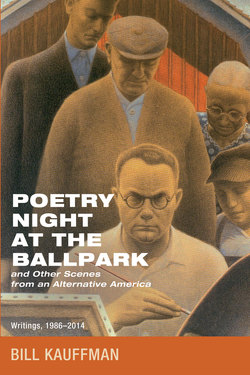

Читать книгу Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America - Bill Kauffman - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Wilson’s Picket

ОглавлениеThe American Conservative, 2011

Edmund Wilson was so securely American that he didn’t bother with vapid assertions that he lived in a “free country.” Instead, he acted as if he lived in such a place and as if the proper course for an independent insubordinate American writer was to walk his own path, no matter how poorly marked or overgrown, and then write up his journey. That is why this exemplary American man of letters spent his final years as an exile at home.

In 1962, a year into the observance of the Civil War centennial, Wilson published his magnum opus, Patriotic Gore, a massive study of the literature and litterateurs of what Gore Vidal has called the “the great single tragic event that continues to give resonance to our republic.” Wilson’s title, taken from “Maryland, My Maryland”—“The despot’s heel is on thy shore. . . . Avenge the patriotic gore that flecked the streets of Baltimore”—promised something other than Bruce Catton.

Patriotic Gore is best known for two things: Wilson’s witticism that “the cruelest thing that has happened to Lincoln since he was shot has been to fall into the hands of Carl Sandburg” and the book’s twenty-four-page introduction, a bracingly (and brazenly) dyspeptic essay that compares national governments to “sea slugs” in their mindless aggression—though unlike the slugs, nations have publicists who weave elaborate moral defenses of their violence and voracity. Wilson assesses every American war since James K. Polk’s Mexican adventure and tallies the cumulative cost: “staggering taxes,” the “persecution of non-conformist political opinion,” an “extensive secret police,” and “huge government bureaucracies.”

Wilson groups Lincoln with Bismarck and Lenin as “uncompromising dictator[s]” who “established a strong central government over hitherto loosely coordinated peoples.” Yet Wilson, who recognizes Lincoln’s “magnanimity” and acute intelligence, is no Confederate apologist. As a good Yorker from the cradle of abolitionism, he understands that “what [the South] fought for was really slavery” and that too many Southern Democrats were expansionists who would have annexed half the Western Hemisphere if given the chance.

His favorite Confederate is Vice President Alexander Stephens, the indomitable invalid Georgian whose opposition to conscription and defense of habeas corpus vexed the centralizers of the CSA.

Wilson explained to his friend and admirer Robert Penn Warren that the introduction was his attempt to “remove [the war] from the old melodramatic plane and consider it from the point of view of an anti-war morality.” But “anti-war morality” had been driven into a Mennonite-radical Catholic ghetto in the age of Robert McNamara.

Wilson’s introduction is one of the great libertarian statements in American letters, which is why the minie balls flew upon publication. The editors of the ironically named Life denounced Wilson for his “crotchety hogwash.” American Heritage refused to run a favorable notice by Daniel Aaron. No wonder, for the introduction expressed “the disillusion of a populist radical . . . the scorn of a Tory anarchist and aristocrat of the mind for the rainbow slogans of American foreign policy,” in George Steiner’s estimation.

Arthur Schlesinger tried to talk Wilson into junking the introduction, which he attributed to Wilson’s “inbred, robust isolationism.” (How robust? Asked why he disliked the British, Wilson replied, “Because of the American Revolution.” Forget, hell.)

“The disaffection of [Upstate] New York toward the Civil War . . . is behind my own attitude,” explained Wilson. He was a proprietary patriot. The country belonged to him—he was an American, dammit, and he would not be bullied by hall monitors or lectured by jingoes.

Wilson followed Patriotic Gore with the saturnine polemic The Cold War and the Income Tax. (He was against both.) These books, along with Apologies to the Iroquois and Upstate, mark the magnificent roar of a patriot of the old republic protesting the ruin of his beloved country. Thematically, they are of a piece. For instance, he compares Secretary of State Seward to the satanic Robert Moses, enemy of the Iroquois, who repellently boasted, “I can take your house away from you and arrest you for trespassing if you try to go back to it.” Sick simpering tyrants indeed.

Edmund Wilson ended The Cold War and the Income Tax with a plangent confession: “I have finally come to feel that this country, whether or not I continue to live in it, is no longer any place for me.” The nation’s most distinguished literary critic was a stranger at home because, as a good American, he detested militarism and cant.

“Whenever we engage in a war or move in on some other country, it is always to liberate somebody,” wrote Edmund Wilson fifty years ago. He could have written it yesterday.