of Literature’, for instance, he describes an awakening. One morning aged thirteen and three-quarters, he wrote to his mother: ‘Please do not be alarmed but I have turned into a big black bug.’ He had read Kafka, was ‘in that miserable No-Man’s-Land between Meccano and Sex’, and was about to change heroes from Captain Marvel and Zonk to Raskolnikov and Werther.

In another early piece in the same period, in a single paragraph mocking the failure of the English to produce plausible Bohemians, he mentions more than Twenty-authors: ‘Our seed beds have never teemed with Rimbauds and Kafkas and D’Annunzios … Our Bohemia is populated by civil servants, Chaucer and Spenser and Milton … by corpulent family men Thackeray and Dickens and Trollope …’

He then launches into the excesses which were to colour some of his best comic writing. ‘Cowper mad among his rabbits, Swinburne, a tiny, fetishistic gnome as far from Leopold von Sacher-Masoch as water is from blood …’

Then he turns his guns on Wordsworth. I ducked.

It would have taken at least three years to write that up as a thesis, and another five to produce it as an academic masterwork, but an extraordinary speed of thought was Alan’s great gift; the necessary tortoise pace of serious research would have driven him screaming mad. And he was blessed with what was almost a disease of humour. These two qualities gave him his take on the world.

Later, he begins to wean himself from the literary inheritance he conquered and subsumed so thoroughly. His 1970s pieces take off from a standing start, which can be seen in ‘Let Us Now Phone Famous Men’: Mao Tse-Tung, Kosygin, the Pope, full of Coren fantasy and phonetically convincing accents. Then there’s a little masterpiece on alcohol and the artists which begins: ‘“Shrunk to half its proper size, leathery in consistency and greenish-blue in colour, with bean-sized nodules on its surface.” Yes, readers, I am of course describing Ludwig van Beethoven’s liver.’

As ever, he takes it for granted that his readers are as culturally clued up as he is, and the jokes work the better for that.

I think that what was tugging away at Alan in the 1960s was not so much academic regrets as fictional possibilities. He wanted to write novels. Perhaps he did, and didn’t publish them. He was certainly sufficiently talented, inventive and energetic.

The only reason he didn’t, that I can think of, is that he came to prefer the columns and the radio, which themselves became short fictions, unceasing figments of his imagination.

As a friend and someone to talk to (or more usually listen to), it never took him more than a few minutes to torpedo even the most serious conversation with wit meant to sink it.

He was one of the very few people who made me laugh out loud. He does still.

For which, old pal, much thanks.