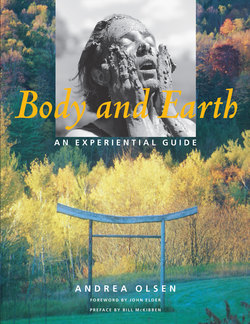

Читать книгу Body and Earth - Andrea Olsen - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 2

Attitudes

The failure to develop ecological literacy is a sin of omission and of commission. Not only are we failing to teach the basics about the earth and how it works, but we are in fact teaching a large amount of stuff that is simply wrong.

—David Orr, Ecological Literacy

Our attitudes inform our actions; the way we think affects what we do. One prominent view in Western culture is that nature is a “thing,” an object with utilitarian value to be bought and to be sold. With this consumerist focus, we may consider the empty field, the lake, or the mountaintop to be property, a storehouse of resources, or a challenging landscape to conquer or control.

Another view offers a radical alternative: that nature has intrinsic value in and of itself. We can experience the world around us as an organic living thing. It is not object but subject. It has interiority, subjectivity. It has something to teach us, and it inspires respect. When we have this attitude, the natural world can evoke awe and astonishment, stimulating connection to the sacred, integrative forces of life.

The same attitudinal values are prevalent about the body. One predominant view, perpetuated by our educational and medical habits, is that the body is an object, a machine to be repaired when it breaks down. It is our property to do with as we please. It is a resource to get us from here to there, a commodity to help us get what we want, a storehouse of resources, a challenge to control, to conquer or overcome.

Hayloft, painting by Philip Buller. Watercolor on paper, 22 in. × 33 in. Collection of J. Slovinsky.

VIEWS

Many students want to “gain control” over their bodies. I have to remind them that this is not our goal. The task is to learn to listen to the intelligence of our home. When we value what the body has to tell us, we create a dialogue with our senses. The same is true for the earth. The task is to develop a relationship with the details and cycles of life around us. In this way, we are participants in a larger story. Control limits possibilities; dialogue invites surprise.

A young psychology major wrote of her childhood close to forests and rivers and her years of caretaking the land. Then she said, “You know, I treat the environment much better than I treat myself.” An athlete remarked, “This is a new experience for me; I’ve been abusing my body all of my life.” A student from Manhattan said, “I realize that I am most comfortable in rural Middlebury when I am near the highway. I need to hear traffic to fall asleep.” As we listen to our bodies, we hear the stories of our lives.

The only time my life has been threatened was when living at a wildlife sanctuary. In that protective environment, our bluebird boxes were regularly smashed, and my husband was chased by men with baseball bats because of our assumed role in restricting land use. One young man in particular considered any “environmentalist” fair game for harassment. On my afternoon walk in the neighboring countryside, he would drive his pickup truck as close as he could, making me jump off the road. After a few weeks of intimidation, I decided to stand my ground. As he sped in my direction, I stood in the middle of the road, waving both arms for him to stop so that we could talk face to face. I leapt to the side just as he rushed past. I could have died. Being considered a spokesperson for the earth puts your life on the line; not speaking up threatens life as well.

Our neighbor tells of visiting a professor of ornithology for help in identifying a bird. The teacher responded, “Wouldn’t you also like to know something about how it lives its life?” A bell went off in his mind: there is more to identification than naming. It’s the matrix of relationships with the world that gives us insight into another species, not just its label.

The radical alternative in body attitude would be that the body has intrinsic value in itself. It has interiority, subjectivity. It has much to teach us if we learn to listen. We can consider that we are part of a vast interconnected system, rather than separate from the world around us. We are nature too.

As we recognize our interconnectedness with the rest of the earth, we begin to see the world from a relational perspective, supported by our context rather than in isolation or at odds with it. We experience the air, the water, the soil, the animals, the people around us, and our own bodies as familiar. In this view, both body and earth are home.

Underlying the environmental crisis is a crisis of attitude. We are coming to the end of our nonrenewable resources, such as fossil fuels. We are also coming to the end of renewable ones, such as clean water, clean air, and healthy soil. This is true of the body as well. We can no longer count on resiliency in our structure: our bodies are too busy recovering, attempting to filter internal as well as external toxins. Yet we can consciously cleanse our systems and balance our energy, just as we can protect the resources around us. Our attitudes toward our bodies have everything to do with the health of the earth.

As we open our senses and attend to the earth, we encounter grief. Emotional memory is encoded since childhood, associated with specific terrain: the beach explored on family vacations, the tree climbed in moments of retreat, or the room where a child was born. All too frequently, loved ones are gone, places paved over—in reality or in our hearts. Earth systems, too, are dying. Forests, songbirds, and the air in our lungs are in trouble.

Grief is a natural response to loss. Engaging our grief requires softening our guard. The process includes several essential stages: acknowledging our denial, allowing emotion, accepting death as part of life, and expressing through creative forming—giving voice to the forceful feelings that occur. Our attitudes toward our grief affect our ability to feel and to act.

Environmental Studies is one of the fastest growing majors at universities across the country. Alternative health care is a growing force that challenges traditional medical practices to include a holistic view of the body. Books, magazines, and art reflect environmental perspectives and healthful incentives. There is no discipline, institution, or individual exempt from environmental concern and responsibility. As we become aware of our underlying attitudes toward our bodies and toward the places we call home, we experience the dynamics of living an interconnected life.

