Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 7

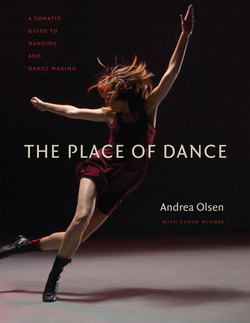

Choreographer and performer: Ann Carlson

Grass

Photograph © Mary Ellen Strom (2000)

Embracing Mystery

Earth and sky as one in the space of the unknown.

—Suprapto Suryodarmo

Dancing involves surrendering to something larger than the self. Moving and making give access to the mysterious pulse of life, willing us to be participants. If we deny energy and ecstasy—the place of mystery—in our lives, we are cut off from this deep, ancient resource. When we dance beyond muscle power, sense of control, endocrine high, buff physique, and societal praise; when we source more deeply, we open to the mystery within each moment.

Dancing is art making, a process of articulation. Art making requires that we value and prioritize a creative life. If we view dance as a life’s work, not a hobby, it offers a fruitful, intelligent, generous way to live to the fullest. The process of art making is very specific and in no way romantic. It builds one’s capacity to feel emotions when facing the immensity of life’s events. Courage, wisdom, justice, and reverence are required. Creating through dancing can keep you alive, focus your attention, and wake you up in the middle of the night. It can help you to love the world.

Ask yourself this question: do you see yourself as an artist or a student of art? And to answer, take a leap of faith. Open to your true nature. Consider yourself an artist, and everything you do will be filtered through this lens. Unfolding the creative self, with honesty and integrity, builds your house on solid ground. Not the ego self, the “I-am-ing” self, but the individual in pursuit of wholeness, all that is whole, holy. Daily you face the blank page, emptying to open.

There’s simultaneously the invitation to maintain a “beginner’s mind.” Approaching art making with this curiosity and freshness allows the “empty vessel” perspective of a lifelong student. Art making is an investigation and discovery, a pathway for research into knowing oneself and the world more fully. In this way you are both artist and student.

You can have collaborations, assistance, and conviviality: the friend who calls at just the right moment and asks a potent question; the colleague who adds new dimensions; a community of other artists, audience members, and critics who view your work and stay the course. These essential collaborators may remain with you throughout your life, pushing and supporting the edges of your work. But ultimately, the journey is yours.

STORIES

Moving Rock

Along the rock faces of Marloes Sands beach in southern Wales, Gill Clarke and I move together as part of a weeklong intensive. We are drawn to tumbled, horizontal boulders juxtaposed with vertical uplifts that form a kind of stage. Climbing, then closing our eyes, the impulse is to invert, ooze, and slide down the coarse surface like the molten lava it once was. Experiencing the abrasive granite bedrock as fluid counters logic. Who knew? Time shifts to timelessness. Moving at that speed, every cell finds its way. Arriving at Avebury Stone Circle in England, we walk on the 30-foot-high outer bank. How did these hundred standing stones get here? Who shaped the 1,400-foot-wide perimeter, and why? Groups are picnicking, dancing, strolling with children and dogs. We have come to mark World Environment Day with movement. After hours of viewing, we slip into dancing, like others have done for centuries. It’s a ritual site inviting participation, not functional but purposeful—like our dances.

≈

On the Gaspé Peninsula of Canada, I meander down to an isolated stretch of the Grand Cascapédia River. Picking up two stones, I close my eyes and begin moving, clicking the stones together. Another stone catches my attention, another dance. Sometimes, themes for a dance just need an invitation to call them forth. Over the next hour there are seven stones, seven dances, forming a whole—beginning to end—accompanied by water.

≈

Songwriter Paul Simon has described this receptive process: sometimes the song comes so fast, all he can do is catch it and write it down. If he hesitates, it’s gone.

≈

Colleague Caryn McHose is drawn to stones: she can sit for hours at the water’s edge, looking, feeling, and collecting. I watch, now, as she chooses tiny pebbles from a beach in Giovinazzo, near Bari in Italy. Her absorbed focus gives me vicarious pleasure. In meditation terms, I am practicing sympathetic joy.

