Читать книгу The Place of Dance - Andrea Olsen - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 5

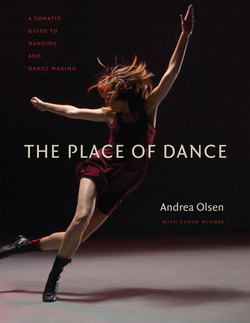

PearsonWidrig DanceTheater

Thaw

Photograph © Tom Caravaglia

Getting Started

The Creative Process

There are two qualities necessary as an artist: fidelity and originality. Fidelity because it takes so much work and time to bring something to fruition, and there will be times when you will want to leave it behind. Originality because you are making something new, something never experienced before.

—Terry Tempest Williams, lecture

You can only dance where you are: physically, psychologically, and emotionally. To get started, take stock. Notice what is actually happening in your body right now—not what you want to have happening, but the sensations detailing inner and outer landscapes at this moment in time. Then authenticity will flow through movement. Dance, the mother of all movement forms, requires honesty, truthfulness. This includes a commitment toward not harming self or others in the process of art making. You make ethical choices when you are working with other people’s bodies. Then the body will open. Taking stock allows you to arrive, fully in the moment, ready to begin.

Where do we go within ourselves to source, or locate, our dancing? How do we let movement impulses flow into expression without too much restriction or convention? What’s the pathway to our unique creative flow? How do we get there, know when we’ve arrived, and find our way back to daily life? Can we create the conditions to return to that dancing place at a different time, from a new direction, under challenging circumstances? What do we encounter on the way: blocks, moods, and diversions? Pleasures, excitement, awe? As we become familiar with our creative process, these waypoints are signposts, not obstructions.

The creative process takes time and tenacity. It seems everything conspires to dilute our attention. We generally have to give up something to procure time and to receive the muse of our creative life: cancel a party, ignore email, or skip a trip with a friend. Then we still have to get ourselves to the studio to dance. At first, making time for creativity feels like a hard choice, but eventually the flow will refresh.

A life of dance is not for the undisciplined. Especially for those who engage in the creative dimensions of performing, improvising, and choreographing, dancing will lead to surprising aspects of self. The cortical mind, our top-down brain, likes to have something to do. To keep it from dominating the dancing scene, we can give it tasks. First, it can be helpful in setting up a schedule, getting us to the studio on time, and determining a regime. For example, a session might routinely begin with a body scan while moving, so all the body is awake. But creativity is rarely a linear process.

Whole-body thinking needs to take over. Both the agency body that moves us in space and the volume body that supports feelingful expression and gutsy connections can be called on to find pathways into movement. All the resources already explored in these chapters are available: orienting to weight and space through the bones, heat and range with the organs and muscles, and presence through the skin and senses. Sometimes music helps; at other times, the inner pulse is enough. Throughout, there is a cycling of awareness. Sensation permeates everything. That’s where dancing starts.

Once the process is familiar, any place, any time is for dancing. In an instant, we can arrive, access a creative state, and move. Completing the adventure, we return to daily life. The membranes are permeable between moving and dancing, the ordinary and extraordinary. We can notice when we are preparing to dance and when the dancing takes over and dances us. Some days, we can spend most of the time getting started, and other days, we are immediately present in a moving, dancing body. This is our place of dance—available for a lifetime, portable, practical, and free.

STORIES

Nurturing Creativity

A writer’s calendar depicts twelve female authors in their studios. One writes lying down in a cozy bed; another rents a room in a local motel for privacy; and another stands at a desk by a window. Each has a space and set of conditions that supports her process. What’s yours?

Finding Space

Some dance graduates say they don’t have time for class, can’t locate a studio or money. This too is a practice: finding time and space, and committing energy. In the first decade of our dance company, we did technique class daily—anywhere and everywhere. Pliés and tendus graced kitchens, balconies, and an empty ice cream parlor. On tour without a studio or stage, we simply found a space to move. Being resourceful is part of dancing, requiring both inner and outer endurance and creativity.

Being a Dancer

According to dancer David Dorfman, getting choreography done requires overcoming inertia: you get a core of dancers together, make a schedule, and develop material as a regular practice. He says, “A big percentage of being a choreographer is organizational—your long life of dance making is largely logistical.”

Photograph by Angela Jane Evancie

TO DO

Three Long Walks (Caryn McHose)

10 minutes

Three bony places in the body link back body with front body; when identified, they offer entranceways, landmarks linking your back body depth with forward body expression—moving you from thinking about a project to bringing it forth in the world.

Calcaneus

Standing in plumb line, bring your attention to your feet:

• Shift your weight toward your toes, your heels, and then circle the weight around the circumference of your feet. Close your eyes, circle your head, and notice the tiny adjustments of the twenty-six bones of your feet.

• Bring your attention back to your heel bone, the calcaneus. Feel or imagine the shape of this large bone directing the foot from the back.

• Refresh the long walk of the calcaneus, from back to front of the body.

Sit Bone to Pubic Bone

Seated on the floor or on a firm chair, bring your attention to your pelvis:

• Rock your weight forward and back, and feel the region between your “sit bones” and your pubic bone (the front of the pelvis). This region on each pelvic half is called the ramus—one of two feet of your pelvis.

• Notice if you can rock your weight on the “long walk” between your sit bones and pubic bones—the rami—and stay relaxed in your thigh muscles, separating leg from torso muscles.

• Continue rocking forward and backward, bringing stimulation to the full length of the rami: this long bone on each pelvic half makes a V to the front of the pelvis, like the prow of a ship. The right and left pubic bones connect at the interpubic disc, creating two joints at the front of the pelvis, one for each side.

