Читать книгу Body and Earth - Andrea Olsen - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 4

Underlying Patterns: The Upright Stance

Our senses, after all, were developed to function at foot speeds, and the transition from foot travel to motor travel, in terms of evolutionary time, has been abrupt.

—Wendell Berry, An Entrance to the Woods

Bipedal alignment is our two-footed stance, a high center of gravity over a small base of support. As our vertical axis constantly sways over our feet, reflexive contraction of the muscles of the lower legs keeps us on balance. A subtle shift past the base initiates walking, striding, or running. In effect, we are constantly falling; instability is basic to our structure. Walking, arms swinging freely by our sides, is an underlying rhythm of our species.

In the evolutionary story, our quadripedal mammalian forebears emerged during the Age of Reptiles, around 180 million years ago. For these small, ground-dwelling insectivores and herbivores, larger carnivorous animals made life threatening. Some species moved to the trees and adapted to a posture of hunkering on branches. In this squatting position, feet grasped the branch and legs were folded (flexed) to the belly, leaving the hands or forepaws free for eating, grooming, and gesturing. The hunkering posture encouraged structural changes in the body: the heel bone (calcaneus) migrated to the back surface opposite the toes, an arch was formed by the connecting bones of the foot, and the pelvis shortened to allow the femurs to fold in squatting position.

The new use of the hands also developed a cross-pattern of thumb opposite fingers for grasping. Picking the plentiful nuts and flowers of the evolving seed-bearing plants (angiosperms) required coordination of eyes with hands. Our ape ancestors began hanging from their arms and swinging from limb to limb through the treetops, called brachiation. This allowed extension of hip and shoulder joints, repositioning of the shoulder bones (scapulae) to the back surface of the body for hanging and lateral reaching, contralateral rotation at the waist necessary for swinging, and elongation of the spinal curves. The curve in the lower back (our lumbar spine) formed last, after the arboreal swinger returned to the ground as a semi-quadruped. The transition then to upright posture was accompanied by the anterior (forward) curve of the lumbar segment. These characteristics prepared the way for two-footed, vertical posture: a bipedal stance.

Multidimensional agility of body and brain evolved simultaneously in our structure. Without moving our feet, humans can reach in front, to the sides, or behind. This three-dimensional rotation of the spine and hips permitted quick response in any direction. The free-swinging pelvis held the organs in a lightweight bowl and allowed mobility (unlike our close relative, the gorilla, who evolved from a common ancestor but whose large pelvis restricts vertical extension and whose knuckle walking and vegetarian diet encourage a more passive existence). The use of tools and the development of family groups increased the need for articulation and communication. In essence, we could stand, move three-dimensionally, manipulate our environment, and articulate with gesture and sound. Neurological adaptability increased our ancestors’ potential for survival.1

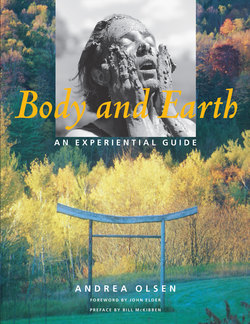

Nancy Stark Smith and Andrew Harwood. Photograph by Bill Arnold.

STANDING UP

“The Small Dance” is a movement exercise developed by dancer Steve Paxton. You close your eyes and stand with your weight balanced in vertical alignment. The intent is to notice all that is happening inside in what we call stillness: the myriad shifts, micromovements, rhythms, and idiosyncrasies that happen moment by moment. The small dance is our dialogue with gravity and the dynamics of the earth. As we open our eyes, we can remain aware of this conversation and “listen in” throughout the day as we stand in a line, talk on the phone, or walk through the woods.

Three body weights with horizontal diaphragms.

The basic characteristic of our species, Homo sapiens (wise man), is the increased capacity of the brain. As all of our systems developed simultaneously with our skeletal-muscular changes, our physiological capabilities were matched by our capacity for three-dimensional thought in the past, present, and future. (Imagine our brain in the body of a horse.) We are able to reflect on where we have been, contemplate where we are, and plan where we are going. This capacity for reflection, planning, and manipulation of our environment brings the responsibility of choice. Our ability to plan and to shape our environment makes us responsible for what we create and for how we choose to live in that creation. As we reflect on the precarious stance of the human—center of gravity vertically balanced over the length of our feet, constantly falling, essentially alert—we recognize that responsiveness and responsibility underlie our relationship to the earth.

The evolutionary progression to verticality offered additional implications for our bodies. As three primary tissue layers differentiate in the developing embryo, the ectoderm becomes the skin and nervous system, responsible for communication; the mesoderm becomes the skeleton, muscle, and connective tissue, responsible for support; and the endoderm becomes the organs, essential for breathing, digestion, and reproduction. In a simplified drawing of the bilateral fish body, the brain and nervous system are on the top for perception and communication, the segmented skeleton is next for support, and the organs hang by connective tissue (mesentery) off the spine for metabolism and reproduction, creating an efficient layering in horizontal alignment.