INVESTIGATION INTO AUTHENTIC MOVEMENT

In 1979, after seven years of performing and teaching professionally as a dancer, I began writing a book on dance choreography. I wrote thirteen chapters (on rehearsal process, partnering, the use of space …) before I got to the section on movement and realized I had nothing to say. I was trained in the modern dance vocabularies of Martha Graham, José Limón, and Erick Hawkins, and in ballet, but I had no idea how my own movement was sourced. At that point I met movement therapist Janet Adler, who introduced me to Authentic Movement. She was interested in working with dancers and choreographers because she felt that much of what she saw in her studio was more compelling than what she saw onstage. I began working in Authentic Movement, and for over a decade I have remained fascinated by its richness as a catalyst for creative work and for healing. Since writing this article, reflecting on the origins of my involvement, I still move with two colleagues from that initial movement group: Susan Waltner and Alton Wasson.

Organ model with lungs and diaphragm

© Alan Kimara Dixon

TO DO

Breathing Spot (Caryn McHose)

15 minutes

Breath links both conscious and unconscious (autonomic) aspects of the nervous system, providing a link to the mysterious dialogue between inner and outer awareness.

Kneel in the deep-fold position, forehead resting on your thighs or the floor (child pose in yoga).

• Place your hands on your lower back, and feel the skin expand and condense as you breathe. Take your time. Be patient. Breathing is essential; it takes time to unwind holding patterns.

• Volumize the body with each breath: the inhalation can be used to touch your own volume inside. Exhalation is a time to surrender, yield, and release.

With a partner:

• Partner A rests in the deep-fold position.

• Partner B places his or her hands on the low-back area, resting them lightly to receive and guide the sensation of the breath.

Be patient; it might take time to wake up back-surface sensation.

TO DO

Three-Part Breath

15 minutes

Releasing holding of muscles and organs of the abdomen can enhance breath.

Lying comfortably on your back:

• Place your hands on your belly. Breathe into this area.

• Imagine a heavy book on your belly; let it rise and fall with each breath.

• Touch your lower ribs. On the in-breath, fill the belly and then expand the circumference of your lower ribs. On the out-breath, soften or condense these areas.

• Touch your upper ribs, under the collarbone and armpits. On the in-breath, fill the belly area, then expand the ribs, and then lift and expand the upper thorax.

• Repeat the three-part breath several times; the bottom fills first.

Eventually, you can exaggerate the movement less. Abdominal support in the front body is active, and the organs are free to move.

TO DANCE

Refreshing What’s Needed—Dancing with a Partner (Susanna Recchia)

15 minutes

Working with a partner activates connection, both to self and to other.

Begin walking, and place your hand on the upper back of someone in the room, then lightly stroke from upper to lower spine.

• Following the sensation of touch, both movers release their body weight toward the floor, starting with the head and upper spine.

• Roll and stand individually; resume walking. You may touch or be touched at any moment.

• Touch a new partner, rolling down the spine to yield to the floor. Roll, stand, and walk.

• Repeat, keeping the rhythm of walking underlying your exploration. Avoid talking, so you can focus on the sensations of touching and being touched.

• Pause. Find a new partner.

• The toucher places one hand on the partner’s upper back area, behind the heart; prepare to move with your partner in this position.

• Mover: As you feel support in your back-space, begin to move through the room. Dance so that your partner can follow wherever you go, supporting your movement with touch.

• Change roles.

• Repeat, becoming familiar with the process.

• Pause. Notice how support from the back-space affects moving forward. Discuss.

TO WRITE

What’s Your Experience of Mystery?

20 minutes

How do you name and access mystery in your dancing? Some moments in life have a particular shimmer or glow—a sense of unity beyond the parts. Where else do you engage this quality? Being conscious of your aesthetic values, your preferences, dislikes, and edge of comfort, explore your experience of mystery.

Prapto at Samuan Tiga, Bali

Photograph © Körperperformance

STUDIO NOTES

SUPRAPTO SURYODARMO leads an outdoor workshop, Creation of the Light, at Goa Gajah Temple in Bedulu, Bali (2009):

Body needs spirit; spirit needs body.

I’m interested in channeling, transforming, and creating. This can be approached from receiving or from expressing first. Clearing is part of that.

Specificity of our body parts as instruments: to channel, or to express, or to receive, you need the body awake, specific.