• Option: you can also bring awareness to one ramus by lying on your side on the floor. Lift the top leg slightly so you can use your hand to trace the “long walk” from sit bone to pubic bone. Change sides. Notice how the bones meet in a V, creating an attachment site for the front triangle of the pelvic floor.

Occipital Condyles of the Skull

Seated or standing, lightly touch the outside flap of your ear that covers the hole (external auditory meatus):

• Imagine your fingertips on each side of the skull meeting in the middle of the head, creating a horizontal axis through the skull, linking ear to ear.

• Nod your head “yes,” and feel the place where the skull meets the top vertebra, the atlas. This one-to-two-inch-wide joint also connects from back to front of the plumb line in efficient alignment.

• Use your hand to feel the curve of the occipital bone, the back of the skull. The condyles are part of the occipital bone, in front of the hole of the spinal cord. The occipital bone is one of the three primary bones linking front to back in the body.

Integration and Differentiation

• Take a walk, feeling the spaciousness of these long walks, these three landmarks in your body. Notice if they increase your sensation of depth, front to back. We often think of our bodies as flat, from photographs and mirrors. But actually, depth is essential in dancing.

TO DANCE

Presentations—Building Duets (Paul Matteson)

30 minutes

Sometimes you get stuck moving in one place; presentations help you get started extending beyond your comfort zone.

Starting seated on the floor with a partner, touching back to back:

• Dancer A presents a limb in space (arm, head, shoulder, foot). Dancer B extends the presented line in space, using hands or other body part to create an energy line.

• Dancer A follows the extended line wherever it takes him or her until the energy resolves. Dancer B accompanies the journey.

• Dancer A presents another limb in a clear directional path. Dancer B extends the line or vector in space and follows through space.

• Stay alert: use strong enough touch to mobilize the presented limb without forcing, or overextending joints.

• Repeat for 5 minutes: presenting, extending, following, until it resolves.

• Change roles. Dancer B presents a limb; Dancer A extends a line (using hands or another body part) and follows it in space, using any body part to reach, any part to extend (5 minutes).

• Alternate presenting, extending the line, without talking. Stay in continuous motion (5 minutes).

• Explore dancing the duet with no one leading (5 minutes).

• Show your duets (5 minutes each).

• Construct set material from your experience, collaboratively building a short, choreographed duet. Retain the freshness of the improvised experience, while remembering landmarks.

• Show and discuss what you find.

PearsonWidrig DanceTheater

Photograph © Tom Caravaglia

TO WRITE

Creative Conditions

20 minutes

You’ve been thinking about your values and longing. Now go a step further. Describe your creative process. What works for you? Consider time, place, and useful stimuli. Identify one aspect of your process that could be more efficient or effective, and explore how that could manifest in your studio practice.

Photograph by Erik Borg, courtesy Middlebury College Archives

STUDIO NOTES

PENNY CAMPBELL leads a warm-up for a Performance Improvisation course at Middlebury College in Vermont (2007):

Dance begins in sensation. It starts with you.

Lying down, eyes closed:

• Begin each time where you actually are, how you feel in this moment, in this place. Notice sensation. Begin moving, finding impulses in your own body, however small or large.

• Don’t judge at this point. Be curious. Just follow the movement that emerges. Notice when you get those little sensations of “yes, this feels right” or “no, don’t want to go there.” Follow the “yes.”

• If you find yourself in familiar movement, look for new initiations, investigate possibilities. Change one little thing, just a little bit. Stop rather than go, go rather than stop, or change level.

• Feel your skin on the floor; gradually warm up through muscles; notice bone. Remember that movement comes from and creates sensation. Follow sensation.

• Return to your breathing; connect to your inner experience.

• Begin as a soloist. Root the whole process in you. Grow a deep root, a strong connection, so when you add vision and dance with others your choices are still sourced in you. Let things unfold moment by moment. If you lose that connection, close your eyes for a moment and reconnect; start again.

• Dancing can begin long before we are actually warmed up. It’s a state of mind, focused attention and intention. Notice when warming up becomes dancing.

• Change levels and explore new spatial orientation. Stay rooted. Don’t judge. Let the little ticker tape of self-criticism become background noise that you ignore. Return to sensation.

• Move each body part: from feet, to ankles, to lower legs, to knees, and on up through the body. Open through your shoulders. Find back-space. Continue moving. Be very specific (the left-nipple dance, the back-of-your-ear dance). Take your time.

• Try a duet with two body parts talking to each other.

• Make a different dance with each arm: find two voices. Feel your head and tail. Explore your spine. Find the articulation in each leg.

• Wake up all your senses: notice smell, sounds, and tastes as you move.

• Pick up speed. Go as fast as you can. Find unusual weight shifts. Surprise yourself. Really open your eyes now. Build your stamina. Go to your limit, and then continue three seconds longer. Develop your endurance.

• Use whatever happens (giggles, crashes). They are all material (keep your focus—don’t drop out). Don’t stereotype some movement as “dance” and exclude other movement (usually automatic movement) as “not-dance.” Everything is part of the unfolding event. All of it is compositional material. Deal with it.

• At some point, dance with each person in the room and with the room itself. Stay rooted in your own experience. Borrow movements and try them on. Catch a part of a movement, or be that person in the movement.

• Brush up against each person. Explore near and far. How close can you get? How far away can you get? What’s safe? How does it all feel?

• Use your eyes; follow your eyes in space. Let them lead you somewhere. Fix your vision in space, and move to and with it.

• Find your back-space; notice the space between body parts, between you and others.

• Expand awareness to the whole group, the whole room.

• Bring your movement to a close. Notice possible endings: how long does it take; what feels right in the moment? Find an ending that makes “sense.”