Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 3

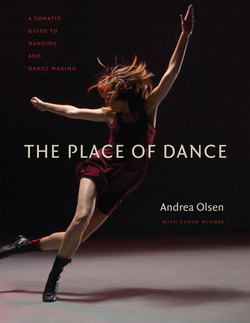

Bebe Miller Company

Dancers: Angie Hauser and Darrell Jones

Photograph © Robert Flynt (2004)

Flow

What We Can Count On

We are basically fluid beings that have arrived on land.

—Emilie Conrad, Continuum founder

Flow is our oceanic heritage. As we focus on the sensations of flow throughout the body, we recognize that it exists in varying degrees and can be diminished or enhanced through attention. Understanding the feeling of flow and maintaining connection with this internal sense of fluidity in our busy days takes practice.

Our inner body and the Earth’s surface are both largely water, most of which is salty. Life-supporting oxygen enters the body as breath, and is pumped by the heart to every cell in the body through blood. The flow of breath as blood is an expression of the life force that begins, sustains, and ends life. Words in many languages attempt to describe this animating presence, including prana, chi, life force—and dance.

How do we limit flow in dancing? Sometimes when we feel anxiety about beginning a project or making decisions, we contract or become fixated on preset, preformed views. But dancing and art making require fresh forms of being. When fixation limits expression, it can be useful to let go of form altogether and reconnect to flow. Attention to the fluid system of the body connects all the parts. Gently shaking the “blood side of the skin,” the insides, helps us feel the ripples and responsiveness of fluid, rather than rigidity.1

To enhance flow, imagine the body as a sphere—undifferentiated and full of fluid. Using the metaphor of a single cell suspended in the ocean, we can return to a place of all possibility in movement. The semipermeable cell membrane connects us to and also separates us from context (the environment), defining inner and outer. Skin is both touching and being touched. Each cell condenses and expands through cellular respiration, a metabolic process. Expressing itself equally in all directions, the cell has omnidirectional volume. We can be moved by content (inner fluids) and by context (outer ocean). Throughout, there is permeability and fluidity when we make choices.

Dancing is an ongoing dialogue between flow and form: forming in flow and flowing in form. Rhythmic flow is a source for dance, an underlying current—not just the drum machine pulsing out the heartbeat to get us moving, but polyrhythmic pathways inherent in our body systems. Flow enhances our ability to move rhythm throughout our structure, and to feel it opening stuck places from inside. One’s internal, individual flow meets the external rhythms of music, other dancers, and the choreographer’s directions. The invitation is to maintain personal integrity while dancing with and for others.

The movement of life is constantly re-creating, replenishing, and refreshing itself. All qualities inherent in water are present in our fluid bodies, from the slowest trickle to the crashing of waves. Balance, stretch, and extension while dancing are not goals in themselves; they reflect this flow of life force seeping, resting, or flooding through structure—as well as to others and place. Entering flow enhances our ability to inhabit new rhythms and new forms, responding, responsible.

STORIES

Dancing with Water

As a child living by the Atlantic Ocean in Florida, I was once pulled out and down by the undertow. It tumbled me against rock and sand, and then spat me out. The power was immense. I learned, forever, that water can kill you. Nature is not just pretty.

≈

Teaching in Bern, Switzerland, our dance host Malcolm Manning takes us to the river. “Walk upstream,” he instructs, “and jump in.” The calcium content is so high here that our fluid-filled bodies float, carried by the strong current. He reminds us to get to the edge and pull out before going over the dam. I feel a moment of panic, then ecstatic release as my body is swept along. Our group bobs and flows together—water inside, water outside.

Staying above Water

Indonesian dancer Suprapto Suryodarmo asks, “How to be under the water and see the horizon? A performer has to be aware of the horizon.”

Pools and Gods

The Yumban culture in Ecuador celebrated seasonal shifts with water. Visiting Tulipe, a pre-Incan archaeological site some 8,000 years old, we are shown seven pools. Stairs descend into each, and the last is in the shape of a jaguar. The expanse of the area faces a hillside contoured for seating. A guide suggests that the site was used by shamans in magical-religious ceremonies at equinoxes and solstices, with water as a purification element.

“There’s one more pool,” says the guide, “but you have to walk down along the river.” We take the hike, arriving at what would have been a water-filled circle, 1,000 feet in diameter surrounded by five tiers of stone seating. Lined with white sand carried all the way from the coast, at night the pool reflects the stars; constellations from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres are visible.

A raised “runway” extends to the center of the pool, with a circular tip large enough for two people. At solstice, this axis lines up perfectly with the sun. Strings are visible where scientists are measuring the preciseness of angles; at the equator no shadow is cast at noon. Closing my eyes and moving, it’s easy to imagine music and dancing, the celebrants walking slowly down the center, surrounded by water.

Hally Sheely, hands with tadpole

Photograph © Caryn McHose

TO DO

Rolling and Pouring (Caryn McHose)

15 minutes

Sometimes you need to reestablish flow in the body.

