Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 6

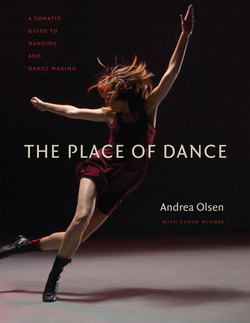

Dancer: Bebe Miller

Photograph © Julieta Cervantes

Training and Technique

Every lasting dance technique is based on anatomical truth.

—John M. Wilson, lecture

We train for the unknown. Dancing cultivates a personhood capable of meeting the art form. Like all awareness practices, dance requires a balance of study and practice, reflection and doing. Along with work in the studio, there’s history, anatomy, and aesthetics to engage, as well as understanding media and the collaborative art forms. Throughout, there’s the creative edge of invention. Dancing requires our largest selves. Our choices for training reflect this desire, this understanding.

Contemporary dance involves both orientation and disorientation: learning from the past, and determined investigation of the new. There is always a tug between training and invention. The stronger the formal technique, the firmer the ground in training. However, the more formal and repetitive the form, the harder it is to find movement invention. Part of dancing is the call to refresh the creative language; to move forward, shake things up, locate your self in new material, and inhabit and sustain an inventive edge. The correction in a technique class can be the expressive vocabulary of creative work: the “out-of-line” shoulder or the rebellious foot is a call for attention.

Different training techniques bring forth distinct qualities. Classical dance forms exist around the globe, including ballet, Bharatanatyam, and tango. Newer forms, such as modern dance at the turn of the twentieth century, reflect individualistic styles honed to create a particular aesthetic and to carry out a choreographic or performative vision. Most are deeply sourced in organic, natural laws and get codified so they can be passed on to others. Techniques in the history of American modern dance took this creative route, establishing training ground for dancers in their companies. The foundational styles of Martha Graham, José Limón, Lester Horton, Erick Hawkins, Merce Cunningham, Alwin Nikolais, and Katherine Dunham are a few of the many techniques still in currency today.

Anatomy offers a clear starting point for understanding efficiency across stylistic boundaries. Effective training programs seek balance in the body systems—the skeletal, muscle, organ, neuroendocrine, fluid, and connective tissue systems that comprise our structure. Identifying overworked areas of strength and weaker areas that need support affects training choices. Rather than continually reinforce the known—and burn out those systems from overuse—it’s important to locate opportunities for growth. Timing has impact: sometimes we need lots of input; at other points it’s best to follow one track in depth, with space to integrate and inhabit the work.

Everything we learn feeds dancing. Particularly when investigating movement through creative work, expanding life experience provides something to dance about. Intellectual, intuitive, and emotional range can be as important to training as building physical strength, endurance, and coordination. For those who have danced since childhood, there’s sometimes a need to rehabilitate relationship to dance—moving beyond injuries and stressful memories. Easing off physical training and looking for new pathways can expand horizons, supporting an individualized voice and unique vision.

What I Look for in a Performer (Tamar Rogoff)

BODY INTELLIGENCE

The will to investigate and to be experimental within a new approach

SENSITIVITY AND SENSUALITY

The ability to focus on the origin and pathway of a movement and everything that surrounds it

FOCUS

Being in the moment so that the experiential senses can play and energize the next movement event

UNIQUENESS

Filtering movement and images through a distinct matrix of self

EXCITEMENT ABOUT THE PROCESS

A sense of how the particularities of performer and choreographer, when melded, can evoke the universal for the audience

Becoming a dancer takes time and happens in an instant. Thinking like a dancer requires dancing—putting in your time. Attend class, move, or create consistently. Then the body responds. It resets the resting length of muscles; lays down more calcium in bones; adjusts breathing patterns and blood flow; and maps new brain connections and coordinations. Dancing once a week begins these changes, refreshing vitality. But immersing yourself initiates more substantive shifts. Summer workshops, dancing eight or more hours a day for several weeks, offer a new baseline for embodiment. More cells wake up—there’s no turning back.

