Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 2

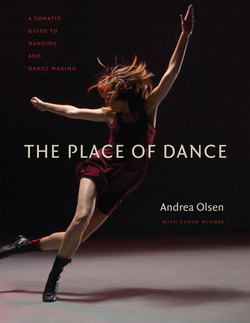

Grupo Corpo

Benguelê

Photograph © José Luiz Pederneiras

Attitudes

What We Bring with Us

I can’t believe how long we go without dancing; I mean days, minutes, hours….

—Janet Adler, interview

People have complex views about the dancing body: it is respected and ignored, craved and forbidden, celebrated and scorned. Historically, dance has been feared and banned by both governments and religions. It challenges convention, threatening the status quo.1 Who knows what will happen when the body speaks? In the media, dancing is harnessed to sexuality, co-opted by commercialism, and dressed up by fashion. Is that why we are so afraid of dancing?

Body schema is one term neuroscientists use for overlapping maps in the brain that make a person aware of what his or her body is doing. Body schema is fed by sensory nerves throughout the body that tell us about our selves in relation to the world. Body image, in contrast, describes the constructed representation developed through life stories and attitudes accumulated from birth. Body schema and body image may not match—what your body actually feels and looks like and how you imagine you look may be worlds apart. This is what science writers Sandra Blakeslee and Matthew Blakeslee describe as “dueling body maps.”2

But perception is a construct, and attitudes change. It can be useful to take a look at familiar views and values, and discern how those ideas were formed. Patterns that you established at age twelve, eighteen, or even last week may no longer be appropriate for who you are now. Conditioned habits in coordination can result in overcontraction of muscles (think tight hips). Mental seeds about the dancing body manifest in action. We choose what to plant and what to nourish. This requires uncoupling biography and biology—personal story and genetically endowed structure. Receiving sensory signals, updating interpretation, and allowing communicative expression changes us. The ways we construct meaning are impacted: our view of the world and what we think is real.

We rebuild perception daily, moment by moment. Because dance is both a visual and a kinesthetic art form, dancers learn to see-feel movement. Hence the relevance of eyes-closed and skin-focused somatic work to feed and enhance the sensory maps, along with “outside eyes” offered by teachers, mirrors, cameras, and—eventually—audiences to corroborate sensation. The opportunity to perform various roles requiring new connections—beyond typecasting—enhances neurological plasticity. Working with diverse teachers, choreographers, and dancers keeps the body image responsive, refreshing sometimes-compromised sensory maps.

Pre-movement is the readiness state in the body at any moment, and it determines outcome of actions.3 Attitudes toward ease or distress continually create the conditions in which movement unfolds. At the instinctual level, survival is everything. Conditioned pathways in the body fire before conscious movements occur based on past experience. What is threatening or stressful to one person—performing, for example—may create safety or delight in another. In this way, our attitudes continuously orchestrate our actions.

Dancing is for life. It’s potent at every stage, and different at every age. As you deepen and grow through life experience, the edge of investigation shifts. This freshness of challenge supports lifelong involvement with no preknown sequence. There is a part of the self that remains ageless and a part that reflects growing maturity in relation to the vastness of the art form. Age is only one factor. Deep experience at any age—traumatic or joyful—rearranges how life unfolds.

Dancing and art making are natural doorways to self-discovery. For those who love their bodies, the passion and drive of movement might come without resistance. Yet, dancing requires wholeness—growing all parts of the self. If we stay purely at the physical level, over time the body gets hard and dull. Opening to unknown realms deepens and enlivens creative work. And for those who have a difficult relationship with body—emotional or physical challenges, overload or lack of weight, or a stubbornly intuitive or intellectual nature that would rather not be bothered with focusing on body—dance, if allowed, will unfold new dimensions.

What happens to our body attitudes as we consider ourselves dancers? Filtering daily life through an intelligent, informed physicality takes us beyond the ego, fame, or commercialism of dancing. In this way, everything we read or do has relevance to living a creative life: the clothes that move with our bodies, the light on our skin, and the words on this page. We may be doctors, therapists, parents, pastry chefs, organic farmers, teachers, or CEOS of thriving companies, but our embodied dancer-selves are alive and well—even if we never put a foot onstage. Life, in essence, is our ground.

