Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 4

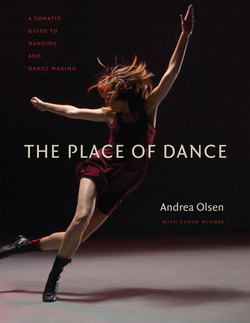

Bandaloop

Artistic Director: Amelia Rudolph Dolomite Mountains of Italy

Photograph © Atossa Soltani (2006)

Fire

What We Might Need

Looking for that place of magical intensity …

—Barry Lopez, lecture

Sometimes we need fire: heat, will, the drive that gets us up in the morning and out to the studio, classroom, or world. Fire is passion, essential in the process of overcoming inertia, motivating curiosity, and committing to action. Fire excites us to begin a project—striking the match. But fire also sustains—the slow burn. How do we find our passionate nature and feed expression without exhausting ourselves, hurting others, or damaging the Earth?

Fire is energy. Ninety-nine percent of all energy on Earth comes from the sun. Heat from this radiant source is stored in plants and integrated into our bodies through the food we eat. Absorbed in the digestive tract, nutrients fire the mitochondria of our cells, and fuel our lives. Sustainable energy of body, like sustainable energy of Earth, involves choice making. Energy is energy; we do with it what we will. The same energy we use to rage at a friend or disparage an enemy could build a school or make a dance—it’s all fire. We have choice about how we channel the energy that moves through us.

Many dance-training techniques are focused around fire; aspects of each dance form evoke it. Inner fire needs healthy pathways for expression. While dancing, we can notice when we build energy and when we let it dissipate. Some physical practices and rehearsals feel good at the moment, but over time they burn us out. Others aren’t energetic enough, leaving us in a vulnerable state of sensing without directed action. Getting to know qualitative range in movement—from tiny flame to full burn, cool-down, coals, and afterglow—is essential.

Investigating the substance of personal fire—its history and range—brings perspective. Unresolved anger or addiction to an endorphin high is not enough to sustain a dancing life. Valuing dimensionality lets us play. Every body system has aspects of the fire element. Discerning the alchemy that’s right for the day, we know when an energetic practice serves and when it’s counterproductive. Some days, less can be more. And fire is contagious. As we access healthy drive in our dancing, we can encourage others to meet their potential.

The fire body has many dimensions, including the volume body and the agency body.1 The volume body is our visceral self. This core is the living, breathing organs that animate emotions and expression. The volume body orients us to others and to place. This is our warmth: our breath, heart, guts, and sexuality. What does the volume or visceral body need to be supported in expression and regulated in appropriate action? Sometimes we meet resistance at the level of the organs. If there’s a protest going on, there’s an intelligence getting expressed. Don’t be limited by self-judgment. Acknowledge resistance; when that gets met and re-sourced, energy courses forth naturally—because it’s inherent.

The agency body is our skeletal, muscular self, directing the volume body through space with an axis. Bones propel the body in contact with an outer surface—in most cases, the ground. Where we initiate movement at the bone level clarifies action and reveals intention. For example, moving from the hip joint rather than the knee creates a distinct look, trajectory in space, and whole-body coordination. As we differentiate the skeletal parts, we find a new level of integration. There are 206 bones in our highly mobile human skeleton; each has weight and takes up space. Skeletal directionality supports agency, our capacity for action in the world.

Muscles move the bones, building heat. If we need more fire through the agency body in our dancing, we can increase muscularity. Muscles, however, require responsive tone so they can move quickly and efficiently as well as powerfully. Sometimes willfulness creates rigidity in the body: we become irritable or entrenched in patterns. Ideally, we have toned, responsive muscles throughout, without hierarchies or favorites. Heat creates sweat, released through the living, breathing membrane of skin. The measurable electromagnetic field around the body is also heat; we feel it when we move with partners. Muscles play a role in invigorating our lives, moving beyond inertia into action and interaction.

