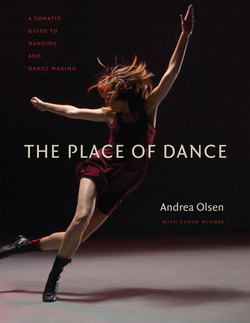

Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 8

Dancer: Steve Paxton

São Paulo, Brazil

Photograph © Gil Grossi (2000)

Looking Back, Moving Forward

Historical Perspectives

Great stylistic periods are singularly appropriate metaphors for the frames of mind of each period.

—Dr. John M. Wilson

Dance history comes in several forms: lived history, or what you are doing right now; researched history, or the stories and reflections of those who write and record; and imagined history, or the ways you insert yourself into other times and places. Seeing and reading about other artists’ work through time and comparing aesthetic values can deepen an embodied practice, enlarging your view.

Kwakiutl, Pacific Northwest Coast Kwakiutl tribe known for elaborate ceremonies often involving dance

“Dancing to restore an eclipsed moon” (Nov. 13, 1914)

Photograph by Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Edward S. Curtis Collection, LC-USZ62-73627

Within a career, there are times when looking back allows you to move forward. Certain aspects of dancing emerge through your unique self, and some come from the collective currents of your time and perspective on other eras. All are relevant in dancing and dance making. Although research can seem intimidating when you are creating your own work, history is an essential component of a rich and dimensional art form. Finding time to investigate this domain can activate your imagination—and create excitement about the broad scope of your field.

Dance, as the mother of all art forms, has been central to human experience since Homo sapiens stood on two feet and discovered the agility required by that unstable stance. Our look at this 125,000-year history begins on American soil. Native peoples and their dances arrived on the North American continent about 12,000–30,000 years ago. From the 1600s on, immigrant dance forms from every continent and culture added new dimensions to the indigenous lineage. European, African, and Asian styles and traditions intersected through ballet, jazz, tap, Afro-Caribbean dance, martial arts, and other distinct global forms, inspiring popular culture and dance culture. The weave of what became modern dance continues on a mercurial path to the dance you are making—your own contemporary work.

Considering Twentieth-Century Modern Dance in the United States

One way to view dance history as an art maker is to look at the various images of what it means to be human, as reflected in different cultural contexts, movement styles, and individuals.1 Within the limited frame of contemporary modern dance in the United States, your focus (interests and sympathies) will reveal values and interconnections across place and time. For example, starting with a study of Denishawn, you’ll find a tour in Asia. If you begin with George Balanchine, you’ll trace a ballet heritage from Italy, to France, and to Russia before arriving in the United States. If you look at the footwork of Fred Astaire, Sandman Sims, or Brenda Buffalino, you’ll be amid the drumbeats and dances of Africa and the cloggers of Europe. History interweaves with the present moment—it’s inherently interdisciplinary, global, and revealing.

Loie Fuller (1902)

Photograph by Frederick W. Glasier (1866–1950) Black-and-white, copy from glass plate negative, 8 x 10 in., Negative No. 638

Collection of the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Archives

Then you might ask, What’s been left out of research and historical record? Not from political correctness or to disparage yourself, but to consider what an opportunity there is to enrich the story—to host an expanded conversation. Often it’s native traditions, people of color, and women. But change the lens that determines how you view any time period, and you find a distinct perspective. For example, you can reflect on dance in the United States from a regional rather than a New York City–centric perspective; through gender, culture, race, class, and age; via various academic disciplines; or through your own unique interests and affinities. From neuroscience to anthropology, all fields of study partner with dance in the unfolding understanding of what it means to be human on this planet.

This chapter is not a comprehensive study; it’s an invitation. There’s a danger in listing names and describing political and social movements: artists are left out. Yet researching just one will lead you to many others, including the matrix of elegant performers, composers, and designers who shape the theater experience. Remembering that what was once “cutting edge” in modern dance becomes classical as it is sustained and passed on through time, you can view some of the styles and forms still with us today. Note that artists’ lives and work span decades—Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham each left more than seventy years of dance making. When you see announcements of workshops, auditions, and performances, there’s a lineage you can trace, a web of connections to investigate.

To engage historical perspective, look around. Read papers, books, and dance journals, and go to concerts. Check online sources for any of the artists listed in this book, and see where the search takes you. There’s much more than is on these pages.

The true dance must be the transmission of the Earth’s energy through the body.