Shifting these layers into human verticality alters our dialogue with gravity. What used to be horizontal support (i.e., our backs) is now a vertical series of balanced curves. What used to hang (our organs) is now stacked. What used to communicate (our spinal cord and brain) is now an axis integrating head and tail, sky and earth. Our genitals, belly, breasts, and face, once protected by their horizontal relationship with the earth, are exposed, creating a vulnerable but dynamic and expressive body. Communication within community is now face to face, belly to belly, responding to information from all the senses.

In the core of the body, several musculotendinous partitions, called diaphragms offer horizontal support in vertical alignment. Beginning with the skull, the cranial diaphragm creates a sling for the brain, cushioning it from impact as we walk. In the neck, a vocal diaphragm supports the structures for voice. In the torso, the thoracic diaphragm creates a mobile rhythmic floor for the lungs and heart and massages the organs during the process of breathing. The pelvic bowl includes a fibrous pelvic floor, offering resilient support for digestive and reproductive viscera. Even the arch in the foot, a webbing of muscles, tendons, and ligaments below the bony bridge of tarsal and metatarsal bones, creates a horizontal diaphragm, offering spring and shock absorption for our striding gait.

Along with the vertical axis supporting bipedal directionality, human structure includes three globes (skull, ribs, and pelvis) and four rotary joints of shoulders and hips through which we occupy spherical space. Although we often think of ourselves as flat and two-dimensional, as reflected in photographs, mirrors, and on television or computer screens, we have sculpted fullness. Curves and angles give force and agility to the body, connecting us with forms beyond and inside us. Nerves inform us about the landscape, interior and exterior. The human form inhabits spherical space, as multidimensional and diverse as our curiosity allows, inviting investigation and discovery.

In an efficient vertical stance, the skull, thorax, and pelvis are balanced around an imaginary plumb line or vertical axis. If we draw three ovals, representing these three body weights, and connect them with a vertical plumb from the top of the skull to the feet, we have a diagram of postural alignment in the body. The front is also called the anterior or ventral surface, and the back is the posterior or dorsal surface, as we look at the body from a lateral, or side, view. The three body weights connect with a series of reversing curves: anterior at the neck, posterior at the ribs, anterior at the lower back, posterior at the pelvis (sacrum), and anterior at the small curve of the coccyx—the ancestral tail—connecting to the front surface of the body through the webbing of the pelvic floor. Each spinal curve touches but does not pass the plumb line in front. The center of gravity lies in the area behind the belly button at the front of the (lumbar) spine, intersecting the plumb line. To locate the center of gravity (c.g.) in your own body, imagine the point created by the intersection of the three primary planes of the body dividing you equally by weight: front to back, side to side, top to bottom. The c.g. is in front of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra in most bodies.

Additional bony landmarks for efficient postural alignment include the two “feet” of the skull (occipital condyles) as they pass the entire weight of the structure (some 13–20 pounds) to the first vertebra of the spine (the atlas). The ischial tuberosities (sit bones) are the two “feet” of the pelvis, which point straight down in efficient postural alignment, standing or seated. Balanced alignment of the pelvic bowl requires that the front rim of the pelvis (pubic bone) support the organs. Imagine that the entire front surface of the body—pubic bone, belly button, sternum, and nose—has an upward energy flow, and the entire back surface of the body—back of skull, back of ribs, and back of sacrum—has a downward energy flow (like a waterfall), creating a cyclical pattern throughout the structure. The two body surfaces—anterior and posterior—complement and run parallel to the imaginary plumb line, or central axis.

When our bones are balanced in efficient alignment, we feel less. In fact, with minimal feedback in the nervous system, we may feel as though we aren’t doing enough. People move to feel themselves working. But no sensation is the sensation of ease. As weight passes toward gravity through the bones, there is levity in the soft tissues, an upward release. Balancing the bones removes compression on other systems. Our spinal cord and nerves remain free for receiving and expressing; the digestive organs, lungs, and heart can function effectively, maintaining homeostasis in the body.

Three body weights with spinal curves and landmarks for postural alignment.

When my father was dying, I visited ancestral homelands: Samso island off Denmark. Standing in a cemetery filled with headstones marked Olsen, I felt myself amid family. Less than two centuries earlier, someone departed this land to plant roots in America; someone stayed behind to till familiar soil. Now, we share a common history of place. Bicycling amid rolling hills surrounded by sea, I realized that the adjectives depicting this landscape were those I had heard, for years, describing my dancing: lyric, gentle, remote. I felt as though this place-heritage inhabits my body, informing the way I stand, speak, stroke my hand through my hair, even though I had never been here before.

I notice that many Environmental Studies students assume a similar posture: the “ES slouch.” Head slightly forward, ribs retreated, the spine is a waterfall of responsive curves, relying on soft tissue support. From carrying frame packs and portaging canoes or from assuming a receptive demeanor, this stance eventually hurts. We begin with the feet, aligning hips, ribs, and skull over this small base of support. Stacking the body weights engages the efficiency of the skeletal structure and allows weight to lever through the bones. The new stance can feel bold, evoking the potential of a balanced body.