Windowing: making windows into your home, your body self; making windows to look out of your home. Which track to choose?

Bend lower, more side-to-side pelvis.

Notice living bone.

Knees, elbow, heels. Good, good.

Slowly, slowly.

Dance with me one by one.

Garden image: harmony as ideal.

Moving in moving; moving in no moving; no moving in no moving.

Understand—under stand.

(Ending) Feel your shape; sustain it. Feel it as transparent. Air, wind moving through you. Feel your insides.

Okay, please if there is something to say. Thank you to those who comment.

Shall we work again?

Photograph © Alan Kimara Dixon

Being Seen, Being Moved: Authentic Movement and Performance, Part I

by Andrea Olsen

Can we trust ourselves?

Authentic Movement is derived from a process developed by Mary Starks Whitehouse, which she often referred to as “movement in depth.” Mary was schooled in the dance techniques of Mary Wigman and Martha Graham that invoked and gave form to energies and images from the unconscious. In the 1950s Mary shifted her orientation from artistic to personal and developmental aspects of dance, and began her lifework experiencing and describing the process of “moving and being moved.” Mary’s work influenced many students and associates, including dancers, therapists, and educators, and it is currently employed in diverse ways by practitioners across the country and in Europe. In 1981, two years after Mary’s death, Janet Adler formed the Mary Starks Whitehouse Institute to further study and articulate her experience of the discipline of Authentic Movement.*

The form for Authentic Movement, as taught to me by Janet Adler, is simple: there is a mover and a witness. The mover closes her or his eyes and waits for movement impulses—the process of being moved. The body is the guide, and the mover takes a ride on the movement impulses as they emerge. The witness observes, sustaining conscious awareness of her or his own experience and of the mover. After a period of time, the witness calls the movement session to a close, and there is a verbal dialogue about what has occurred. The mover speaks, and then the witness reflects back her or his own experience of the session without judging it.

Ultimately the goal is to internalize a discerning but nonjudgmental witness while moving so that we can observe ourselves without interrupting the natural flow of our movement. In this approach to Authentic Movement, the form provides a container in which to practice entering unconscious material, returning to consciousness, and reflecting on or shaping the experience through speaking or creative work.

Authentic Movement facilitates healing as the body guides us into stored memories and experiences and toward consciousness. Our history is stored in our body: evolutionary movement patterns, human developmental reflexes, and personal experience. As we close our eyes and allow ourselves to be moved, endless diversity emerges.

Much of what we correct in technique class, for example, can be a resource in creative work or a call for attention to physical healing. A lifted shoulder or a consistently twisted spine may be indications of personal history. Our imperfection is our gift. As we learn to listen to the language of the body, we have a choice about when and how to work with a particular movement. Part of injury and illness is the conflict between what we tell our body to do and what it needs to do for healing, recovery, expression, or safety. Part of healing is allowing the unexpressed to be expressed.

As we begin Authentic Movement, we may face basic fears: hatred of our body, fear of being empty inside, fear of stillness, fear of being alone, fear of not being loved. “I’m too fat. I’m too thin. If I’m not moving, I don’t exist. If I’m not seen, I’m nobody. If I don’t do something good, nobody will love me.” Although these statements may seem harsh, they occur again and again in movement sessions. As we close our eyes and listen to our bodies, there is also the potential of accepting ourselves just as we are.

As we replace fear with open waiting, we can learn how rich our inner world really is. Often students ask why their first experience with Authentic Movement is so serious, their first dances so sad. Generally, we push into the unconscious what we consider to be negative—our sadness, our meanness, our fear. But below that layer of unexpressed movement is the wealth of human experience. That is the resource from which we draw in Authentic Movement and which we hope to bring to the stage.

As we use Authentic Movement as a resource for choreography and performance, we are developing a dialogue with our unconscious. Basically, there are different sources of movement that have been described as the personal unconscious (personal story); the collective unconscious (transpersonal and cross-cultural); or the superconscious (connected to energies beyond the self).