—Isadora Duncan

Isadora Duncan

Photograph © Edward Steichen (1921)

At the turn of the twentieth century, three daring women were moving issues of dress reform and women’s rights forward through dance. Loie Fuller was known for her pioneering investigations with lighting effects and fabric, at the advent of electricity. Isadora Duncan danced barefoot and adopted the Greek tunic for expressive dancing, with movement motivated by impulses emanating spontaneously from the solar plexus. And Ruth St. Denis was an advocate of health, spirituality, and all things “Oriental.” These innovators demonstrated women’s inner independence and went to Europe for affirmation. Extolling the body as a source of inspiration, they captivated thousands of viewers in the United States and abroad, changing the course of dancing.2

The Paris Exposition of 1900 featured Fuller performing her Danses Lumineuses at the Art Nouveau Theatre built just for her, with the younger Isadora and Ruth as viewers. In 1909, while Isadora toured America, the Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev brought the Ballet Russes from Moscow to Paris. French ballet had fallen into decadence, so audiences were stunned by the expressive and virtuosic dancing, featuring choreography by Mikhail Fokine and performers such as Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova. Ballet Russes, commissioning daring sets, costumes, and music by collaborators, created a synthesis of art forms, merging contemporary values with classical tradition.3

The effect of the Ballet Russes in America over the next decades, through touring, emigration, and immigration, was a refined ballet lineage. Visionary arts patron Lincoln Kirstein invited George Balanchine to found the American Ballet Theatre in 1933 (later the New York City Ballet).4 Other Russian-trained dancers opened studios across the country, offering quality instruction. Ballet, with origins in the royal court of Louis XIV, modeled verticality (mind over body), with a high center of gravity and presentational focus. Balanchine, interfacing with the spirited American music and earthbound modern dancers of the 1930s, explored new patterns of form and movement in space, stripped of decorative detail—with his motto “Less is more.”5

Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn duet

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-35093

I am not a music dancer, I’m an idea dancer.

—Ruth St. Denis

In the second decade, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, evangelistic by nature, began collaborating. They married in 1914, and formed the Denishawn company and school in 1915 to spread dance across America. Partner dancing and orientalism were the rage, and their repertory featured both. Known for inhabiting and imitating the dances of others (Indian, Asian, Egyptian, Aztec, and Native American—whatever caught their imagination), they made theatrical dances of all forms and scales, based on images and ideas. Viewing Denishawn amplified the idea that each person has within the self the full range of what it means to be human—we are each “the other.” With a repertory both illuminating and entertaining, including sometimes thirty dances in a concert, they spent months on the road (fifty performances in a row), steaming across the country by train, collecting local dancers to fill roles.

During the 1920s to 1930s, the Denishawn School trained performers, peopled silent films, and cultivated a next generation of dancers. Daily class in California might include yoga meditation, Delsarte (a system of healthful exercises), ballet barre, cultural forms (Japanese or Indian dance), and private lessons with Miss Ruth. In 1925 to 1926, the couple embarked on a tour of Asia and India, performing their eclectic dances, and in some cases reinspiring respect for traditional forms in the regions where they toured. After the couple separated in 1931, Shawn formed a men’s company (1931–1940), taught dance at Springfield College (a preeminent school for physical education), and founded Jacob’s Pillow, an ongoing summer program in Massachusetts (Ted Shawn Theatre, 1942). St. Denis founded the dance program at Adelphi University (1938), and continued to teach and create until her death in 1968.

Martha Graham

Lamentation

Photograph by Soichi Sunami, Estate of Soichi Sunami

Dancing is just discovery, discovery, discovery.

—Martha Graham

Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Wiedman were three of the four recognized “pioneers of American modern dance.” They performed with Denishawn for a decade before setting out on their own in the late 1920s. Musical director Louis Horst, accompanist for Denishawn and later partner to Graham, influenced the teaching of dance composition and the trajectory of contemporary composers and visual artists who would collaborate with modern choreographers. Those who worked with Graham include such artists as Jean Rosenthal in lighting design, Aaron Copeland as composer, and Isamu Noguchi in set design. John Martin, dance critic for the New York Times, was central in bringing modern dance to the forefront through his articulation of the intersection of new forms and their content, conveying their meaning to the viewer.

Martha Graham Letter to the World (1940)

Photograph © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

The man who speaks with primordial images speaks with a thousand tongues.

—Carl Jung

Graham took choreography seriously. She was the first dancer who graduated from college, attending the Comstock School in California. The daughter of a medical doctor who specialized in treating psychological disorders, Graham was financially and socially stable and secure (unlike previous American dancers). She was interested in “dancing from the inside out,” that is, exploring psychological motivations, a goal shared by many dancers at the time. Her intellectual depth and drive underscored the impeccable technique she created to support her choreography, based on the principle of contract and release. Centered in the abdomen—the creative and sexual center of the body—and amplified by breath cycles, the “inner impulse” was made manifest in passionate and expressive action.