In this era, we are fortunate to have available many training techniques, somatic practices, and spiritual modes of inquiry. One of the challenges is choosing what’s useful and committing to a practice. Dancing plays multiple roles in one’s life: it channels sexual energy and personal drive; offers a sense of control over sometimes-chaotic life; engages intellectual curiosity in ways that academic subjects may not achieve; offers a sense of community and identity; details a full-bodied pathway to art making; and provides access to spiritual realms through rituals such as class and performance, and through sublime moments. Choosing what training will enhance one’s development requires personal discernment about values and desires.

Change feels awkward. It may not be easy to let go of “being right” or “looking good.” Some dancers need to release muscles, while others need to strengthen. Muscles that have lost their capacity for resiliency can restrict movement. Sometimes bodywork or massage is needed to support opening to the next threshold of capability, particularly if the fascia surrounding muscles and organs is stuck from intense training. Somatic practices such as bodywork, the Alexander Technique, or the discipline of Authentic Movement that focus on body awareness are good partners to dancing. With the right practitioner, a session every other week can add enormously to health and flexibility, extending the longevity of a career.

Some dancers are performers first, not classroom dancers. Distinguishing permeable membranes between warming-up, dancing, and performing is an embodied experience. Sometimes most of a class can be spent warming up to dancing; sometimes dancing begins the moment you walk in the door. Knowing the difference, whether in technique, set work, or improvisation, requires the fresh mind of engagement. Dancing is not like exercising on a treadmill while watching television, making the body dull. Instead, dancing trains an awake, engaged, and inquisitive mind. This is the training for dancing—showing up, being present, and opening to what might move through us in the moment.

STORIES

Dialing In

There’s distinction among movement forms, and there’s specificity within each form. A student offers the image of radio frequencies: you tune in to specific stations. For example, you can discern in your body between Authentic Movement and Butoh, or between Limón and Horton techniques. And there’s also getting clear reception—eliminating static or overlapping signals. Sometimes you can be dancing with someone in contact improvisation, but she doesn’t really understand weight. It’s not a clear signal.

≈

A yoga teacher is asked, “How do you know when you are a master practitioner of yoga?” He responds, “You do yoga every day for ten years, and if you miss a day, you start counting over.” This affirms my experience in dance: it took ten years of professional dancing after graduate school to begin to understand the nature of performance. You learn dance by dancing; it’s larger than your ideas.

Committed Practice

A biography of Michelangelo noted that the artist drew his own hand every morning. Trying this for a year, I learned that drawing is a skill—not just an endowed gift. Dancing is the same. Sometimes you are rehearsing a dance and don’t have the “chops” required. More endurance, arm strength, or attention to detail is necessary. That’s an invitation to expand your range: run, lift weights, or take ballet. Building your tool kit is part of training.

Pelvis showing hip joints

© Alan Kimara Dixon

TO DO

Hip Reflex

5 minutes

Reflexes are our fastest, most efficient movement pathways, providing the basis of efficient training in dance and martial arts.

Standing, imagine a hot floor, nail, or piece of glass stimulating the sole of your foot. Notice the automatic reflex to flex the leg, folding hip, knee, and ankle simultaneously upward and inward toward center. This initiation is from the iliopsoas, integrating spine and leg—the fastest neuromuscular pattern for survival, and basic to martial arts training.

• Experience the hip reflex several times, and with each leg, to feel the action.

• Catch your knee in your hand. Fold the leg deeply toward your belly, emphasizing and feeling the deep crease.

• Extend the heel out into space, and lower your leg slowly to the ground.

• In contrast: lift your leg consciously. Notice if your thigh muscles bunch around the joint (and the knee goes slightly to the side). This reflects moving your leg from your quadriceps muscles, a less efficient action.

Even beginners can do deep reflexes, allowing release of the hamstring muscles through reciprocal innervation—as one muscle shortens, the opposite lengthens. The hip joint is a common place of tension. For efficiency at the hip, look for the reflexive pattern, the fastest, most efficient pathway in the body.