“I can’t stand like this,” my students say. “it feels too direct.” “Not all the time,” I offer, “but know how to find your full height. Pass through it a few times each day; notice how people respond. There are situations when you’ll need to stand up for what you believe!” The next step is to practice speaking from this mobile and stabile place. Most of us squirm, shift our feet, avert our eyes. It’s not easy to be exposed to the simplicity of who we are and to acknowledge who we are capable of becoming.

Alignment is relationship, to self and the environment. Even when standing “still,” the earth is always moving, we are always moving. A gift of our bipedal structure is our multidimensional agility of body and mind, which keeps us alert and responsive, adaptable to change. The risk is that instability can cause fear and rigidity in our attitudes and stance. When we have a relaxed, toned body, if we are pushed, we recover. If we are pushed when rigid, we fall off center. Our fluid body, undulating spine, and reflexes of face, gesture, and language support our vertical and vulnerable selves.

TO DO

Postural alignment (Mountain Pose)5 minutes

Standing in plumb line, eyes closed:

• Touch the bump on the outside of one ankle. This is your outer malleolus, the lower end of the leg bone and the first landmark in postural alignment.

• Touch the large knob on the side of your upper leg bone (the part that touches the floor when you are lying on your side). This is called the greater trochanter the second landmark in postural alignment. Line the greater trochanter directly over the center of your ankle.

• Touch the center side of your ribcage, the third landmark in postural alignment. Line it directly over the greater trochanter and outer malleolus.

• Touch the center of your ear, the top landmark in postural alignment. Lift your elbows to the side and imagine lines from each pointer finger meeting in the center of your skull. Do a small “yes” nod around this horizontal axis. Line this joint up with the other landmarks for postural alignment.

• Touch the top of your skull and imagine the plumb line extending upward and downward, creating a vertical energy line around which the body parts are organized. This is called “extended proprioception” (imagined sensation).

• Check that the knees are not locked; weight should pass through the center side of each knee joint.

• From postural alignment, slide into your favorite “hang out” posture; feel this position. Then, beginning with the feet (your connection to the earth) slowly reorient your body toward postural alignment. Repeat.

• Sometimes it is helpful to use a mirror to “check” alignment. Stand with your side to the mirror; align the body, feet to head; then rotate the skull to look in the mirror and notice the vertical relationship of body parts.

• In efficient alignment, weight passes through the bones, your mineral body, to the earth.

In yoga, the vertical stance is called Tadasana, Mountain Pose. Imagine a favorite mountain as you stand, allowing its qualities to inform your body.

Spinal undulations (standing)5 minutes

Standing in postural alignment:

• Begin a spinal undulation from side to side, a “fish swish.” Imagine a mouth and eyes on the top of your head, a fish tail at the end of your spine, like a trout or shark.

• Swing your tail (pelvis) side to side to propel the spine and head, or swim the head through the water to lead the spine and tail. Keep the movement side to side, as though your front and back surfaces are between two flat panes of glass. This fish pattern, evolving 400 million years ago, still lives in your spine.

• Change to a spinal undulation front to back. Still imagine the mouth and eyes on the top of the head, but now you have a flat tail, like a whale or dolphin. This mammalian pattern, appearing 180 million years ago, still underlies your movement.

• Change to a spiral pattern of the spine, unique to humans. Begin rotating the pelvis and allow all the vertebrae to respond, like a flag wrapping around a flagpole. Let the eyes finish the spiral, looking behind you as you twist. This pattern was present in your earliest hominid ancestors in Africa 5 million years ago, and underlies your multidimensional agility—the capacity to move in any direction with ease.

• Reverse the spiral until you have a full swing, wrapping left, wrapping right. Include the whole spine.

• Repeat each undulation, noticing any place there is holding in the body: the neck, the heart area, the lower back or tail. Encourage mobility of the spine in all three directions to support the stability of your vertical stance.

Photograph by Erik Borg.

Three body weights with spinal depth.

Place visit: Attention to bipedal alignment

Begin standing in plumb line, eyes open: Look at the trees and plants around you from this vertical stance; imagine you are growing roots from your feet into the soil, intersecting with those of the plants at your place. Remember that the root system of a tree is often as large as its crown. Try spinal undulations standing; notice the mobility under your bipedal stance. Pause and observe place in open attention. 20 min. Write about your experience. 10 min.

FARMSTORIES: ARRIVING

When my parents were young, they decided to pull a long green trailer across the United States in search of a place to call their home, raise their children, lead a good life. They had passed through thirty-nine states and were headed toward California, when they found themselves parked next to the Grand Canyon with both children crying, “We want to go home.” So they turned the long green trailer around and headed back to Illinois, to the farm my mother’s father had given her as a present. He never expected her to live there.

When they arrived, they parked the trailer in the back pasture, under the black walnut tree, and set to work. Farming was familiar. Things were done just about the same as when my father’s father had tilled the soil in Denmark. When we left nine years later, everything had changed. We had entered the era of more: more land, more money, more equipment. And of less: less community, less intimacy, less humor. But a photo of this first season shows my parents standing side by side in a field of corn, children by their sides, watching the sun set on the horizon. This was their place, their work, their time to learn and grow together with the land.

Standing, read aloud or write and read your own story about the upright stance.