Dancer and Choreographer: José Limón Mexican Suite (1944) Vintage gelatin silver print, titled on verso, 4 x 4¾ in. Bruce Silverstein Galleries

Photograph © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

Graham’s first company of three women formed in 1927 (the year of Isadora’s death), followed by a company of twelve women in 1929. The first male dancer, Erick Hawkins (her future husband), joined the company in 1938; this was one of many shifts during decades of work within a theater space magically lit by Jean Rosenthal. Inspiration came from many sources, including Graham’s fascination with Greece and mythology, and her longterm involvement with Jungian therapeutic principles and ideas—exploring archetypal dimensions of body and psyche.

Doris Humphrey worked with the principle of fall and recovery—pendular movement, described as “the arc between two deaths.” Breath rhythms supported musicality, lyricism, and a compositional eye. Her book, The Art of Making Dances, remains a classic. With Charles Wiedman, she formed the Humphrey-Wiedman Dance Company in 1928, with each artist focusing on her or his own repertory. Charles was best known for his humor and wit onstage, creating solos and group work for male dancers. When Doris stopped dancing in 1945 because of arthritis in her hip, her protégé, Mexican-born dancer José Limón, continued the work and developed his own artistic voice, creating masterpieces still being performed by the José Limón Dance Company.

The fourth pioneer was German expatriate Hanya Holm, a student of Mary Wigman in the lineage of Rudolf Laban. This heritage combined clear systemization of methodologies with articulation of energy states and movement qualities. While choreographing and teaching, Holm passed on these principles at her school in New York City and Colorado College summer sessions. Alwin Nikolais was a primary student, followed by his protégé Murray Louis in New York and the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company in Utah; both dancers reflect the Wigman-Holm tradition in their work.

Beginning in 1934, these four pioneers taught together at the Bennington School of the Dance, founded by Martha Hill (now the American Dance Festival, held in North Carolina). This festival supported the creation of new choreography and cross-fertilization of work. Each artist would teach and premiere new repertory over the six-week session in a focused, yet highly competitive environment in rural Vermont. The festival provided resources not just for performers, but also for the new academicians in dance, shaping courses in major universities. Of the original matriarchs of college dance programs, Margaret H’Doubler at the University of Wisconsin–Madison established the first dance major (within physical education) in 1926, articulating a new layer of respectability, intellectual rigor, and creative and scholarly research for dance in the United States.

The dance is a spirit. It turns the body to liquid steel. It makes it vibrate like a guitar. The body can fly without wings. It can sing without voice. The dance is strong magic. The dance is life.

—Pearl Primus

Pearl Primus

Rock Daniel (1944)

Photograph © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

Dance and anthropology claimed each other as partners through the focused work of artist-scholars Katherine Dunham and Dr. Pearl Primus (nine years younger). Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, both in their distinct ways invested in researching and embodying traditional roots of the African and Caribbean lineage of American dance. Their work inspired the Pan-African movement in the Caribbean and challenged social norms in the United States. Other dynamic artists were also engaging cross-cultural and political issues. Leftist dance, the emergence of black urban dance, and the formation of the New Dance Group all had impact.6 Helen Tamiris, focusing on social concerns, took her creative work to Broadway, with Daniel Nagrin as featured performer. First in New York City and then in Los Angeles, Japanese-born Michio Ito created a unique East-West synthesis, influencing numerous artists, including Denishawn, before being deported to Japan during World War II (1941) and establishing his school in Tokyo.

Alvin Ailey and Carmen De Lavallade

Dedication to José Clemente Orozco

John Lindquist photograph (MS Thr 482) © Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Don’t try to dance like him or her. Dance like yourself.

—Lester Horton

In the 1940s through 1950s on the West Coast, Lester Horton collaborated with dancer Bella Lewitsky to develop a unique technique and performance group; establish one of the first permanent theaters in America devoted to dance, Dance Theater in Hollywood (1946); and organize one of the first integrated modern dance companies, including performers Carmen De Lavallade and Alvin Ailey. After Horton’s death in 1953, his legacy was continued by young Alvin Ailey, who moved east in 1958 and created his own theatrically imaginative company. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s mission includes “preserving the uniqueness of the African American cultural experience.” Featured dancer Judith Jamison became its next director, followed by Robert Battle in 2011.

The third generation of dance artists who formed companies in the 1950s also includes Erick Hawkins, Paul Taylor, and Merce Cunningham. Each danced with Martha Graham, yet each moved away from the dramatic narrative that characterized her work. The Erick Hawkins Dance Company, and Hawkins’s “free flow” technique, developed fluid, seemingly effortless dancing and influenced the emerging field of somatic practices. On the West Coast, pioneering dance artist Anna Halprin founded the influential Dancers Workshop in 1955, spearheading the expressive arts healing movement and engaging social issues.

