Читать книгу Body and Earth - Andrea Olsen - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 1

Basic Concepts

We are not separate from the earth; we are as much a part of the planet as each cell in our bodies is a part of us.

—Mike Samuels, M.D., and Hal Zina Bennet, Well Body, Well Earth

We begin in wholeness. The interconnectedness of human life with the world around us is the subject of our study.

Body, in this text, refers to all aspects of what it means to be human. The parts may sometimes be referred to individually as soma, soul, spirit, psyche, physical body, emotional body, intuitive body, energy body, thinking body, mental body, or collectively as person, self, “I.” In our study, the word body is an inclusive term referring to the whole being.

Earth, in this text, refers to all aspects of our planet. The parts may sometimes be referred to individually as atmosphere, ecosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, geosphere, mantle, crust, core, or collectively as Gaia, globe, world. In our study, the word earth is an inclusive term referring to the whole planet. Body is an aspect of earth.

Place, in this text, refers to a particular part of the earth that we know through direct experience in the body. Relationship to place is a process of assimilation, without which there can be no understanding. It is through our interaction with specific landscapes and environments that our movement patterns, perceptual habits, and attitudes have been formed. As we reflect on the places that have shaped our lives, we recognize that body affects place and place affects body in a constant process of exchange.

Where we focus our attention affects what we perceive. In this text we attend to the body as the medium through which we experience the earth. At various points in our exploration, we must put down our books, quiet our words, and simply go outside. Participation is the connecting link to awareness. As we open our senses to the natural world, we can recognize the experience at hand as the primary resource for our learning.

CONNECTIONS

When I first taught a course called “Ecology and the Body,” a colleague met me at a department meeting with a stack of books and a typewritten note. The first sentence stated that ecology has nothing to do with the body. The note ended by saying that if there was no math in my course, it was not ecology. The Environmental Studies chairperson responded to my concerns with the reminder that scientists use language to be specific, writers to encourage association. Both are useful. He also quoted Rachel Carson: “You can’t write truthfully about the sea and leave out the poetry.”

Several weeks later a student reported a sign posted in a bathroom downtown: “Don’t flush, save the Ecology.” This helped me see the need for specificity in language; it also encouraged my sense of humor. Then, at a college-wide lecture, a distinguished environmentalist began his talk by announcing that every elementary student now knows that ecology means the interrelatedness of all living and non-living things. From my perspective, the human body is included.

Some students who protest the use of chemical spray on blueberry barrens in Maine, scorn pesticides and fertilizers in the grain fields of the Midwest, denounce pouring raw sewage into streams, and bemoan the cutting of trees in the rainforest, do not hesitate to take Ritalin—“vitamin R” (to stimulate brain chemistry so that they get their homework done), Paxil (to slow down or feel calmer), Motrin (for torn or overused muscles), or Valium (to get to sleep at night after too much coffee and too many hours of computer buzz).

What goes into the bloodstream enters the tissues, alters hormonal secretions, and affects the overall balance of the body. Why is interconnectedness important when talking about the migration patterns of the yellow rumped warbler but not the hormonal secretions of the thyroid gland; DDT threatening reproduction of the bald eagle because of thin shells on eggs but not the possible effect of Paxil on sexual function? We are odd creatures, we humans. We still don’t recognize that what is out there is in us, and what is in us is out there.

TO DO

Inner and outer awareness

10 minutes

Lying comfortably or seated, eyes closed:

• With each breath, feel or imagine the exchange between the outer environment of air around you and the inner environment of your body. The outer environment becomes part of the inner environment with each inhalation, and the inner environment releases to the outer environment with each exhalation.

• Gradually open your eyes. Notice whether you can remain aware of the sensations of breath while adding vision. This is the primary dialogue we will be engaged in throughout our work: the capacity to maintain inner awareness while attending to the outer world, a process of inclusive attention.*

Constructive rest

10 minutes

Lying on your back on the floor, in a warm, private place:

• Close your eyes.

• Bend your knees. Let your feet rest on the floor, slightly wider than your hips. Let your knees drop together to release your thigh muscles.

• Rest your arms comfortably on the floor, below shoulder height.

• Allow yourself to be supported by the floor.

• Allow your breath to move three-dimensionally in your torso.

