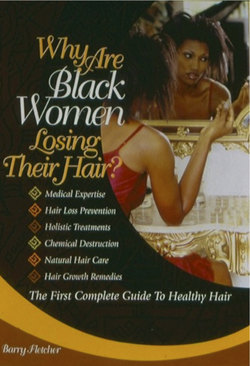

Читать книгу Why Are Black Women Losing Their Hair - Barry Fletcher - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction Barry L. Fletcher, World Class Hair Designer Mitchellville, MD

ОглавлениеI have spent my entire adult life in the hair business; training, studying, lecturing, styling, and kutting (the letter ‘c’ in cut will be replaced by the letter ‘k’, exemplifying my new Y2K Kut. See Chapter 20, “Hair 2000 and Beyond”). I have traveled the world, represented my country in the Hair Olympics, and spruced up celebrities from Tina Turner to Halle Berry to Maya Angelou. But after 21 years of mostly lauding the virtues of my industry, I’ve reached a disturbing conclusion: The industry is destroying black women’s hair. That’s right! Too many sisters are unwittingly victims of harmful products, drawn in by misleading advertisements that promise gold and deliver sand. These days I find myself doing more corrective work than creative work in the salon and that is truly distressing.

This book, like no other, will share tips and secrets about how black women can keep their hair healthy. It is a book designed to empower sisters, to give them a more complex understanding of their hair and its historical roots. With that knowledge, sisters will be better armed to maintain their manes between salon visits or eliminating those visits altogether. By the time you have finished this book, you will know the do’s and don’ts of grooming and the deleterious effects of certain services commonly provided in salons across the country.

But First, Some Perspective.

Pull out your old family albums and look closely at your mother's hair when she was young, or your grandmother's, or Great-grandmother's. You probably will notice that they had long, full-textured hair. In the early 1900s, sisters had, on average, 10 to 12 inches of hair, a length maintained through the first half of the 20th century. The main reason: Sisters didn't do much to their hair then but let it grow.

Over time, however, styles evolved, from plaiting to pressing, from naturals to curl perms, from relaxing to braiding, to weaving to locking. But here is the bad news: Today, sisters have an average length of four to six inches of hair. The truth is sisters don't learn of the impact of altering their hair until they try it. Then it may be too late.

Who is going to tell them? Not the fashion and beauty magazines, which rely on $45,000 a page ads from hair care manufacturers. And you know the manufacturers are not going to offer consumer tips that might jeopardize their profits. The hope is that hair stylists would be responsible enough to inform black women of the pitfalls of experimenting with certain styles and chemicals. But that is not always the case.

African Americans spend nearly $5 billion a year on hair products and services, but in no other period in history has black hair been as badly abused as it is today. White-owned companies are leading the charge. They have launched some of the worst products for black women on the market today: the no-lye and gel relaxer kits, the Rio products, the permanent colors and the high-alkaline shampoos. I wish I could say this bamboozlement was confined to white companies. It could be easier to attack that way. But sadly, I can't. Unfortunately, some black hair care companies are culprits too, mimicking their white brethren all the way to the bank.

Fearful of losing a sizable portion of their market to bigger corporations, these black companies are losing their integrity and selling their souls in the process. And that's too bad.

The black beauty industry has a noble history. Hair is the only business in the United States in which our presence is felt at every level. We have black schools, manufacturers, distributors, salons and barbershops servicing the black community. The black hair care industry should be a model of economic empowerment. But the tragic reality is that we have lost some of our edge and ingenuity, and we have become too greedy. Black women are complaining like mad about damage to their hair and scalp, but our researchers and scientists are not developing new remedies. Our schools cannot take eager students fast enough, but they are unwilling to pay good teachers what they deserve. Our manufacturers seem more interested in the quantity of their sales than in the quality of their products. And now that African Americans have lost their grip on the distribution side of the business, most consumers head to their neighborhood beauty supply store, where they can buy all kinds of junk. In some respect, the beauty supply store has turned into a chemical waste dump.

Remember 15 years ago when manufacturers would travel from city to city giving mini-tutorials on their wares. They would break down the chemistry of their products and teach stylists how and when to apply them. Companies wanted to make sure their products were not just sold, but administered properly.

But today, most beauty school graduates don't know how to professionally process a relaxer, press-and-curl, or use permanent color. And most state boards don't even require students to demonstrate these services to become licensed.

So Where Are We?

We are at a defining moment. Those of us who have given our lives to the beautification of black women can no longer afford to be simply stylers of hair and hustlers of products. We must be full-service cosmetologists, incorporating the principles of health and wellness into our practices. We must be, in some respect, image consultants, therapists and hair revolutionaries.

This book serves as a guide for consumers and professionals alike. It contains step-by-step instructions on how to care for every type of African American hair. There are self-diagnosing charts, cures for hair ills, holistic ideas, chemical explanations and natural methodology. The book includes essays and advice from an array of vantage points - dermatologists, psychologists, journalists, chemists and hairdressers. I know that my clients and associates want answers. So this is the beginning.

We have come a long way in hair care since the days of slavery, when butter was used as a conditioner and axle grease was used to dye away gray. When African slaves were brought to America, they were not allowed to groom themselves, and many came to view their matted, unruly, natural styles as hair in need of altering.

In most cases, the longer societal ramifications of hair have left us ambivalent. We keep suffering through an African heritage searching for a cure. Those sisters who are frequently flying from Africa to Europe on their very own hairplane should read on and find out how to qualify for a round-trip.

Today, the mosaic of black hairstyles is represented in public life, from Oprah's silky-straight relaxed hair, to Lauryn Hill's locks, to Susan Taylor's glorious braids. Our hair is as rich as the culture from which it emanates. Let's celebrate and protect it.