Rather than practice [dancing], like the piano, I preferred the idea of adventure. Instead of saying no, you find out if you can say yes, you find out something more … We’re capable of many more physical things than we think. First of all it’s a question of changing your mind.

—Merce Cunningham

Merce Cunningham, founding his company in 1953, partnered with musician John Cage to engage “the power of the instant” and open uncharted territories. Graham’s emphasis was on psychological, dramatic themes. Cunningham wanted something without that weight; the drama was in the steps.7 Explorations included chance works reflecting Zen principles, and innovative (early and ongoing) interactions with technology. From Black Mountain College residencies with Cage and visual artists, Cunningham developed an entourage of collaborators including David Tudor, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jackson Pollock. The dance was independent onstage—holding its own in time and space as other elements moved, vibrated, and illuminated the space (like the giant Mylar pillows created by Andy Warhol for Rainforest with electronic score by Cage). Sometimes the music and costumes would be added the night of performance to ensure no premeditated connection.

Erick Hawkins

El Penitente (1940)

Photograph © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

Musician John Cage said that what he and Merce Cunningham were aiming for in their dances was “the imitation of nature in its manner of her operation.” In a meadow, a bird flies one direction, a rabbit runs another. 8

The Cunningham dance technique, central to the training of many dancers—even in the rebellious 1960s—requires a strong central axis with the capability and responsiveness to move from any point in the body, to any place in space, at any time. With a strong background in tap and ballroom, Cunningham engaged fast, rhythmically complex footwork, developing a technique that was comparable to ballet in its formality. With Cunningham, a new era was always beginning. Challenging for audiences, his “abstract” work required total absorption in the moment at hand; attention to larger systems and processes than the personal; and sometimes, the capacity to endure—sound, light, and abstract movement—with curiosity and a sense of humor. In 2009, Cunningham made his last work; it premiered on his ninetieth birthday.

Merce Cunningham

Totem Ancestor (1942)

Photograph © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

Basic dance—and I should qualify the word basic—is primarily concerned with motion. So immediately you will say, but the basketball player is concerned with motion. That is so—but he is not concerned with it primarily. His action is a means towards an end beyond motion. In basic dance the motion is its own end—that is, it is concerned with nothing beyond itself.

—Alwin Nikolais

Often called the father of multimedia theater, Alwin Nikolais was not only the choreographer, but the composer as well as the lighting and costume designer for all of his works. Nikolais studied with all the pioneers, working primarily with Hanya Holm. The Nikolais Dance Theater and school, founded in 1951 at the Henry Street Playhouse in New York City, incorporated daily improvisation and choreography and influenced generations of emerging artists throughout the world. In an age when Freudian imagery was dominant, Nikolais defined dance as the “art of motion,” and believed in the power and mystique inherent in abstraction, where motion, light, and sound were equal partners. Distinctive Nikolais works include Masks, Props, and Mobiles (1953); Totem (1960); and Count Down (1979).9

Merce talked about surprising oneself, about taking unexpected turns towards what you may not recognize. Murray always talked about energy, time, and space, about dancing like a spice jar (in the best of ways). Both images suggest envisioning consequence in a way. Marshal the body, sense the effect. Delicious. Fun. Hard.

—Bebe Miller

Collaborator Murray Louis performed with Nikolais and also formed his own company (Murray Louis Dance Company, 1953). His focused attention on physicality underlies the Nikolais-Louis technique. Other companies spawned from the Nikolais Dance Theater include the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company (Salt Lake City) and PearsonWidrig DanceTheater (New York City), among others. The often-cited characteristics of “wonder, delight, and mystery” were carried on by Pilobolus, founded by students at Dartmouth College with their teacher Alison Chase (1971) from her class on collaboration and improvisation, followed by the offshoot company Momix. Bebe Miller spent Saturday mornings from age four until twelve (1954–1962) crafting her mastery as a future choreographer in the Henry Street Playhouse, where Murray Louis taught classes for children and adults. Nikolais and Louis’s school continued into the 1990s at various locations in New York City.

All this exact training and dance stylization cannot abstract a body into a nonentity. A person is going to be revealed. […] Vanity, generosity, insecurity, warmth are some traits that have a way of coming into view. This is especially true of the kind of dance that, instead of representing specific characters, features dancing itself.

—Paul Taylor

Merce Cunningham and Carolyn Brown Crises (1960) Costumes: Robert Rauschenberg First performed at the 13th American Dance Festival

Photograph © John Wulp (1968), courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust