Читать книгу Body and Earth - Andrea Olsen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

We react, consciously or unconsciously, to the places where we live and work, in ways we scarcely notice or that are only now becoming known to us…. In short, the places where we spend our time affect the people we are and can become.

—Tony Hiss, The Experience of Place

Body and Earth is about relationship. It is a guide to help us reflect on what has shaped our attitudes and ideas about the world and about ourselves. Through our education in our homes, in schools, in our travels, and in our spiritual communities, we have developed a relationship to our bodies and to the environment. In this book, scientific views and experiential exercises are interwoven to help us investigate these attitudes and ideas, to notice if they are currently useful to our lives and to the health of the earth.1 With attention to how memory and new information interact, we can become aware of our biases and assumptions and stimulate our imagination and curiosity for further exploration.

HUNTING FOR HOPE

Environmental writer Scott Russell Sanders teils of a backpacking trip he took with his sixteen-year-old son. His numerous books and articles detail the changes in his Midwest landscape, the destruction ofecosystems, the carelessness of our relationship with the earth. At the end of a difficult climb, the son turned to his father and said, “Your writings are destroying my hope.” This comment inspired his next book, called Hunting for Hope.

The body is the medium through which we experience ourselves and the environment. The ways we gather and interpret sensory information affect both how we monitor our internal workings and how we construct our views of the world. Thus, the text begins by exploring underlying patterns and perception, including basic principles of life and earth sciences that have shaped and currently affect our views of both body and earth. Next, we focus on the weave of relationships between bones and soil, breath and air, muscles and animals, digestion and plants, water and fluids. The text concludes with animating aspects of body and earth, including sensuality, creativity, and spirituality. Thus, the book provides a context to revisit and revision what we know, by noticing patterns of interconnectedness.

Throughout this study you are invited to choose a “place” in nature near enough to home for consistent field study visits. With notebooks in hand, we attend to specifics of our environment in order to connect to the places we live as participants and inhabitants, rather than as passersby. Weather patterns and seasons help us notice natural cycles of change, experience death or transitional stages as part of life, and deepen our relationship to the rhythms of the natural world. The goal, as we heighten sensual awareness of the environment and track our perceptual biases, is to expand our ability to respond, our response-ability, and ultimately to recognize ourselves as active participants in the world.

Language is a map for a way of thinking. Recognizing that language can point toward but does not replace experience, I have attempted to present specific information to enhance our creative explorations. In this study we learn the names of things as a way of claiming intimacy. We see not simply “leg” but “femur;” not “bird” but “barred owl.” We use naming to suggest valuing through specificity. With a fresh view of language we can enhance our sense of familiarity, of family. Names reflect the universality as well as the uniqueness of each individual person, plant, or soil type. We are part of a larger group with shared characteristics, and we are also unique in each moment.

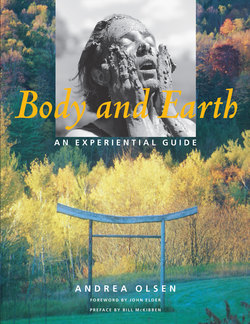

The art images, writing suggestions, and “to do” exercises in the book suggest forms for creative expression. They represent the life work of many individuāls filtered through my own experience, offering a brief introduction to much larger fields of inquiry. In many cases the primary source of an exercise has been obscured as, over time, information has been passed from teacher to teacher. By using these exercises to enhance awareness of body and earth, we honor a heritage much larger than ourselves. Multicultural images encourage a world perspective, children’s art refreshes, and illustrations clarify. Sometimes it takes many views to point toward truth.

Storytelling is included as an integrative process. The experience of reading, telling, and hearing stories can enhance our connection to people and to place. In many ways, storytelling transmits an experience so that listeners envision it for themselves. Re-creation in the form of storytelling is a kind of re-membering, assembling pieces to create a whole in which many dimensions can be experienced at once: emotions, ideas, facts, sensations. Within our bodies, a good story engages the limbic system of the brain, the area that registers interest and emotions, and engages memory.2 It’s the part of the mind that keeps one turning the page when reading a book. A good story touches all of us, brings us to the moment, not simply as observers but as participants.