Without limiting the spectrum of movement possibility, we might note particular modes of movement that emerge from these sources, including impulses based purely in sensation (such as stretching or attending to an injury); impulses based in reorienting our consciousness (such as spinning, walking backward, or rolling); impulses based in journeying (such as unfolding a movement story); or those based in emotionally charged or spiritually transformative states available in the body (such as hearing or speaking inner voices, ritual gestures, or visitations by specific characters). These sources and modes are ways of describing different aspects of our movement life, and are all part of the range of Authentic Movement.

Within the experience of “being moved” where the unconscious is speaking directly through the body, some motions or positions will be unformed or hard to remember, some developing, and others ready for consciousness. Movement that is “ready” returns again and again, is easy to remember, and is available, in my experience, for creative forming.

Movement that is unformed or developing needs time to unfold. As we consider dancing for a lifetime, we recognize that we have time to develop our creative and physical resources, so that we are not strip-mining our unconscious (using every movement that emerges and putting it onstage) or devouring the vital resources of our body (burn out now because we have only so many years to dance). Our body and our unconscious develop a dialogue with our conscious self—a pact of trust that is constantly being negotiated. For example, in an injury of the spine or the ankle, the muscles spasm to protect us from movement. (If we didn’t hurt, we would move!) As the body trusts that we will rest, the spasm can release. That is the negotiation.

Can we trust ourselves? In personal and developmental work, we have to know that a process of change can and will be supported. For example, if a difficult memory from childhood emerges in a movement session, the mover needs to trust that she or he has the resources and will take the time to integrate the experience into conscious awareness. Otherwise it is more appropriate for the memory to remain unconscious. By internalizing a supportive, nonjudgmental but discerning inner witness, we develop self-trust at a deep level.

Photograph © Alan Kimara Dixon

Being Seen, Being Moved: Authentic Movement and Performance, Part II

By Andrea Olsen

The discipline of Authentic Movement teaches us about the relationship between mover and watcher.

The relationship between the mover and the witness parallels that of performer and audience. The multiplicity of the human experience lives in each of us, and the stage provides an opportunity to embody our inner selves by moving as performer, or by empathizing or projecting as witness. This transference of awareness between the audience and the performer enables transformation for both. At first, the collective mind of the audience supports the surrender of the performer to unconscious energies, but soon the audience surrenders its awareness of self and goes with the performer toward transformation as well. In this context, transformation becomes an inclusive experience. For example, in China during a solo concert, when I dropped my head, the heads in the room would drop; when I lifted my focus, the audience’s focus would follow my movement. Performance became an environment in which people who were seeing could be moved.

In my experience, if I am performing well, I am witnessing a moving audience. I am holding the witness role as dancer, the audience is the mover, and I am supporting their journey. Thus, part of the practice of performing Authentic Movement is the practice of community. At these times, dance becomes a vehicle for energies beyond the self that can be invited, or invoked, but certainly not forced. This exchange exists as an aspect of “being moved” that is available to each of us.

Within the spectrum of collective experience, there is a tremendous relief, both as a mover and as a watcher, as we realize that we are participants in a larger whole. If we are attentive to our unconscious, and others to theirs, there is inherent order, unfolding, and relationship that occurs. Group work in Authentic Movement includes experiences of synchronicity, simultaneity, cross-cultural motifs, feats of endurance or strength, interactions with other people and other energies in the room, extraordinary lifts, and dynamics that could never be planned or practiced. Injuries are rare; if the body and psyche are working as one, anything seems possible and true limits are respected.

Encountering others in group work allows development of trust at a profound level. The basic “rule” in group sessions, eyes closed, is that you follow your own impulses. In the moment of contact, the choice to move with another person is based on whether you can stay true to your own inner impulses while working in contact with another person. As each person follows his or her own impulses, no one is “responsible” for taking care of anyone else. We long to be seen for who we are in our totality, not for the limited view of who we present ourselves to be, or who others imagine or want us to be. The practice of Authentic Movement in group work is the practice of being true to who we are in the presence of others.

There are several ways in which Authentic Movement is useful in performance. Authentic Movement informs performance. Its practice gives us information about our own personal movement material that helps us decide whether to explore it for ourselves in the studio, extend it into therapeutic work, or bring it to the stage. One of my earliest discoveries with Authentic Movement was how much the body has to tell us. Simply by letting my body move me instead of trying to control it, fascinating movement and useful insights would emerge. I felt the expansiveness of my own vocabulary as a dancer, rather than wondering if I could come up with one more evocative or unusual movement in the studio. When I taught a group of students, the same richness was present in each person’s movement. It was a humbling lesson in the universality of individual uniqueness.