TO DANCE

Light-Touch Duets (Felice Wolfzahn)

20 minutes

Training includes comfort with skin-level contact.

Working in pairs, standing: Dancer A has eyes open, Dancer B has eyes closed.

• Dancer A strokes down the skin or cloth somewhere on Dancer B’s body. Use a light touch, so you aren’t pushing or moving your partner’s body. The touch creates a tingling sensation—stimulating light touch receptors in the skin (not muscle or bone).

• Dancer B receives the sensation (impression), and allows the body to respond (expression). Notice what instinctual action occurs. You don’t have to preplan or be interesting. Let this response settle.

• Dancer A strokes another place, using another body part (foot, shoulder, head). Make the stroke long and specific (not a poke or push), using light touch.

• Dancer B responds.

• Continue (5 minutes). Pause.

• Change roles: Dancer B touches; Dancer A closes eyes and receives.

• Continue (5 minutes). This will travel you through space. Keep noticing what you’re actually sensing, rather than anticipating your response.

• Pause. Take a few minutes to discuss your experience.

• Now, both have eyes open: alternate touching and being touched, with no words. Don’t worry if the sequence gets confused; just keep working (5 minutes).

• Now, dance your light-touch duet as solos. Each dancer works separately. Be clear about the imaginary stroke of stimulation, and then respond.

• Visually, this allows highly specific places of initiation for movement, unpredictable yet clear.

• Watch each other’s light-touch solos.

• Try this moving across the floor, first with one partner touching, and then again, soloing on your own.

• Reverse roles.

• Enjoy light-touch duets as part of your creative tool kit.

TO WRITE

Identify Your Strengths and Weaknesses

20 minutes

Discuss your areas of strength and weakness as a dancer, along with training techniques that support your growth—some make you feel great, some push your edge. What might be useful to move your dancing forward? Consider your personal response to these questions: What is technique? What are you training for?

Photograph © Paul H. Taylor

STUDIO NOTES

JEANINE DURNING teaches and investigates technique in a movement workshop at Middlebury College (2011):

What creates a generative state and what limits one? What serves your inquiry?

Seated on the floor, begin moving:

• Notice outside the body, notice inside: the air, the room, your breath, and where your body is touching the floor.

• Have a real inquiry into movement, not a fixed agenda. Be curious.

• Notice how you’re supporting yourself along the floor.

• Focus attention inside, attention outside.

• Keep the folds of the body malleable.

• Soften elbows: push against the floor with your hands, to initiate sliding across the surface.

• Soften knees: push against the floor with your feet to initiate sliding.

• As you continue pushing and sliding, focus on the folds of the body, folding toward center and extending through space.

• These two things, folding and extending parts of the body, are happening all the time; let’s bring awareness to it. Fold and extend the arms and legs, but also the spine, skeleton, fingers, and toes.

• Your body is constantly sliding as you shift your weight through space—focus on everything coming into the center, and moving away from the center.

• Remember the eyes. Remember to see.

• Shifting, folding, and extending: keep a malleable skeleton, with lots of space in the joints.

• Imagine swimming through water.

• Consciously engage your arms. Shift between hands and feet, supporting yourself on your feet, on your hands.

• If you space out, click your fingers.

Multiplicity: With Partners

• Working in trios: Person A, with eyes closed, lies in an X on the floor. Partners B and C move person A’s body, folding and extending. Be curious about how body A can move while noticing how your body also moves to move that body. Explore; then change roles so each person gets a turn being moved.

• When all three have finished, continue the same exploration, but with eyes open and attention toward space, direction, and will. Notice where you have leverage from the floor and from contact with others.

• Activate a little more through relationship to the floor and points of contact, sending the body into space.

Consider:

• How do you remember the specificity, detail, and “it-ness” of movement generated by improvisation for your own choreographic work?

• Technique is being able to adapt to any unknown situation in real time in relation to the parameters or conditions you are pre-given.