When I ask students to write their history of place, many create eulogies for places that no longer exist. Even at twenty years of age, they see that the open field is now a parking lot, the favorite woods a subdivision, the family home long since departed. Writing about place is often writing about loss. We begin by recognizing our grief; we continue by celebrating connection to the places that shaped our lives.

Time is a considera tion for the journey through Body and Earth. The overview of thirty-one “days” or learning sessions can be approached as a month of exploration, a twelve-week course meeting three times a week, or a progression to do at your own pace, alone or with a group. No matter what time is set aside for study, we are cultivating timelessness. Some experiences take a lifetime to understand; others, a decade; some are integrated in a moment. Building this quality of timeless exploration into our lives in a conscious way, helps develop the sensibilities essential to humane and creative living.

Environmental studies students at my college are like the art students of the sixties. Energetic and hopeful, they feel they have a role to play in changing the world. And the results of the environmental focus are evident, changing the face and values of our college. Backpacks are everywhere; beards and hiking boots balance J. Crew; organic gardens and compost heaps replace overstuffed dumpsters; alert, lively senses counter the numbness of alcohol. We need reminders that change is possible and that each discipline, each person, has a role to play.

This book provokes an essential question: How best to live on this earth? By focusing on our human bodies as the vehicle through which we experience ourselves and the world around us, we learn to value the earth equally to the self. Thus, the perspective is both anthropocentric (human-centered) and ecocentric (earth-centered). The body and the earth are complex and profoundly interconnected entities developed through billions of years of evolutionary process. Our task is to develop a dialogue with this inherent intelligence—to learn to attend. By enhancing active awareness of our bodies and the places we live, we deepen our engagement in the intricate and delightful universe we inhabit.

What Body and Earth offers, simply, is a map to guide experience. In editing the text, I’ve attempted to honor the body’s capacity for absorption. In reading, one can only integrate what is relevant to the moment of attending. As writer, I offer what I can hold in one life, shared with friends like a good conversation. So when I had to choose what to include in a chapter, I would go outside and read aloud to the plants, go to the studio and speak as I moved, or go to the mountains and tell the story about water to the stream to see if it rang true. And that is what, finally, I offer to you in this experiential guide.

Preparation for using the text

Find an indoor space suitable for private work. A wood floor and natural light is ideal; the space should be warm and comfortable. Minimize distractions: unplug the phone, turn off the computer, remove your watch. Wear loose-fitting clothing; no shoes or socks. Have pencils and a journal or pad for your notes and drawings. Establish a realistic schedule; consistency of time and place helps calm the mind for focused exploration. You will also choose an outdoor place (See Day 1); each offers unique resources.

Drawing by Claire Crowley, age two.

My stepson’s seventh-grade math class focused on grapbs. The teacher began by taking a survey of what students “were most afraid of.” The final pie chart, colored in pale red, green, and blue, showed homelessness was the major fear for 60 per cent of these rural students, followed by war and divorce. They were facing the fear that there is no place on this earth to call home. How do we acknowledge that each of us has a place; that both our body and the earth are home?

“To Do” movement explorations

Read through (and tape-record yourself if possible) the entire “to do” section first, then begin. As you become familiar with the process, it will become easier to follow the instructions. When working with a partner or in a group, have one person read aloud; then change roles. Respect your own limitations; modify any exercise that does not feel comfortable to your body. Use a yoga pad, meditation cushion, pillow, or chair for support as necessary.

Use the margins in the book to record your experience. Note what actually happens—your feelings, sensations, and associations—so that you can observe your process over time: “I was distracted” or “I felt light and relaxed.”

Creative writing

Write from your whole body. Try to keep your pen moving, as you maintain a nonjudgmental attitude. Resist editing or censoring your words. The task is to let your body write you, that is, to become a vehicle through which your own stories emerge.

Read all of your writing aloud; include every word. When you read, both hear and feel your language. Often the experience of reading is different from writing. Cultivate a supportive listener within yourself. If emotions come, allow yourself to continue reading with the feelings. We need our whole self present in our words.

When giving feedback to others in a group, comment on what stands out for you, what moves you. Maintain your nonjudgmental but discerning mind.