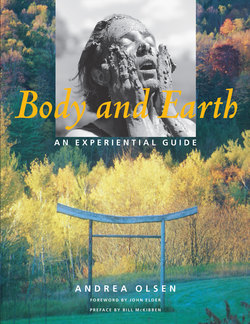

Читать книгу Body and Earth - Andrea Olsen - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY 6

Underlying Patterns: A Bioregional Approach

Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other…. What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value.

—Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience

A bioregional approach merges nature and culture; humans are considered part of, rather than separate from, the natural world. A bioregion is generally defined as an area with biological integrity, including all interacting life forms. Environmental educator John Elder elaborates, describing a bioregion as a naturally defined landscape, comprehensive in both topographical and biological ways and also in the way it includes human culture. The resulting permeable boundaries may have little relationship to political borders and can be viewed on various scales from local to global. Dynamic edge zones, called ecotones, result where one bioregion overlaps another, creating particularly rich habitats that support life from both regions.

To know your bioregion, it is useful to identify specific characteristics used to determine bioregional boundaries. We begin with a geological overview, reflecting the movement of tectonic plates and the volcanic and glacial activity that has shaped the terrain and waterways, influencing soil types. We also consider the resulting changes in climatic and atmospheric conditions, such as temperature and weather patterns. We then look at plants and animals, flora and fauna, and the ways they have altered with the arrival of humans. We reflect on the first Paleo-Indians, later migrations, and population centers. As we study agriculture, forestation, and industrialization practices, we can also consider prevailing religious, scientific, and cultural attitudes that affect stewardship of place. In other words, we look at soil and landforms, air, water, plants, and animals, including humans.

Canoe by Stephen Keith. Photograph copyright© Benjamin Mendlowitz.

NATURE AND CULTURE

My dance studio at the college has one wall of Vermont granite—metamorphosed limestone from warm, ancient seas. The floor is maple, cut in Vermont forests; the light-hued ceiling is pine. The piano, with its ebony veneer, reflects distant lands. I am aware at every moment of all that supports the body, gesture by gesture. Zen centers in Japan were modeled from ancient barns; this room reflects both. The dark-stained floor reminds us of simplicity, encourages us to touch our foreheads to the earth again and again. Conversing in this space, I ask a dance student what part of the country she might choose for graduate studies. She responds that place is not important. But I disagree. The landscape shapes who we are and whom we will become. These rooms, these floors, the mountainous horizon through the window are now part of everything she does. Each swoop of her arm holds a history of this room where we stand.

Barn reconstruction for Bramble Hill Farm, Amherst, Massachusetts. Frame isometric by Tris Metcalfe, architect.

For practice in developing a bioregional perspective we will focus on Middlebury, Vermont, the home landscape of this text. Middlebury is part of the Champlain bioregion, one of six major regions in Vermont. Flanked on the west and east by the Adirondack Mountains and Green Mountains, respectively, the town is nestled in the fertile Champlain lowlands adjacent to nearby Lake Champlain, giving this area a four-weeks-longer growing season than that of the mountains of southern Vermont. The Champlain bioregion is part of the larger Greater Laurentian bioregion, which includes most of New England and extends north into Canada.

Geological history shaped the patterns that contour our contemporary landscape.1 The Grenville orogeny is considered the first major mountain-building era of the Appalachian chain, occurring 1.3 to 1.1 billion years ago (bya). Geological records suggest that the oceanic crust bordering the eastern coast of a much smaller North American continent slid into the earth’s interior, in a process called subduction. As the continental plates, moving with convection currents from the planet’s internal heat, slowly collided, they created a lofty mountain range (comparable in height to the Himalayas)—the ancestral Adirondacks, which covered New York and Vermont.

You can touch rocks from the Grenville era today in the spine of the southern Green Mountains (Killington and Pico peaks) and the basement layer of the Adirondacks, although the mountains themselves gradually eroded and disappeared over hundreds of millions of years. The still-jagged Adirondack Mountains visible today are thought to have been formed from a geological “hot spot,” erupting under the crust around 2 million years ago and followed by erosion. Thus, they are considered “young” mountains in geological time.