STORIES

Do You Dance?

When I travel, I ask people about dance. Taxi drivers are particularly insightful. In Seattle, one asks where I am going. To South Korea, I respond, to give a lecture and dance. “I’m a dancer too,” he says, “from the former Soviet Union. I’ll show you some moves.” At the airport, he sets my bag on the curb and begins a short routine, with fancy footwork, quick turns, and polyrhythmic arm movements. Noting my delighted look, he adds, “You’ll do fine. You’re a professional.”

≈

In the cloud forest in Mindo, Ecuador, our young bird guide Javier says, “All men dance in Ecuador. If you don’t know how to lead, you’ll never get a girlfriend.” Our Galápagos guide, Washington, hosts a top-deck dance party for our small group of academics. Trying to inspire our salsa flow, he partners us one by one. Downstairs the boatmen are dancing. When the music stops, they are tying ropes and cooking dinner—living dancing.

≈

The passport inspector in London asks, “What’s your profession?” Dancers often get a suspicious look, so I try “Professor of dance.”

“That’s fantastic,” he responds. “I do ballroom. If we all danced, the world might be a better place.”

Looking Upward

After a week of “bonding with gravity” in a workshop on perception with Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen at Earthdance, she takes us outside. “Now, bond with heaven,” she instructs. Energy rises up, from the roots of the soil toward the sky. At first it feels too light and joyous. Then it’s inspiring. Levity partners gravity.

TRACING YOUR FEET

With colored markers or chalk and a sheet of blank paper large enough for your feet:

• Trace around the outside of each foot.

• Fill in the drawing, taking time to color any sensations, images, ideas, injuries, memories, and associations.

What’s Important?

An aikido sensei declares that a fight is over before you begin. It’s the preset tone in the body that determines what happens. Coordination is set by your attitudes; the actual movements are too late.4

There’s Time

Ending a workshop at the Seattle Festival of Dance Improvisation (SFDI), we sit in a large circle to share feedback. “I’m glad the three presenters are old,” one young participant says. “In your twenties you think you have to discover and understand everything immediately. But these folks are still dancing in their fifties and sixties. There’s plenty of time.”

Finding Your Feet

Teaching at the Nobel Peace Prize Forum with Dr. Wangari Maathai at Luther College in 2006, one learns to stand tall. A Nobel laureate from Kenya who planted over 30 million trees in Africa with women’s groups and her Green Belt Movement, Dr. Maathai helped rehabilitate the land and revise power structures. When we meet, I hear that she is third on a “hit list” to be assassinated in her homeland, yet she radiates positive energy and maintains a resonant voice. At lunch I ask, “How do you sustain energy for lecturing and travel amid threats?”

“I exercise every morning,” she says, “no matter where I am or what is happening—to balance the stress.” After her keynote address, she arrives at my movement workshop, lies down on the floor, and closes her eyes. With cut and cracked feet that know and trust the Earth, she is at home in her body.

WHY DANCE?

Fifteen statements from the first week of a choreography class

To learn about a place.

To communicate without words.

To have an open, honest chest.

To fall in love with the original ways the body can move.

To have the freedom to interpret dance in my own way.

To succeed through the body.

To give of myself.

To match swiftness with strength and to discipline both forces.

To feel humanity.

To find myself alive in my body.

To experience an essential lightness, joy, or relief.

To tap into a source of energy.

To gain confidence in my own movement.

To say, “Here I am, world.”

To feel a natural progression toward change and internal insight.

Tracing your feet

Illustration by Caryn McHose

TO DO

Finding Your Calcaneus (Caryn McHose)

15 minutes

Feet connect you to the Earth. Stability or instability in your base both reflects attitudes and affects whole-body coordination.

Seated, feel for your heel bone—your calcaneus.

• Trace its contours. It’s large—hold it in your hand.

• Notice that it travels from back to front in your body, ending in front of your ankle joint and extending behind.

• Use one hand to circle your calcaneus, and notice how the rest of your foot and toes are directed by the heel.