Lying on the floor, eyes closed:

• Imagine yourself as a water balloon. Gently roll the balloon, by pouring the water—your contents—from inside. (Like an amoeba, the cytoplasm pours into the membrane, creating movement through a pseudopod.)

• Roll from the membrane—the container—allowing your skin to meet space and the ground.

• Roll imagining a fluid environment—your context—moving your body.

• Explore this with eyes open; notice when you are moving with awareness of container (skin), contents (fluid insides), or context (outside).

• Engage the theater of your imagination. Move freely, allowing the body to respond. What does your body feel like doing now?

After enhancing sensory impression with rolling and pouring, engage sensory expression: speak or write about your experience, “squeezing back the sponge.”

Spinal curves

Photograph © Alan Kimara Dixon

TO DO

Spherical Awareness—Three Body Weights (Caryn McHose)

15 minutes

Remembering the roundness of the three body weights (skull, ribs, and pelvis) releases tension.

Continue lying on the floor, eyes closed to enhance awareness of touch:

• Slowly roll the circumference of your skull on the floor. Take your time; the rolling of the skull moves your body. Sometimes it feels like a hard-boiled egg, slowly cracking and softening. Allow the sensation of touch to bring awareness of the globe of your skull. Roll to the top center of the skull; touch all the surfaces.

• Slowly roll the circumference of the ribs on the floor. Take your time, and allow the rolling of the ribs to move your body. Feel their dimensionality and resiliency. Explore the globe of your ribs.

• Slowly roll your pelvis on the floor. Take your time, allowing the bowl of your pelvis to be stimulated on all surfaces.

• Pause; then bring these three body weights into vertical alignment seated.

• Pour your weight up to standing.

• Fill your feet first, like pouring water into a glass; the head is last.

• Stand in vertical alignment, balancing the skull, ribs, and pelvis over the length of your feet. Feel the fluidity within vertical orientation.

• Move within an imaginary sphere of space, your kinesphere. Maintaining awareness of spherical movement, let the globes of your three body weights meet the spatial globe. Explore roundness in your movement. Feel the roundness inside, the roundness outside.

TO DANCE

Plumb-Line Falls

15 minutes

Shifting your weight through plumb line creates movement—toward relevé and balance, or into space. Staying fluid in this process invites spacious movement.

Standing, eyes closed:

• Tap the top of your head and imagine a weighted plumb line dropping down through the center of your body until it touches the ground between your feet.2 Continue down to the center of the Earth, where all plumb lines would meet.

• Now, grow your plumb line upward toward the ceiling or a favorite star.

• Align your three body weights (skull, ribs, and pelvis) around this imaginary plumb line, balanced over your base—the length of your feet.

• Now, shift your plumb line beyond the base of your feet, initiating walking.

• Take a walk, elongating in two directions, bonding with gravity and bonding with space.

• Return to the sense of fluidity in your body. Practice falling into walking or running, moving before you’re ready.

• Keep falling, exploring fluidity within moving; your fluid dancing body is oriented to weight and to space.

• Now, dance your fluid dance; dissolve all your bones and body structures—return to the sea of fluid movement.

TO WRITE

Letting Words Flow

20 minutes

What do you long for at this time? From this book, from your current experience, from your deep self, write about your longing. Put your pen to the page, begin “I long for …,” and keep writing for 10 minutes—let the words flow. Writing, like dancing, requires endurance and is full of surprises. Keep this writing private, a conversation with yourself. Encourage longing and language to meet. Continue with “I don’t long for …,” and write for 10 more minutes.

Photograph © Julieta Cervantes

STUDIO NOTES

KATHLEEN HERMESDORF teaches a technique class at the Bates Dance Festival with musician Albert Mathias (2010):

Flow in dancing can be inspired through touch.

Keeping the energy moving:

• Move across the floor, engaging space from one side of the room to the other.

• Next pass, as you travel, partner yourself on the journey. Use light, receptive, responsive touch to add momentum, flow, and specificity. Feel yourself touching and being touched. Try this several times as you cross the room.

• For example, touch your head and give it a light push to direct your movement through space. Feel yourself being touched and touching. Take time.

• Try your hip: touch one hip and give it a spin through and into space.

• Move through various body parts, nonhierarchically and spontaneously—including and encompassing the whole body, without aversions or preferences.

• Then dance again as soloist, feeling as though you are still being partnered. Enjoy the specificity of initiation, the impulse to follow momentum and flow through space.

Working with a partner:

• Continue this process, but move across the floor with someone else doing the touching. It’s a duet; both partners keep moving through space, one person initiating the touching, the partner feeling and responding to the touching.

• Keep your own center while you are in dialogue; no shoving, forcing, or manipulating. It’s a touch conversation, with one person leading. Moderate the amount of pressure in the touch to indicate direction without forcing.

• Change roles.

• Thank your partner; check in if it feels useful.