Authentic Movement also informs our viewing of dance. As we practice witnessing, we begin to recognize authentic states and become aware of our own projection, noticing the extent to which what we are reading into someone’s movement is our own material, how much is theirs, or how much is a shared state. Then we can more clearly identify unconscious content in our own work—read our own dances, and facilitate others to notice their unique movement language. Whether Authentic Movement is the criterion we want to use to watch performance is a choice; it informs, but it is only one of many ways to view movement.

Authentic Movement is also a resource for performance. The ongoing practice of Authentic Movement provides a scrapbook of images, movements, and energetic states that can be drawn on in the choreographic process or in an improvisational performance. In my early work with Authentic Movement, I felt that the practice gave me the emotional subtext for a dance. For example, the first full-evening piece that I created from Authentic Movement was called In My House, and it unfolded in its entirety in a one-morning Authentic Movement session—seven sections with specific movement vocabulary. I could develop it any way I wanted, but the emotional and structural clarity had been established within me.

For performers, the practice allows movement patterns learned from others to become integrated with personal experience. Sessions also facilitate a kind of housecleaning of habitual movement patterns that need to be processed at the level of the unconscious and released before beginning new work.

Authentic Movement also exists as performance. An increasing number of dancers are presenting the practice of Authentic Movement in a performance context. In questioning whether the Authentic Movement experience itself is transmittable or whether it needs another form or frame to allow for transmission, I participated in an Authentic Movement performance series with a core group of dancers who had worked together in Authentic Movement for many years. We tried five monthly performances and after each, one or more of the performers was sick—with the flu, for example.

We had used Authentic Movement in choreographed work quite a lot, and in other forms of improvisation without problems, so we tried variations to develop a safer container for showing the work: adding music, having eyes open, having a witness in the audience, having some performers who were sourcing in a more traditional dance mode, as well as presenting the pure practice as performance. Eventually we considered two possible causes of the post-performance illnesses: while performing, we were merging with our watchers and were not establishing boundaries, so we picked up whatever was present emotionally and physically in the room, overloading our systems; or we were exposing unconscious material that needed the process of dialoguing directly afterward for completion.

Regardless of whether the raw authentic movement state can be sustained and transmitted in a performance setting, it is generally agreed that “good” performance—choreography, improvisation, Authentic Movement, and so on—is authentic. It includes the sensation of moving and being moved, a merging of unconscious and conscious states, and a moment-by-moment unfolding of the performer and the work.

As Authentic Movement informs performance, the underlying motive and hence the nature of performance changes. There are years in performance when we may be driven by our need to be seen, when our ego seeks validation, when we must shape and control, when we desire to transform and know other parts of ourselves, or when we are compelled to create rituals of experience for others. These motivations may change during our lives as performers. Dancing at twenty is different from dancing at forty or sixty.

At a mature level, a performer has an articulate, discerning inner witness that allows authentic connections to occur onstage. As we internalize our own witness and lose, in effect, our need to be seen by others, new performance motivations arise. What might these be? The practice of being seen being authentic, in an era where the superficial takes precedence. The practice of connecting to energies beyond the self, in an era where spirituality is shapeless. The practice of participating in a community of exchange between dancers and watchers, in an era where dance has been removed from most people’s lives.

Authentic Movement points to a process of recognition between mover and witness, performer and audience. As we feel seen, we can see. As we feel heard, we can begin to hear others. As we develop an articulate and supportive inner witness, we can allow others their own experience of moving and being moved. The process of listening to the movement stories of our bodies encourages us to know ourselves and to bring this awareness to performance.

*See Janet Adler, “Presence: From Autism to the Discipline of Authentic Movement, an Address by Janet Adler,” Contact Quarterly 31 (2) (Summer/Fall 2006), 11.

Source: Contact Quarterly 18 (1) (Winter/Spring 1993), 46–53. Also see Pallaro 2007. Used by permission of the publishers.