With a partner, Partner A seated on the floor, Partner B standing:

• Partner A, hold the right calcaneus of Partner B, rooting it to the floor.

• Partner B, take time to feel the weight of your heel bone, amplified by your partner. Imagine a vector extending back from your heel bone, anchoring you in space.

• Partner B, take a walk, feeling your heel bone as you walk.

• Trade roles; do both feet.

Foot x-ray showing calcaneus

Image by Alena Giesche

TO DANCE

Opposite-Voice Dancing

15 minutes

Exploring attitudes, you both value your personal voice and seek range—new horizons. Sometimes it takes a bit of prodding to get out of deeply set habits. As you explore your opposite-voice dance, familiar movements don’t go away; you just find more choices.

• Improvise an opposite-voice dance. Start with the qualities you didn’t include in your familiar-voice dance (Day 1). Allow awkward feelings as you explore; push into unfamiliar use of time, space, and pacing. If your other dance was lyrical, make this angular. If you like to go fast, now go slowly. If you are always edgy, try the opposite.

• Borrow; imitate vocabulary that’s “not like you.”

• Dance long enough to fully inhabit this physical embodiment/exploration; push your limits of concentration and endurance.

• If working in a group, dance your opposite-voice dance, witnessed by others.

• Explore improvising this voice in different places—for example, the studio, outdoors, and in your kitchen. Does place change how you move, how you perceive yourself?

TO WRITE

Why Dance?

20 minutes

Why do you dance? Begin articulating your views; make a list without hesitating.

David Dorfman Dance

Disavowal

Photograph © Vincent Scarano

STUDIO NOTES

DAVID DORFMAN teaches a technique class at the American Dance Festival at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (2005). Consider David’s words as an abstract sound score with some literal handles; there’s not necessarily a linear logic:

Think of this as a dancing class rather than a “dance class.” A dancing class is not limited to style.

Walking: Let the torso initiate weight change; let it curve to the side.

• Think of the comingling of circles and lines in your body and in space—let your movement be inspired by circles in the ribs, circles in the pelvis.

• Think of movement as more air conscious, feeling constructive resistance in the air, texture in the air, and then go to the fullest extent before you go on to the ground—soft, into the ground.

• Then imagine where that leads you.

• Be pleasantly demanding of yourself.

• Start a phrase low to the ground, with momentum—deep hip flexions, with turns, with head throws perhaps, with a head dive and then the leg up and around in a giant circle.

• Breathe through your limbs.

• Nothing is flat; everything has contour.

• Accentuate your breath.

• Feel weight in the two halves of the pelvis; let them be independent.

• Reach energy out through the toes and fingertips. Think of reaching both sides of the room at once.

• Go against your preferences, your predilections: absorb new kinesthetic patterns. Do it like an adagio (while you are learning), and it will sink in.

• Roll on your back, feel your legs dropping into the pelvis, recycling up through the head.

• Take a deep breath in and exhale audibly.

• Let the legs release. Maintain that looseness as you’re dancing.

• Try to do something new. Feed in something new.

• See the big picture—the room, the other dancers, and the light.

• Remember initiation and articulation—details.

• Explore different movement qualities, so you’ll be ready to use them.

• Be sure to keep the reputation of modern dance as a serious art form! (I’m joking!)

• Greet your colleagues, talk, and laugh. Keep moving as you chat and check in. Include this energy (human interaction) in your movement.

• Circular movement, linear movement, smart feet, big picture.

• Add weight bearing on different parts of the body.

• From your newly discovered place on the ground, as you continue to move toward standing, test out an aversion toward vertical; explore off-balance, curvilinear space.

• Go with, in, and around the music/the silence.

• Look at each other; have fun now; relax.

• Pause. Close your eyes and relive the last minutes in your mind’s eye. “Yes, that was you.”

• See yourself doing three moves you’ve never, never, never ever done before.

• Open your eyes. Take a walk around the room. Let the pelvis use all its curvaceousness.

• Knees are easy. Top of the head floating up toward the ceiling.

• Feel the diagonals in the space.

• You are supported by the architecture, by the air, by your pals.