Any integrative experience is a spiritual experience, humanist John Dewey reminds us. One component of mystical or spiritual involvement that underlies ecological concerns is the feeling of being an integrated part of the whole planet. Aesthetic experience nurtures this sensibility in people. Thus, the arts have an essential role to play in encouraging us to face the unprecedented challenges of our time.

Our attitudes can be affected by information, inspiration, or direct experience. We can learn how a lake is polluted by reading the newspaper, seeing a painting, or finding a dying loon on the shore. Each instance connects person to place in a moment of alertness.

As we envision life, we create it. As we think, we do. Experiencing ourselves as participants, we foster attitudes in ourselves and in our communities that allow a lively and respectful dialogue between body and earth.

TO DO

Body map 30 minutes

• Draw a map of your body. Start with an outline and fill in the details. Include what you know and what you feel: anatomical information, ideas, emotional connections, colors, images, injuries, words, intuitions, memories. Follow whatever captures your imagination. 10 min.

• Now fill in the context around your body—the environment. 10 min.

• Write about your experience. Read aloud. Pause at the end of each sentence or phrase, and take a full breath—inhalation and exhalation. Allow a final breath cycle at the end of the story. 10 min.

With a group:

Using a large roll of wide paper, cut body-length pieces. In partners, one person lies on the sheet of paper with eyes closed; the partner takes a crayon or marking pen and traces around the outside of the body, in one long continuous line. Change roles. 10 min.

• Take the outline of your body and fill in the contents. Consider context, outside the outline, as well. 10 min.

• Write about your experience. Read aloud to your partner. 10 min.

Breathing spot (Child’s Pose)5 minutes

In constructive rest: Roll to your side, flex your arms and legs close to the body and continue to roll to a “deep fold” position: limbs folded, chest resting on thighs, knees spread slightly for comfort, forehead on the floor, spine curved.

• Rest the warm palms of your hands on your lower back, between pelvis and ribs. Through touch, encourage the movement of skin and muscles in this area as you breathe. On the in breath, your diaphragm is pulled down toward the pelvis, compressing the organs and expanding the back surface of the body as your lungs fill with air; on the out breath, the diaphragm releases (toward the fourth and fifth ribs) and the muscles soften. We call this area of your lower back your “breathing spot.” Encourage its movement with each breath. As breathing deepens, invite sensation to travel all the way down your spine, and spread into your buttocks and legs; then up to the heart, spreading to shoulders, neck, and skull.

In yoga, this is called Balasana, Child’s Pose. Imagine a soft, rounded spine, responding to each breath. If you hold tension in your lower back, this is an excellent exercise to increase circulation and lengthen muscles.

Yoga: Child’s Pose, Balasana.

To write: Place story2–4 hours

Write your history of place, using a chronological approach. Include all the places you have lived and visited. Consider home, travels, dreams, and longings. Reflect on the place-origins of your ancestors. Notice the ways your place history has affected your movement and your attitudes: did you grow up by water, near forests, or surrounded by city streets? How does place affect your life today?

FARMSTORIES: MODELS—THE TRAVELER

My mother was a traveler. She was always at ease with the wealthy. In 1939, after two years of college and before her first teaching position, she took “the grand tour of Europe” collecting the ideas and objects that were to fill my childhood. She sailed across the Atlantic, arriving in England, then in Africa, traveling on the Continent, encountering Mussolini, turning around, and heading for home.

On the farm, this heritage of world adventure was transmitted to us by the Della Robia Madonna and Child porcelain plate hanging over our kitchen doorway, by the leather gloves and amethyst ring from the Ponte Vecchio in Florence; the carved-ivory Coloseum on the bedstand; the transparent blouses embroidered by women in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia; the woven vests and skirts from Norway.

Each of these objects, however small, was to detail a path that would make me a traveler. And so, in my twenties, when I began my own journeys, I walked under the smiling Madonna, wearing a transparent blouse embroidered by women who knew that life is how we embellish it, that’s all we get. That life is the body. That’s how we see it, smell it, taste it, and love in it.

Read aloud or write and read your own story about attitudes.

Place visit: Body scan

Lying in constructive rest or seated comfortably, with a vertical spine and eyes closed, begin a body scan. Pass your attention part by part through the body, beginning with your face and skull. Notice any sensation that occurs on this part of your body. It might be an itch, a tingling, or the pressure of your body against the ground. Move your awareness to your neck. Notice any sensation on your neck at this moment in time: the touch of air to skin, heat or coolness. (Repetition of language helps to focus attention.) If you feel no sensation on an area, notice that, nonjudgmentally. Sensations are happening all the time, whether we are aware of them or not. Move your attention through every body part: the back surface of your body, front surface, sides, pelvis, each arm and each leg. Remember, if you feel nothing, just wait, inviting awareness; then move on. Finish by observing breath as it falls in and out of your nose and mouth, moving the ribs, muscles, and skin. Open your eyes, remaining aware of sensation. Is your attitude toward place affected by deepening attention to body? 20 min. Write about your experience. 10 min.

Body scanning helps to develop an equal relationship to all parts of the body, with no hierarchies or areas of avoidance. It is a component of Vipassana Meditation, a Buddhist practice also known as insight meditation.

Photograph by Erik Borg.