Around 590–550 million years ago, Vermont was near the equator, partially submerged under tropical waters, with a hot and steamy climate. No flora or fauna had yet moved onto land. Three collisions between the North American plate and the African plate occurred between 590 and 250 million years ago, shaping and reshaping the land and endowing this bioregion with its present contours.2 The first collision, known as the Taconic orogeny, occurred around 450 (470–450) million years ago. Convection currents in the earth’s mantle reversed and began to close the proto-Atlantic Ocean, causing an underthrusting of the coastal slab. Shoving coastal rock inland, the collision upfolded another majestic north-south-trending mountain range, now called the Berkshire Hills and Taconic Mountains. This period created most of the dominant mountains in Vermont.

The second collision, the Acadian orogeny, occurred around 400 (450–345) million years ago, as land masses again collided, refolding the Green Mountains. A part of the crust from the proto-Africa plate, which had rafted out through the oceanic crust and had formed a micro-continent called Avalon, eventually collided with proto-North America.3 After the collision, as convection currents reversed, the continents separated and this part of Africa was left behind, newly attached to Vermont. If this geologic story is correct, New Hampshire and eastern New England were once African soil. Around 320 (345–280) million years ago, the final collision between the North American and African plates resulted in the Alleghenian orogeny, primarily affecting the formation of the Appalachian Mountains in the southern United States. Together, these mountain-building events—the Grenville, Taconian, Acadian, and Alleghenian orogenies—formed the Appalachian chain, extending from Quebec to Georgia. The elegant peaks were ground down by erosion and glaciation into the landscape we know, including the pastoral contours of the 350-million-year-old Green Mountains of Vermont.

By the end of the Alleghenian orogeny, around 250 million years ago, the supercontinent Pangaea had formed: a giant picture puzzle of continents with Vermont at its center, still near the equator. Broadleaf forests now covered the land and reptiles were abundant, including a plethora of giant dinosaurs. In the New England region, fossil remains show that three-toed dinosaurs strolled along what is now the Connecticut River; two-foot-long crocodiles that walked on four long legs and galloped with all four feet off the ground at once, left their 212-million-year-old fossilized remains in both Connecticut and Scotland.4 Pangaea itself was encircled by a giant ocean, Panthalassa, filled with burgeoning life forms, including sharks and sea turtles—successful species that continue today.

When the supercontinent began to break up around 200 million years ago, the Continental plates slowly drifted on convection currents to their locations around the globe, entailing significant changes in climate and in flora and fauna. The North American plate came to rest in the Northern Hemisphere, and Vermont developed a near-Arctic climate and a barren tundralike landscape. Dinosaurs were widespread on every continent and in many vārieties. Mammals began to appear around 180 million years ago, identified by fossil remains with small, shrew-sized jaws found in the western United States, Europe, and South Africa. Angiosperms dominated plant life, with flowers and seeds providing plentiful food. Mammals radiated, helping to pollinate and transport seeds in symbiotic proliferation.

The Ice Age began in North America around 2 million years ago, perhaps as a result of a collision with a meteorite, and ended as recently as 10,000 years ago. Four different glaciers descended from the north, repeatedly scouring the land, sculpting valleys, removing topsoil, and shoving the earth ahead of them as they traveled. The last, the Wisconsin Glaciation, encompassed all of New England in a one-mile-thick ice sheet, covering even the high peaks of the Adirondacks.

As the climate warmed, the ice sheet began to melt and retreat northward. Glacial residue includes piles of rocks and sand (terminal moraines); north-south scratches in granite bedrock from the moving ice (striae); and giant boulders (glacial erratics) that now sit amid farmers’ fields and in local forests. Glacial potholes and lakes reveal indentations in rock and soil from the massive weight.

“My family is in business,” a student said. “I came to school to be an economics major; my goal is to make money. Someday if the environment is really bad, I’ll be able to live where there’s clean air, clean water.” And he continued, “That’s why I came to school in Vermont, where the environment is still pure.” When we studied air, he recognized that the prevailing winds in our region of Vermont often blow in from the Midwest, bringing pollution from the factories in Cleveland and beyond; tree rings show nuclear fallout from tests in New Mexico; Vermont has serious problems with acid rain; and the state has one of the highest breast cancer rates in the country. He began to realize that there is no place on earth where money can protect you against pollution. The world is interconnected in such subtle ways that we must each attend to the whole.