• Allow the eyes to relax in their sockets, like pebbles dropping into a pool.

• Allow the brain to rest in the skull.

• Allow the shoulders to melt toward the earth.

• Allow the weight of the legs to drain into the hip sockets and feet.

• Allow the organs to release toward gravity.

• Allow your mouth to gently fall open; your tongue to relax.

• Feel the air move in and out through your lips and nose.

In constructive rest, rather than controlling your body, you let it be supported by the earth. As you release your body weight into gravity, the disks are less compressed and the spine begins to elongate. Constructive rest is an efficient position for body realignment. It releases tension and allows the skeleton and organs to rest, supported by the ground. Constructive rest is useful at any time of day but especially if done for five minutes before you sleep. The relaxation of the body parts returns the body to neutral alignment so that you don’t sleep with the tensions of the day. Constructive rest is discussed by Mabel Todd in her book The Thinking Body: A Study of the Balancing Forces of Dynamic Man.

* Inclusive attention is a term used by Susan Gallagher Borg, director of the Resonant Kinesiology Training Program.

Place map30 minutes

• Draw a map of a familiar place. Choose any place you have lived or visited that evokes strong feelings. Take time to fill in details and important landmarks. Consider pathways, boundaries, and orientation to light. Don’t worry about the process of drawing; use symbols to represent areas of specific memory or meaning. 10 min.

• Write about the map and/or the place you’ve drawn. 15 min. Read aloud to yourself or a small group. Breathe deeply as you read, allowing exchange between the inner landscape of body and the outer landscape of place. 5 min.

Place visit: Finding your place

• Find a new place outdoors that you can visit each day. Look for an area that you can enjoy, within walking distance from your home or workplace and private enough that you can visit consistently, undisturbed, for twenty minutes at a time, engaging inclusive attention. Follow the place visit with ten minutes of writing in your field journal. Remember to allow time for direct engagement with place before writing and reflection, valuing experience as well as the language used to describe it.

Standing amid a swarm of mosquitoes, my flyfisher neighbor in Maine addresses the principle of interconnectedness even more simply: “You can’t have the fish without the bugs.”

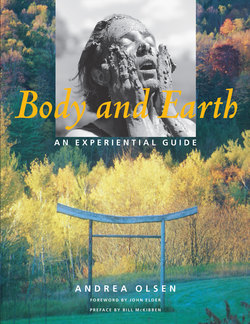

Quarry, New Haven, Vermont. Photograph by Erik Borg.

FARMSTORIES [1994]

We left the farm when I was twelve. I don’t remember the details of departure. There must have been weeks of packing and a moving van. There was a huge barn sale, I am told, and good-byes to friends and neighbors. I don’t remember anything. I don’t remember what happened to the thirteen cats who lived in the outbuildings and supervised the field mice or who took or killed the last of the grumpy laying hens whose eggs I had so diligently gathered through the years. I don’t remember the day that Rosebud, our five-gaited mare was driven away in the horse trailer or whether I kissed my best friend Cindy good-bye and promised to write and be friends forever. I don’t remember emptying my bedroom closet of its pile of discarded dolls, seeming angry or sad about no longer being loved; whether Huffer Puffer, our very stupid but lovable cocker spaniel was returned to his original owners; or who took the trunks of grandmother’s white dresses and linens that my mother had so carefully saved to pass on to her girls.

I don’t remember anything about the move except arriving at our new house on Park Place and sleeping in the same familiar bed. I vaguely remember arriving; meeting Judy, my new best friend; taking Traveler, our collie, for his first walk on a leash to the park at the end of the street. But I don’t remember saying good-bye to the fields, to the luscious cherry tree, which gave us fruit for jam, or to the garden where my mother grew zinnias and I came to know the fecund smell of overripe tomatoes. There was no farewell to the pump house where we stored our tadpoles; the deep cistern that we were not to fall into; the giant elm tree where the cicadas left their shells; the willow tree, which was our dollhouse; the outdoor stone fireplace where I prepared flower-petal soup for of all my imaginary children. Or the long flat view, which showed the horizon, and the houses of all of our friends and neighbors; and the line of dust warning that a car ten miles off was coming our way. I don’t remember saying good-bye to any of this, and it is with me still.

Read aloud, or write and read your own story about home.