Air modulates fire. With each breath, the outer environment becomes inner, and what’s inner becomes outer in cyclic exchange. Breath is an effective partner both in activating heat in the body and relaxing our drive. Breath rate and volume affect responses throughout the body. Short, quick breath arouses alertness in the nervous system; slow, continuous breathing calms the body-mind. Oxygen levels in the blood cue ease or stress. We have choice how we breathe, impacting movement expressivity.

Fire has a role in protecting what we love, standing up for values. We need to know that we can speak, act, and respond effectively in challenging encounters. Then silence and focused stillness are sourced in knowledge of the fire body—in fullness—not in repression. As we practice accessing our passion and channeling it in life-enhancing ways, we activate heat without unnecessary burn.

STORIES

Audacity

Visiting the Parthenon with Greek archaeologist and dancer Sophia Diamantopoulou, we step into an area cordoned off from tourists. Climbing worn steps, we pause in the heart of Athena’s temple. Once the religious center of Athens (a symbol of Athenian supremacy for their allies, and a reminder of the political power and glory of the city), the temple was forbidden to all but priests—no women. Continuing on to the outer columns, we note where Isadora Duncan was famously photographed, and take turns inhabiting her poses.

In the early 1900s, discarding breath-restricting corsets for flowing Greek tunics, Isadora claimed ancient Greece as her source and changed the course of Western theater dance. In her book My Life, she describes filling her solar plexus “with vibrating light … not the brain’s mirror, but the soul’s.”

Driving across Athens to the area of Vyronas, we arrive at the Isadora and Raymond Duncan Dance Research Center. Situated on the top of Kopanos or Avra Hill, it has an unobstructed view of the Acropolis. It was here in 1903 that Isadora and her brother Raymond built their first school—facing off with the gods, goddesses, and political and religious powers of ancient times. One hundred years later, graffiti covers outdoor walls of the garden courtyard, and the big wooden entrance is locked. I pound on a door, and a dancer emerges. Young artists are inside, still creating.

BONE MARROW

Bone marrow is the site of all blood production, including red cells, white cells, and the platelets that transport oxygen. Bone marrow connects us to blood-full, oxygen-rich, passionate movement. Bones are as strong as granite and also as fluid as the lava that created it. In dancing, focusing on the hard, outer layers of bone gives grounding and directionality; as we focus on the marrow within, the experience of bone heats up. One way to focus like this is to imagine breath traveling directly to the core of bones, bringing oxygen needed to create more blood. 2

The Ride

It’s predawn in Bali and heat already surrounds us. We are headed to the top of an ancient volcano to greet the sunrise overlooking the caldera, then bicycle from top to base. Speed is part of the ride, yielding to downward pull or putting on the brakes at the edge of safety. Moments of free fall bring childhood glee: the independence of bike and body as one. We pedal more slowly through farmlands and villages to catch our breath, experiencing the contours of this land. As muscularity mixes with unfamiliar terrain, inner heat meets outer heat on this three-hour ride. Exhilaration comes from exertion.

Finding Direction

Dancer Cat Miller spins out movement; her body loves to dance. But when she is asked to give form through choreography, it’s a laborious process. Moving from visceral, gutsy dancing to linear, directed action with a beginning, middle, and end requires a shift of focus. In her senior project, she finds directionality through emotional connection: once she has the framework of story, the abstraction of movement takes form. Her dance isn’t literal, but she illuminates a passionate world she can inhabit as a soloist, allowing the audience to accompany her on the journey.

Feet to the Fire

Wesleyan University sponsors a Feet to the Fire project, partnering choreographer Ann Carlson with environmental educator Barry Chernoff. The first two goals stated in the project’s description are “to address the need for a deeper understanding of issues surrounding global climate change through multiple lenses; and to use art as a catalyst for innovative thinking, scientific exploration, and student engagement.” Culminating the exploration is a site-specific dance project in which students learn “to question the boundaries of the certainty of knowledge and learn how to act when there are no right answers.” Embodying the time-sensitive dialogue around a warming planet can produce despair. Instead, this project cultivates participants’ passions and response. There is opportunity for hope.