When I teach yoga, we stand in Tadasana, Mountain Pose. The room grows silent. We feel bodies erect, weight dropping down, mineral bone meeting mineral earth. Eyes focus past the windows at the Green Mountains nearby, 350 million years old. Inner gaze connects to the skeletal core of our bodies. The breath is full, so all surfaces of the skin move as one. Time slows down.

The melting ice sheet traveled as far north as Burlington, Vermont, damming the northern drainage and spreading a giant Lake Vermont over its compressed roadbed. The lake was more extensive than today, and telltale markings of water levels can be found along the sides of cliffs and near the edges of the Adirondacks. The tops of nearby mountains (including Snake Mountain and Mount Philo), were tiny islands amid a vast waterway.

As the ice continued to move northward, the St. Lawrence River linked Lake Vermont to the Atlantic Ocean. Salt water flowed in, forming a shallow inland sea. Whale and seal bones, fossilized and found in Charlotte, Vermont, are dated from 10,000 years ago. As silt at the delta and the gradual rebound of the earth closed the northern outlet, the connection to the sea was lost, and the waterway once again became a lake. Freshwater Lake Champlain was much larger than its current size, with a rich, fertile valley to the east. The Champlain lowlands today feature a nutrient-rich soil of clay and silt from this time.

Many waterways in Vermont follow the northward path of the retreating glaciers. Lake Champlain itself, 125 miles in length, is sometimes referred to as the sixth Great Lake; it flows north to the Richelieu River in Canada, then to the St. Lawrence River and to the sea. Most rivers that flow into Lake Champlain, such as the Otter Creek, Lamoille, and Missisquoi, flow north, as does the Mad River further east.5 The Connecticut River, forming the eastern border of Vermont, is an exception. This 407-mile-long river has its headwaters in small lakes of northern New Hampshire and travels south to meet the ocean at its mouth in Connecticut. In the 1800s and early 1900s this river, like others, was a dumping ground for industry and sewage, and people avoided the unsightly view; dams were built to generate power, diminishing the animal and fish populations. In fact, the Connecticut River was once described as “the most beautiful sewer in America.” Now it is being restored, at considerable expense, as a healthful source of beauty for those who live near or visit.

Around 30,000–12,000 years ago human ancestors crossed the Bering Strait onto the North American continent (although stone tools found in the Southwest suggest much earlier human inhabitation).6 Small bands of Paleo-Indians arrived in the Champlain bioregion around 11,000 years ago, hunting in a still glacial environment. In a mere fifty years, the giant woolly mammoths became extinct, most likely due to overhunting and climatic change. Eventually, giant buffalo and woodland caribou were hunted in hardwood forests; plus walruses, seals, and whales in the new Champlain Sea. Through the years native peoples went from small nomadic bands to hunters and gatherers with specific territories and seasonal migrations, followed by a gradual shift to farming with the domestication of plants and animals. Artifacts can be found throughout the bioregion, detailing different periods. During the Woodland era (3000–400 ya) there were five language families; the Abenaki tribe in the Champlain bioregion spoke Algonquian, contributing place-names such as Lake Memphremagog and the Missisquoi Rivers, which generally describe some feature of the waterways for other travelers.7

By the time the French explorer Samuel de Champlain and his men arrived by water in 1609, native peoples were well established in the area, and had coexisted with the land successfully for thousands of years. In epidemics of 1616 and 1633, 80–90 percent of the Abenaki were eradicated due to white man’s diseases (to which natives had no immunity) and from fighting (including battles with their neighboring Iroquois enemy). From the 1600s to 1776, ongoing battles, including the French and Indian War, kept European settlers away. With the French defeated in 1763, the English arrived in earnest, lured by “cheap” land and “untouched” resources. It took as little as fifty years for white settlers to overrun indigenous peoples and cut the virgin forests. European farming techniques reconfigured the landscape into fenced fields and pastures. Immigrants flocked to the region, and the remaining Abenaki “disappeared” into the culture. As recently as the 1900s, texts reported that there were “no native peoples” in Vermont, the Abenaki having merged so thoroughly into the communities; yet there are over two thousand self-proclaimed Abenaki today in Vermont and one thousand in neighboring Quebec.