Across the Expanse

Teaching in Italy, we head to the National Dance Academy of Rome, where our dancer-guide Susanna was once a student. En route we visit the Colosseum and meander through the Roman Forum. Once the political and social center of an empire, the temples are nestled between two of the seven hills of Rome. We note the flame where Caesar was murdered, then make our way across a river of traffic and up the adjacent Aventino Hill.

Amid dancers scurrying to classes, we find a photo exhibit of the academy’s founder, Jia Ruskaja. This Ukrainian dancer, inspired by Isadora’s work, created her own academy in 1940 with gardens, studios, and indoor-outdoor stages. Pictures depict dance history through the life of one woman and her school, all the way to the present.

We see her dancing in nature (like Isadora), with “Oriental” costume (like Ruth St. Denis), in deep contractions (like Martha Graham), and in music choirs (like Doris Humphrey and Rudolf Laban). Newer photos show contemporary artists such as Pina Bausch performing at the school.

Departing, Susanna points at a keyhole in a wall; peering through, we see Saint Peter’s dome in the Vatican framed across the expanse. Jia Ruskaja, in the lineage of Isadora, built her dance legacy facing the powers of the time and made a lasting impact: audacity in action.

Caryn McHose, vessel breath

Photograph © Kevin Frank

TO DO

Vessel Breath (Caryn McHose)

15 minutes

The vessel breath invites reconnection to the core of your being. The gut body has particular significance for dancers in a culture that encourages habitual overcontraction of the abdominal wall and restrictive flatness of body image. Here’s a way to begin to reconnect to the natural organic place of nurturance and aliveness in the body.

Find a comfortable position, seated, eyes closed. In the theater of your imagination, envision a primitive (hollow) sea squirt or sea anemone attached to the ocean floor:

• Focus your attention on your mouth. Start by yawning, stretching the mouth and back of the throat.

• Appreciate the hollow volume of the mouth and throat cavity.

• Invite an easeful and audible inhalation and exhalation.

• Continue to relax the gut tube.

• Allow the dilation of this volume within your body.

• Continue to breathe, allowing any sound to emerge—like an ocean breath.

• Create and inhabit space inside, like shaping an empty vessel (a vase), with a pelvis base.

• Envision yourself as all gut—a vessel empty or full. Nourishment flows in, flows out; there’s nothing to do. Can you be present there?

• Continue this breath for some time, following impulses for movement as they come.

• Be gentle and know that this is a lifetime journey.

This is related to ujjayi, a breath in yoga in which you slightly activate the vocal folds and surrounding tissues (glottis) deep in the throat to heighten sensation.

Skeleton

Photograph © Susan Lirakis

TO DANCE

Dancing through the Body Systems (based on the teachings of Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen)

30 minutes

When you move through the bones, organs, and muscles, you access heat and enhance the life force in your body.

Dancing from the Bones (clarity and directionality)

Begin moving, with attention on your bones.

• Bone weight: explore how your bones create momentum in movement. Drop an arm, leg, or head in an arc and follow its trajectory in space. (This is pendular movement.)

• Bone directionality: explore how your bones lever you off the floor and propel and carry you. Extend a limb and follow its vector or line of intention.

• Bone contour and architecture: consider the curves, holes, and arches. Circle your pelvis or ribs, follow their circumference, and trace their inner archways. Sculpt space.

• Investigate head-to-tail movement, the central axis of the body. Remember life as a fish, undulating side to side. Consider how we carry wave motion through our spine in human form.

• Bring your focus to the marrow—the generative core of bones. This is where all the blood in your body is produced. Imagine breath flowing into the marrow, life flowing out.2

• Dance from your (206) bones; dance from the marrow, exploring the fire of each.

Dancing from Muscle (heat and qualitative range)

Start in movement (muscles move the bones). Explore:

• Pumping, pulsating, sponging (contracting and releasing) the muscles. Focus not at the joints, but between the joints.

• Energy level in your movement, raising the volume on speed and effort.

• Range from tiniest to grandest movement, and back.

• Endurance and repetition. Go beyond your personal 100 to 110 percent; reverse to quietest, slowest, least effort.

• Resistance, using more muscle than you need to do an action. Contract one muscle against another for sustained movement. Activate, motivate by lowering your body toward and away from the floor to increase resistance with control, getting longer and stronger in your muscles.

• Spatial integrity, linking throughout the 600 muscles in your body as one muscle system. Muscles work in groups, and are interdependent. Lift your arm, and your calf muscle fires to stabilize your base. Feel connected!

• Keep moving, building and noticing heat, sweat, drive.

Dancing from the Organs (weight and volume)

Stand, with your hands on your belly.

• Pour your belly weight forward into your hands. Allow the organs to release toward gravity, and catch them in your hands. Jiggle the organs, feeling their weight, volume, and tone (through the layers of abdominal muscles).

• Come back to vertical plumb line and yield the organs back toward your front spine. Plump them out. (We sacrifice so much for flatness.) Support with the abdominal sheath, while keeping spacious through your organs.

• Move with awareness of your lungs: the lungs empty and fill.

• Move with awareness of your heart: the heart is a cardiac muscle condensing and expanding; it has both weight and density.

• Move with awareness of your digestive tract: it connects mouth through anus in one long tube, with various structures to break down and absorb nutrients. Initiate movement with your stomach (left side; it fills and empties) and liver (right side; it’s dense, filtering blood). Your breathing diaphragm is the ceiling for your liver and stomach, massaging.

• Explore the twenty-one feet of small intestine, nestled in the frame of the pelvis: asymmetrical, gutsy, undulating, pulsing, expressing.

• Explore the large intestine, supporting the frame of your pelvis, then arcing back toward your sacrum and tailbone (coccyx) for the rectum and anus.

• Move with awareness of your sexual and reproductive organs, a base of identity and creativity.

• Orient to the weighted fullness of the organs.

• Consciously widen your pelvic floor: tail back, pelvis stable and horizontal. If tethered to the tail or pelvic floor, you may experience spontaneous elongation of the organs upward.

• You won’t get there by working or trying. Follow the pointers, yield to the exploration.

• When you get energy flowing in two directions, organs are expansive. All organs have movement, contracting and releasing in spiral flow. Let them move you.

TO WRITE

Fire and You

60 minutes

How does fire register in your body? When is it useful and when destructive? Consider both the volume body and the agency body. Write out ahead of yourself, and see what you find (10 minutes). Now, take this as the beginning for a whole new series of writings. Access fire in your language, and notice what emerges.

Photograph © Susan Lirakis

STUDIO NOTES

CARYN MCHOSE leads a class for our Body and Earth training at Pen Pynfarch in Wales (2010):

Core strength is reflective of appropriate orientation.

Volume body is our visceral body that gives us a sense of volume and feeling; it’s our interoceptive gut body.

Agency body is our action body, with an axis that moves us through space; it’s our exteroceptive skeletal-muscular system. (See Day 25 for more on exteroceptors and interoceptors.)

How are we supported? That story begins at birth, as our caregivers carry us. They are our backing, transporting us and giving us a feeling of support while we develop ourselves through expression of our needs. The process of developing a full and vibrant being strengthens us. We make a transition from feeling supported to acting in the world authentically without sacrificing our volume.

You can experience this in duets, leaning into each other:

• With a partner, seated, begin by being held—giving over agency and feeling support. Take time to feel fully held.

• As you separate from your caregiver (pushing, rolling away—becoming independent), your own axis comes online. When you leave, it’s not like you’re leaving. You have a sense of support.

We need our own sense of volume when presented with life’s dilemmas. In the evolutionary model, we find our volume through working with the cell, vessel, and fish. In experiential anatomy, we check in to some of the anatomy “bits” to refresh our orientation. We may notice places that have been compromised, confused, or compressed in the process of finding our way in the world. Clarity in evolutionary patterns and differentiating the body through experiential anatomy remind us that we can be more easeful in our connection to context.

The first question is the tonic function story: Where am I?

We all have our backing, and we all feel how we don’t have our backing. Work with inner exchange between your volume and agency bodies. We can use these orientation skills—a sense of volume that connects us to weight and Earth; and a sense of agency that takes us into the action space, fully supported by the ground—to meet challenges in our lives.