The arrival of Europeans decimated animal life as well. The beaver, key to healthy drainage and water purification across the nation, was a prime target for attack; their pelts “bankrolled” early colonists, as they could be sold to Europeans for use in felt hats. Author Alice Outwater, in her fascinating book Water, describes how English entrepreneur William Pynchon was granted a monopoly on fur trade in this region. By the mid-1670s, nearly a quarter of a million beaver pelts had been shipped to London from the Connecticut River Valley alone! Felt hats made from beaver fur were worn by both sexes throughout Europe and eventually in the Americas. By 1700 even the industrious beaver was extinct along the eastern coast, at a great loss to the water drainage of the region.

By 1812, Vermont was the fastest-growing state in the union; woodlands were burned for potash and charcoal for iron mills and logged by farmers clearing land for sheep farming. By the 1840s, Vermont was 20 percent forest and 80 percent cleared, and the state was an ecological disaster—erosion had depleted the soil, and all large mammals were locally extinct, including whitetail deer, beaver, catamounts, bear, caribou, elk, mountain lions, timber wolves, and wolverine. After the Civil War, in 1865, Vermont became the slowest-growing state in the country. Whole communities of men who had gone to the war never returned. Homesteads near the Canadian border were farmed by French Canadians who came in to tend the farms. The underground railroad once had way stations in Vermont and Maine en route to Canada, but only a few African Americans settled in this region after emancipation. Indeed, the end of the Civil War marked the beginning of the migration westward and the resulting displacement of native peoples.8

Sculptor Isamu Noguchi reminds us, “We are nature too.”

As communities of hill farmers headed out for the newly opened Midwest, they abandoned depleted farms, leaving cellar holes and stone fences as markers. This exodus marked the slow renewal of the Vermont bioregion. Hardwood forests grew again in abandoned fields, and in the early 1900s a second cutting occurred, followed again by reforestation. Today, Vermont is 80 percent forest and 20 percent cleared, with a mixed northern hardwood forest containing sugar maples, oak, spruce, fir, beech, red and white pine, butternut, hemlock, and white birch. The bioregion offers an example of recovery, along with the memory of land—plants, animals, soil, water, and people—desecrated by careless stewardship.

Wildlife has returned. In fall and spring, migrations of hundreds of thousands of snow geese stop to feed and rest on their north-south journey. Although the passenger pigeon, once present in such large flocks, is now totally extinct, other birds have returned: wild turkeys, peregrine falcons, eagles, osprey. As you walk through the woods, you might encounter a moose, bobcat, whitetail deer, coyote, or fisher; it is even possible to imagine a catamount or wolf venturing down from Quebec. Stone fences, arrowheads, and glacial erratics evoke earlier stories of the land.

Humans are part of the landscape, contributing to biological exchange. Within the narrow span of time that Europeans and immigrants from all over the earth have settled on this North American continent, each bioregion and the continent as a whole have been altered. Humans now inhabit the terrain on a large scale, as visitors or residents. It is time to understand ourselves as co-inhabitants with the land and learn to tell the bioregional stories of the places we call home.

TO DO

Place scan20 minutes

Seated or lying in a comfortable position, eyes open:

• Bring your attention to soil and rock. Where is there soil in this room or place? Use what you can see and what you know, engaging extended proprioception. If you are indoors, take time to consider the possibilities within this place and nearby, considering metals, glass, sand, and rock. Be sure to include your own body and other humans.

• Bring your attention to air. Where is there air in this room or place? What can you smell, taste, feel, hear, or see concerning air? Remember, the air is a medium of travel for birds, insects, the spores of plants, chemicals, sound waves, light waves, and humans. Consider what is happening with the seasons and with the sun and moon. Bring your attention to any aspect of air that you can perceive at this moment in time, in this unique place and season.

• Bring your attention to water. Where is there water in this room or place? Consider what’s happening with the water cycle, the water table, in the watershed for your region. Remember your body is mostly water.

• Bring your attention to animals, our relatives on this earth. Where are animals in the place? Notice the season, the effects on animals; the food you have eaten being digested in your stomach, insects and tiny microorganisms.

• Shift your attention to plants. Where are plants visible in this room or place? Even if there are no plants in sight, the floors may be wood, plants are being digested in your stomach; we wear plant fibers. Notice or imagine trees, grass, and plants of the season, contributing to the oxygen sustaining your life.

• Pause in open attention. Try scanning, eyes closed, with senses heightened.

Harley. Photograph by Leight Johnson.

Telling your place story10–20 minutes

Seated or standing in a comfortable position, eyes open (alone or with a partner):